Sun 18 Oct 2015

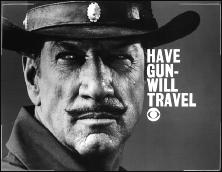

A Western TV Review by David Vineyard: HAVE GUN – WILL TRAVEL “The Gladiators” (1960).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV Westerns[9] Comments

“The Gladiators.†An episode of Have Gun – Will Travel, 19 March 1960. (Season 3, Episode 27.) Richard Boone. Guest Stars: Paul Cavanaugh, Dolores Donlon and James Coburn as Bill Sledge. Teleplay: Robert C. Dennis. Series created by Herb Maddow and Sam Rolfe. Directed by Alvin Ganzer.

Have Gun – Will Travel was seldom just an ordinary western, and on occasion barely a western at all, as in this episode which opens in San Francisco at our hero Paladin’s (Richard Boone) rooms in the Carleton Hotel where he is receiving an attractive young lady, Miss Alison Windrom (Dolores Donlon) of New Orleans, with seduction on his mind, as evidenced by the champagne that accompanies her to the room and his lounging jacket.

Alas for our tarnished knight, Miss Windrom is concerned for poor Daddy back home (veteran actor Paul Cavanaugh), who has accepted a challenge to a duel:

“He’s a very proud man, Mr. Paladin, he’d rather die than yield.â€

“Is that a family trait?â€

It is the nineteen-fifties, and we know the seduction is not going to succeed, but the teleplay and Boone’s delivery of the lines makes no bones about what Paladin has in mind. It isn’t surprising audiences were ready for the much more successful James Bond a few years later. All this unfulfilled seduction and innuendo had to end at some point in a bedroom somewhere.

Of course once he is hired, Paladin is all business. In that he, and most of the gunslingers in Westerns, very much resemble the work ethic of the private eye of pulp fiction, all business, no matter how attractive the distractions. In many ways Paladin is a private eye as much as a hired gun, though he is seldom cast in the role of detective.

Over the course of the series we learn little of him other than he is an ex-soldier, fast with a gun, would rather talk than fight when possible, has exquisite tastes acquired if not born to, is possessed of a mordant and quick wit, and is cynical but still a romantic despite his jaundiced eye.

He would like to be wrong about people and is gratified when he finds one of the few who defy is dark assessment of humanity. He is a man out of his time and place who probably would only really fit in San Francisco of that era or as an Elizabethan privateer. He is very much Chandler’s errant knight ‘good enough for any world,’ but his mean streets are most often dusty trails ending in a showdown.

Miss Windrom is convinced the other party in the duel, the younger Mr. Beckley (George Neise) will step out if Paladin shows up as a proxy for her father. So Paladin gets dragged into it, protesting all the way, and steps into the looking glass with the Southern aristocrats who would rather die than yield, even if it means over the bodies of innocents.

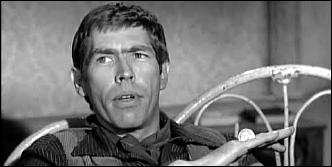

Or not so innocents, when Beckley hires his own proxy in the person of gunfighter Bill Sledge (James Coburn) from Texas, a man with a reputation with a gun equal to Paladin. The two men know of each other, and they meet on neutral ground with mutual respect for the other’s skill and professionalism. That paean to professionalism is also a throwback to the classic private eye of Hammett who is redeemed more by that trait than his humanity, the Code of the West is ironically largely the Puritan work ethic.

Paladin considers the duel nonsense, and so does the dark but charming Sledge. Neither particularly wants to kill anyone, certainly not for two arrogant fools battling over some obscure point of honor, and it seems for a moment like the meeting on the field of honor and blood can be avoided if Paladin and Sledge refuse to fight, but Sledge can’t help but wonder which of them would win, and …

Sledge: I never done much of this kind of fighting in Texas. Hear tell there’s rules.

Paladin: You pay much attention to rules?

Sledge: Never done yet.

This episode is a tight little psychological game, as Paladin finds himself Alice surrounded by White Rabbits and Mad Hatters obsessed by ‘honor’ and inured to death. He finds the price of honor in this case too high, but no one else does, and as the tight little half hour goes on he inevitably will find himself on that field of honor and blood at dawn.

· Paladin: “How much blood will you settle for?â€

The episode may surprise some who have a certain view of series drama from the Fifties. It is bitter, cynical, downbeat, dark, and unforgiving. That the conclusion is predetermined and unavoidable from the first makes it all the worse. It has the sharp taste of bitters without the gin, a nasty dose of quinine made palatable by watching two outstanding actors, both gifted at playing villain and complex hero, both with charm and cool to spare (had this episode also included those two other masters of small screen cool, Steve McQueen and Robert Culp, it could have frozen and shattered television tubes) in acutely observed and written roles clearly enjoying themselves.

