Wed 9 Jul 2014

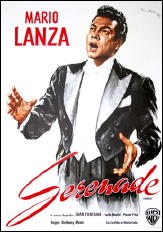

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: SERENADE (1956).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews[9] Comments

SERENADE. (1956) Mario Lanza, Joan Fontaine, Vincent Price, Sarita Monteil, Vince Edwards, Harry Bellaver, Joseph Calleia. Screenplay Ivan Goff, Ben Roberts & John Twist, based on the novel by James M. Cain. Directed by Anthony Mann.

After a four year hiatus, this was to have been Mario Lanza’s triumphant return to the screen.

As such it’s hardly a triumph.

Serenade is James M. Cain’s finest book according to most critics, and his biographer Roy Hoopes, and for once I agree. It’s a dark symbolic journey through hell to a kind of redemption complete with a Christ-like sacrifice. It tackles big themes, and for its time is quite blatant about the heroes bi-sexuality, and his reclamation of his manhood (Cain’s theme, not mine, so go after him if you must) thanks to Juana, an earthmother-like Mexican prostitute.

The hero of the novel is a gifted singer who threw away his talent on pop music, thanks to his Svengali-like impresario and lover. On the skids, he has gone south to Mexico where he meets Juana, a woman he once had a passionate affair with, and after a death, they go on the run.

Heavy on symbolism, the scene where the hero and Juana make love in the abandoned church, the sharks and the iguanas are all justly well remembered elements of the novel, and the hero’s plight becomes a metaphor for the corruption of modern society. Though readers here might prefer The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce, or Love’s Lovely Counterfeit, this is Cain’s greatest achievement as a novelist.

The movie, not so much. Imagine trying to make a musical and woman’s picture of Under the Volcano or Day of the Locust, and that might be easier than this book.

We open with Mario Lanza being discovered in the California vineyards. Under the guidance of beautiful but cruel Kendal Hale (Joan Fontaine) he loses his voice and flees her to Mexico where he meets young beautiful, rich, and passionate Juana Montes (Sarita Monteil). She is attractive, but hardly any of those other things Juana represents in the novel, and the scene where she dresses like a matador at a party and battles a mock bull is supposed to mirror a scene in the book, but instead plays like bad comedy.

After the fourth musical number in the first twenty minutes, and following the awful title number by the usually great Sammy Cahn, you know this film has abandoned Cain for standard women’s picture country. That might have worked in Douglas Sirk’s hands, but this is clearly not a comfort zone for director Anthony Mann and screenwriters Goff, Roberts, and Twist.

Vincent Price is good as Lanza’s friend and ally, but all you can think of watching him, is what he might have done as the controlling homosexual impresario.

Granted, you couldn’t film Cain’s novel without a great deal of obfuscation at that time in Hollywood, but it didn’t have to be turned into this big Technicolor turkey either. A good noirish black and white film is lurking beneath this clown show.

The novel is a blend of Hemingway, Graham Greene, and Christopher Isherwood in Cain’s own unique voice. It is full of memorable scenes, imagery that will stick in your mind, dark under currents tugging like riptides at unwary readers, and the restoration of the hero’s voice becomes a metaphor for his soul and his manhood.

In the film the attractive Sarita Monteil couldn’t redeem Green Stamps, lives in a palatial ranchero William Randolph Hearst might envy, and it’s hard to believe she and Lanza like each other, much less become so indelibly tied that she virtually becomes his lost soul.

Fontaine and Price try hard, but there is nothing here to work with. Mann does nothing that remotely resembles Anthony Mann, and the story plays as if it was written from Cliff Notes of the novel or the Classics Illustrated version.

This is bad soap opera and a mediocre musical, with a star who returns to the screen fat and unconvincing. He isn’t bad, but at most he seems peeved rather than tortured by his lost voice and by implication masculinity. I’ve displayed more angst when I mislaid the car keys.

The novel is dark, sensual, powerful, shocking, blatantly sexual, violent, noirish, and symbolic. It has the quality of a nightmare, but there is no awakening, only an ironic sort of redemption out of sacrifice and tragedy.

Serenade the film is tired, trite, empty, slick, pointless, and disappointing. It did nothing to rebuild Lanza’s fading career, and stands as a black mark against Anthony Mann.

The problem is that Serenade is exactly the movie you would expect Hollywood to make of Cain’s novel in the nineteen fifties. It is so what you would expect you could do a better satirical film about how Hollywood corrupts this kind of book. It is far and away Cain’s least film adaptation, and a sad fate for a stunning novel.

The music is bad and Lanza fat, so his fans have no reason to watch it; the film is flat and unimaginatively shot so Mann fans have no reason to watch it even as completists. There is no redeeming performance by anyone who hasn’t been better elsewhere, the script is dull, and even Mexico doesn’t look that good in widescreen Technicolor.

Read the book then rent Double Indemnity if you need a dose of James M. Cain’s unique perspective.

July 10th, 2014 at 4:11 pm

I have to say, as a general rule, I tend to enjoy films noir or films based on noir books/stories that have Vincent Price in them. This seems to be a film that would be an exception that would prove that rule.

I should probably read the Cain book. I confess I haven’t. Seems like an important work and I appreciated your summary of it.

July 10th, 2014 at 4:56 pm

I’ve never seen the movie and I’m sure I never will. I have read the book, and even though it was almost 60 years ago, there are some scenes that I still remember.

Time to read it again!

July 10th, 2014 at 5:55 pm

Jonathan, Steve

This book is critical to an understanding of Cain’s milieu, and while it is not a crime novel per se, it is easily his darkest book and most powerful. This is the book you need to read to take Cain seriously as a novelist. I’m sure there are many readers who found it too heavy, or too far from what they expected, but it stands on its own, well away from Cain’s other works, and even for Cain who was known to be ‘racy’ this dark book was shocking in its time.

And like you, Steve, there are images that linger decades after the first reading. The seduction in the old chapel is fully as sensual and memorable as Hemingway’s ‘the earth moved’ scene in For Whom the Bell Tolls, and less metaphorical.

Read it, and you will never look the same way at an iguana again.

July 10th, 2014 at 9:38 pm

In her study of Anthony Mann, film historian Jeanine Basinger (Wesleyan University — my alma mater, in fact) writes as follows: “What’s remarkable about Mann’s career is importantly illustrated by the unimportance of Serenade: it is really the only film he ever made in which his directorial presence cannot be fully felt.”

July 10th, 2014 at 10:00 pm

I don’t what it means, if anything, but Anthony Mann and Sarita Montiel were married for several years, 1957-1963.

July 11th, 2014 at 12:28 am

I looked at my copy of the book, which is the Penguin Books paperback edition of February 1947 with the distinctive Robert Jonas symbolic cover.

My note shows that I read the novel in January 1982 and liked it. My comments say in part, “Very unusual plot–a bi-sexual opera singer falls in love with a Mexican prostitute, plus he’s a tough guy!”

I intend to read this again, maybe tomorrow.

July 11th, 2014 at 4:15 am

I have various editions of this book in my music-and-crime book collection. I found the novel very interesting when I read it, but I prefer Cain’s “The Postman Always Rings Twice”.

July 12th, 2014 at 12:07 pm

I finished rereading SERENADE today and it held up nicely to a second reading. Outstanding and if you love opera music, then you will enjoy the background details of the opera business and art.

February 24th, 2022 at 9:54 pm

[…] reviewed here by Max Allen Collins. The film panned here by David […]