Fri 27 Aug 2010

Reviewed by William F. Deeck: ELSIE N. WRIGHT – Strange Murders at Greystones.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[7] Comments

William F. Deeck

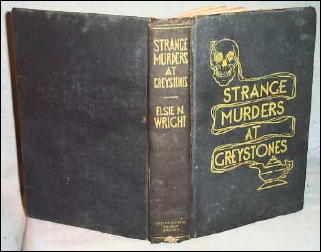

ELSIE N. WRIGHT – Strange Murders at Greystones. International Fiction Library, US, hardcover, 1931.

As Holmes has warned us, it is unwise to theorize without facts. Nevertheless, I am tempted to speculate that someone, either an enemy or a practical joker, told Wright she should write a book.

That same someone may also have suggested to International Fiction Library that it should publish a book regardless of merit. Unfortunately, the twain met.

Of course, it’s possible the typesetter had a hand in the confusion. The many typos, particularly the missing and misplaced quotation marks, provide some confirmation of this hypothesis.

Perhaps the typesetter forgot to include a few of the manuscript pages, thus leading to at least this reader’s confusion.

Anyhow, Thatcher Graham, master of Greystokes and an absolute rotter, is found dead in his library with the back of his head bashed in. Apparently, let me hasten to say; this, as well as other alleged facts presented by the author, is not definite.

Inspector Kelley comes to investigate. Kelley, the author tells us, is a keen and intelligent detective who has worked his way up the ranks. As portrayed, however, he is an utter buffoon who solves most of his cases by beating confessions out of suspected crooks and browbeating witnesses.

His working principle is that anyone with an alibi is probably guilty — why else have need for an alibi? — and anyone without an alibi is patently guilty.

Arresting the fiancé of Graham’s daughter is the only wise move Kelley makes. Dumb as he is, he almost had to do it. But then Sergeant Brock, who has been left in the house for no particular reason except the author’s need, is killed, somehow, by a creature with “piercing green eyes.”

The police are called again, they arrive, they search the grounds, they depart. What about Brock’s death? Oh, it’s mentioned a few pages later that the police are upset about Brock’s being killed, but that’s it.

Our hero, Jack Pelton, whom Kelley still suspects even after Brock’s death, gets out of jail. Arriving at Greystones, he and his fiancee, Polly, go out to search the grounds. Polly says that the police already have done so. Jack says they didn’t know what they were looking for but he does. What is it? Neither he nor the author says; indeed, no search is made of the grounds.

Jack does find a bloody dagger — by sitting on it. This weapon is important to two people, both of whom crave it. Why? After burning incense and checking chicken entrails, I must conclude that it is the only sharp instrument on the estate. There’s no other apparent reason for wanting it.

Approaching the dog kennels during their non-search of the grounds, Jack and Polly spot the green-eyed creature entering the kennels. When they go in, the creature has disappeared and there are bloodstains, which leads Polly to conclude, on no other evidence, that a dog has been killed.

Inspector Kelley comes wandering by, and they all go in to lunch, without a word being said about the creature or the dog.

A new cook is hired. Why? Apparently the author felt she needed alleged comic relief, so she introduces a black who talks about the “debbil” and “hants” and has hysterics. What happened to the other cook? Probably only the typesetter knows.

Searching subterranean tunnels with Polly, our hero notices that she is shaking badly. Bravely — oh, he’s brave but not bright — he gives her a revolver and walks in front of her. Later he fires that same revolver that she had not given back.

Inspector Kelley had provided the revolver, apparently carrying two for those occasions when he might need to give one away. The next time he comes, however, and two guns are needed, he has only one.

Kelley is also cheap, for the pistol contains but a single bullet. Our hero had examined it earlier and had no complaints, but if he’d had more than one bullet the novel might have ended too soon — that is, for the author’s and publisher’s purpose.

He discovers the single bullet when he wisely is “trying the revolver to see if it had jammed.” Later Kelley’s revolver, most unusually, does jam.

Wright is unstinting in her use of verbal and plot cliches. The word horror appears at least 50 times, she being unable to convey the real or imagined item. There are numerous “blood curdling” laughs, an idiot who utters “gutteral” — is the author or the typesetter toying with us here? — cries, trapdoors, a butler who acts strangely, a dotty housekeeper with a secret, concealed passages, and a genuine, unadulterated mad scientist with a 20-year grudge.

This is Wright’s first and only mystery. Wisely she wrote no more. What could she have done for an encore?

August 27th, 2010 at 9:01 pm

Wow, sounds like the author’s name should have been Elsie Dunn Wrong.

August 27th, 2010 at 9:54 pm

Sounds like Elsie Dunn something awful.

Though to be fair a book this bad can be great fun in the right mood.

I don’t know why people who would otherwise never consider writing a book assume they can pen a mystery, or how so many of them managed to get into print. It sometimes seems as if you only needed to put murder in the title to get published in the twenties and thirties.

August 27th, 2010 at 10:48 pm

I think Bill Deeck must have had a little fun reading this one, or he couldn’t have finished it.

He certainly had fun writing up this report afterward.

The book itself is easily available, by the way. A copy with a jacket will cost you $35, but without one, far less.

And as far as your last paragraph is concerned, David, Bill blames the typesetter. I’m not convinced, but maybe.

August 28th, 2010 at 10:54 am

I read this bad book eons ago.

This is a “mystery” by an author who doesn’t really adhere to the form. Wright will clearly never, never be asked to join the Detection Club.

November 25th, 2011 at 1:21 pm

The first mystery I ever read about 50 years ago! Found it in my parents’ basement. Loved it then (age 10).

May 28th, 2012 at 3:35 pm

My aunt by marriage, a proofreader for World Publishing, wrote this at the tender age of 20. I think she’d readily agree it was a screamer, but what a thrill it must have been for her at the time. She went on to write a number of sports & Patrol Boys books for kids later on (as well as a mystery for girls). From other potboilers I’ve read, it was a more forgiving literary period. 😉 By the way, I am a member of Mystery Writers of America & have served as an Edgars judge. I am quite proud of Aunt Elsie.

June 21st, 2014 at 1:23 pm

My Girl Scout leader Dorothy Darling of Crete, Nebr. read this to us on a camping trip in the mid thirties when we scouts were 10 or 12 years old. She made it sound so scary and fun as we sat around the campfire in the dark eating toast chocolate S’mores. I’ve been looking for the book ever since and just found it via Google. Of course, I’m disappointed with the denigrating review — some of us kids loved it.