Coburn displays the vicious charm that worked equally well as dark hero or psychotic villain and would soon lead him to stardom, and Boone, who has the same qualities on screen, seems to enjoy his scenes with him, recognizing an equal. That, and the sharp observation of a world where honor encompasses wagering on death and wasting lives over obscure points make this episode a standout as Paladin learns the savagery of the “savage land†of the series theme song is nothing compared to that of the civilized world.

Have Gun – Will Travel was always a well-written series, and thanks to Boone, always well-acted, but this one is a standout, a cynical little gem about the cost of violence and cultures that embrace it.

It is also rare in that Paladin, the man who holds himself above the rest, is as compelled by his own code of honor as the men he condemns to see it out to the end, and in the final scene he is as disgusted with himself as them. This episode comes close to tragedy since no one in it escapes their hubris or pride whether they live or die.

In the end, Paladin is a victim of his own honor as much as they are and bloodied by it as surely. His slight rebuff of all that has gone before in the final scene, when he throws a glass of champagne to the ground with a bitter comment and stalks off as the screen fades to black, isn’t satisfying for the character or for the viewer, and perhaps all the darker because we as voyeurs wanted to know which man would prevail as well.

For a half-hour episode of series television from that time period “The Gladiators” bears a great deal of existential despair, especially for a Western. Even for a series as quirky and adult as Have Gun – Will Travel, this episode is savage and dark.

October 18th, 2015 at 10:18 pm

Two of my favorite TV writers wrote for this series. Sam Rolfe created it and produced the first season until problems with the star drove him away. Rolfe had also wrote the radio version as well.

There is a story of Boone getting into a fist fight with one of his producers. It was not usually for tough ex-fighter types to work in the world of early TV and Rolfe had been an ex-boxer. Whoever it was I hope he hit Boone hard. You try to write to please the highbrow NY critics when you had over thirty episodes to do a season and no budget. I hope Boone learned to be nicer to his writers when he did THE RICHARD BOONE SHOW.

My other favorite writer involved here was Robert C. Dennis. He had a habit of writing my favorite episode of whatever series he worked for. His scripts often had a wit or weird off-beat quality to them but he could also go dark as well. I know very little about him but here is his NY Times obit

http://www.nytimes.com/1983/09/17/obituaries/robert-c-dennis.html

October 18th, 2015 at 11:13 pm

It’s ironic that the way the happy ending is ingrained in series television and major films today that early television with all its restrictions often went darker and more existential than what is now available. Series like GUNSMOKE or HAVE GUN – WILL TRAVEL that we think of as family value series often went dark in ways that would be barely acceptable today or at least draw fire.

Paladin is a playboy, would rather drink and gamble and womanize than work, and while he is inherently noble there is also a streak of violence in him and his reluctance to kill is at best a feeble protest. It is hard to imagine how he would make money if killing were not an option.

But this episode, which I first saw back as a child, and which stayed with me all these years, is a good illustration of what could be done in a half hour format. I can’t see that another twenty minutes would have added anything to the proceedings. The best half hour dramas had the quality of a good short story in that the telling was succinct and to the point.

I still hold the loss of the half hour television drama was bad for the medium, though today in real terms that would mean sixteen minutes of storytelling time(most hour long episodes are actually less than forty minutes of material and feel padded at that)which is too short.

Boone was famously difficult, and yet the result was worth it so if it cost him a punch in the face it was worth it. I would rather see an actor fight for good material than accept whatever he was handed which also happened with series. A happy set isn’t always a productive one as John Ford films demonstrate — he was notoriously hard on actors.

There is a famous clip shown on TCM of Andre de Toth calling Hitchcock a son of a bitch for calling actors cattle, and yet I can’t imagine an actor who would seriously claim he would rather have been in a de Toth film (good as many were) than a Hitchcock one (well, maybe Randolph Scott). Preminger and Fritz Lang were also notoriously hard to work for. In fact Howard Hawks seems to have been a rarity as a director most actors enjoyed working with who also was an auteur.

Sometimes it takes difficult people to create art, if Boone was difficult I would have to say it often paid off on screen. Nice can be overrated, the whole point of Minnelli’s brilliant THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL.

October 19th, 2015 at 12:03 am

Dick Powell proved you could produced quality programs without killing the crew and writers.

It is fun to see how TV has changed over the decades. In the beginning advertisers ruled, then the stars began to take over. Powell is one of the few from the 50s and 60s people loved to work for. The list of demanding stars is endless including Sid Caesar, Lucy, Jack Webb, Red Buttons, Red Skelton, Steve McQueen, Peter Falk, and on and on. It was not always about getting better but tending to a fragile ego.

Today with the larger cast and less stars the writers have become actual showrunners. The exception is with major free network shows where the network suits rule with an iron fist (why most of the best talent works for cable networks).

Every decade had its quality programs. HAVE GUN WILL TRAVEL was one of the best in its time. But the earlier episode were the best, the more hard Boone became to work for the less top writers/producers wanted to deal with the series.

October 19th, 2015 at 12:40 am

Speaking of Robert Dennis, I was driving north from Portland, OR, one day when I picked up a young lady who was hitchhiking. We chatted, and I mentioned I read mysteries. She said her father wrote some, and also wrote for TV shows, including DRAGNET. So there I was with Lisa Dennis and the two hours to my town flew by. I wish there was more to tell but we parted by a freeway on ramp and I hope she made it to grandma’s house.

October 19th, 2015 at 2:07 am

Circa 1973, Robert C. Dennis published a pair of original novels, The Sweat Of Fear and Conversations With A Corpse, published by Bobbs-Merrill.

These books featured Paul Reeder, a psychic detective. Reviews were mainly favorable, but the prospective series stopped at two.

Here’s the jacket bio:

“The Sweat Of Fear is Robert Dennis’s first novel, but he has been in the writing game for many years as a TV scripter. Think of any popular show and he has had a hand in it: Cannon, Mod Squad, Mission: Impossible, Perry Mason, Twelve O’Clock High, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, plus twenty-five other series just as popular. As would be expected, he lives and works in Hollywood.”

Over at Bare Bones E-zine , Jack Seabrook is working his way through the Hitchcock TV series by writers.

Jack is currently seven shows into Robert Dennis; at his regular rate he should go well into next year.

Robert C. Dennis died in 1983, ten years after he wrote his novels.

It’s too bad he didn’t live long enough to do promos for MeTV; his credit turns up on so many of their shows.

October 19th, 2015 at 3:31 am

I watch HG-WT a lot in reruns, and you’re quite right about the skillful use of the half-hour format. I also note that some of Gene Roddenberry’s scripts for the show feature story elements that would reappear on START TREK.

October 19th, 2015 at 11:46 am

4. Cap’n Bob, thanks for the story. I lived in Hollywood for over twenty years and I have stories like that where you meet some one only to later realize who they were.

5. Mike, thanks for the info. Now I have two more books to add to my find and read bucket list.

October 19th, 2015 at 2:19 pm

Michael,

My favorite story of accidentally meeting someone you admired happened to Frank Gruber who wrote about being in a second hand book store with his son and while he was checking the shelves his son was talking to an older man sitting in the store — who turned out to be H. Bedford Jones. I ran into Kirby Grant (Sky King) in a haberdashery on the square in Denton, Texas that was owned by a former tailor for Republic Studios who still made clothes for some of the former stars. Six weeks later I ran into Duncan Renaldo in the same store who had flown in for a fitting.

Re bad behavior.

By nature actors have fragile egos and often behave that way, as do producers and directors as well as choreographers and almost any talent. Writers do as well, but no one much cares because of the lack of power. The episode in question here is from late in series three so obviously talent stayed with the show.

In most cases the writers don’t have a lot of contact with actors anyway. It isn’t as if they are on the set during filming most of the time. Producers and directors tend to take much of the flak from actors over scripts unless the actor is also a producer and even then only the top writers can afford to be picky about who they work for.

I would only add that most of those difficult actors and stars mentioned produced some of the best television of the golden age. That isn’t to say that nice guys didn’t produce great work as well, they did, but art and entertainment doesn’t much care whether it is produced by nice people or not. Dick Powell is certainly one of the nice people who managed to succeed, but then he directed, starred, and produced and for all I know wrote so he had horses in all ends of production. On a show like HG – WT the show was Boone.

He carried it alone with little support, every episode dependent on his performance and his screen persona. I’m not defending bad behavior, but over all the result was first rate and I don’t question that either. Art is illusion anyway. Almost the entire run of MARCUS WELBY was written around the fact of Robert Young’s alcoholism, but I can’t say it ever shows on screen. The fact Boone was difficult doesn’t show on screen either.

Art doesn’t always come from order and happiness, sometimes it comes from chaos and emotions. It would be nice if art was only created by nice people, but it never has been.

October 19th, 2015 at 2:58 pm

David, HAVE GUN WILL TRAVEL lasted six seasons. I was referring to the fifth and sixth seasons.

For some great behind the scene stories from those who where there I recommend Kliph Nesteroff’s blog Classic Television Showcase. Has nothing to do with Richard Boone but lots of great stuff about comedy TV of the era.

I worked for AMC Century City movie theatre as a customer host. There I answered questions about the movies playing and escorted stars into the theatre. Two of my heroes, Mel Brooks and Sean Connery called me by name. I have small stories about people such as Dustin Hoffman, Robert Culp, Oliver Stone and others. I wish I had been sharper when talking to Dennis Hopper about BACKTRACK (with Jodie Foster). But my biggest regret was when I met Burt Lancaster. At the time I knew him more for his grinning action hero persona. Shortly later I saw SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS. There was so much more I would have talked to him about if I had been aware of that side.