Thu 27 Oct 2016

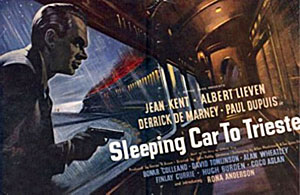

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: SLEEPING CAR TO TRIESTE. (1948).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[5] Comments

SLEEPING CAR TO TRIESTE. General Films, UK, 1948; Eagle-Lion, US, 1949. Jean Kent, Albert Leiven, Derek de Marney, Paul Dupuis, David Tomlinson, Alan Wheatley, Rona Anderson, Finlay Currie, Bonar Colleano, Zena Marshall, Grégorie Aslan, Hugh Burden. Screenplay by Allan MacKinnon from a story by Clifford Grey. Directed by John Paddy Carstairs.

An excellent spy story set on a train (and the famed Orient Express at that), a setting I can never resist, with a top notch cast, and an involving and cannily observed Ship of Fools style script and cast.

The film opens as suave adventurer Captain Zurta (Albert Leiven), in white tie and tails, robs an embassy safe in Paris during an embassy ball, cold-bloodedly kills a waiter who interrupts him, passes the diary he steals on to his associate Karl (Alan Wheatley) waiting outside, and rejoins his beautiful companion Valya (Jean Kent) to leave before they are discovered. Things start to go wrong though, when the next morning the two go to collect the diary and find Karl has double crossed them and fled to sell it on his own, catching the Simplon Orient Express (*) for Venice and Trieste (then a ‘free’ city between East and West whose very name suggested intrigue) and beyond to Zagreb and Istanbul.

The urgency of catching up with Karl, traveling as Charles Poole expatriate Englishman, is demonstrated by Zurta’s own admission: “Beyond Trieste I’m a wanted man. Beyond Trieste I am dead.â€

Zurta and Valya just catch the train and it’s Grand Hotel of passengers, one of which is their quarry.

Aboard the train is married divorce lawyer George Grant (Derek de Marney) and the innocent young women he is taking for an illicit holiday Joan Maxted (Rona Anderson); comic Englishman, and former client of Grant’s, Tom Bishop (David Tomlinson); skirt chasing American soldier Sgt. West (Bonar Colleano) and sharing his compartment a bird enthusiast who won’t shut up; a pair of beautiful French girls returning from a shopping holiday in Paris and leaving boxes of hats with all the men on the train to avoid the customs fees; train chef Poirier (Grégorie Aslan) saddled with an English son of one of the line’s board members who wants to learn to cook but thinks boiled cod and chips is a delicacy; and just Poole’s luck, the last minute companion in his compartment, Inspector Joif (Paul Dupuis) of the Paris police, hero of the resistance, and something of a French Sherlock Holmes.

That sets off the game of musical compartments as Poole tries to get a compartment by himself, briefly succeeds, hiding the diary in the new one, then finds himself ejected as famous and penurious and vain international author McBain (Finlay Currie) and his abused secretary Mills (Hugh Burden) occupy the compartment.

But they are only on the train until Trieste where Poole can get it back if he can find a place to stay away from Joif and the two hunting him, which is how he stumbles of the illicit lovers at lunch as they try to avoid the obnoxious Mr. Bishop who is a notorious gossip and determined to organize a poker game with Grant, who has other things on his mind.

And when Zurta kills Poole and frames Grant only to find the diary is missing, all the differing threads begin to come together.

Screenwriter Allan MacKinnon was not only a first class writer of film thrillers, but a top notch thriller writer in his own right (Cormorant Isle) often compared to Victor Canning and Geoffrey Household (no mean company for comparison). John Paddy Carstairs was a first class British director, and the cast, while devoid of big names save perhaps Kent, is a who’s who of top British and International character actors.

Unusually the film hasn’t really got a hero per se. Grant, as played by de Marney, is a bit of a heel all too obviously leading the girl on, and her simpering willingness to be fooled detracts from too much sympathy for her character. Bishop, played with perfect obnoxious self centered British satisfaction and obliviousness by Tomlinson (Mary Poppins Mr. Banks), will save the day, but blindly and by butting in where he isn’t wanted.

McBain finds and tries to save the diary for himself because it will harm a country that has shunned him and his secretary Mills finds it and tries to blackmail him with it, a worm who all too easily returns to worm status. Zurta is a cold blooded killer willing to sacrifice anyone along the way with no moral or political axe but his own need for adventure and money. Valya, is a little sympathetic, but only a little so and rather ruthless herself in pursuit of her ideals. As for Jolif, he is willing to hang whoever’s neck the noose fits, rather like some real Paris policemen I knew.

That is probably why this one is such a delight. There is no United Nations message of international cooperation like Berlin Express and no dashing hero and spunky heroine like The Lady Vanishes. The train is filled with flawed people, not evil, even Zurta and Valya aren’t evil, just human beings caught up in their own comical and tragic dramas thrown together in an artificial environment and rather savagely, but with British reserve and taste, dissected as pressure is applied. The American is a girl chasing vulgarian (“We are tired of being liberated,†a French Zena Marshall tells him pointedly); the Scotsman is cheap, cruel, vain, and petty; the Brits are all insular and judgmental; and the Europeans all seem bored and a bit rude.

But it is all so expertly played and written that despite that you recognize the characters as humans deserving of sympathy for all their flaws depending on their varying degrees of innocence.

Sleeping car or not, no one, certainly not the audience, gets much sleep on this trip to Trieste.

* Just a note, but I traveled on the Orient Express in the seventies, and it never looked more like just another train than here. I suppose something to do with post-war austerity in England. The gilt and red velvet (the film is in black and white, but still …) are gone; there is no sense of the gilded cigar smoking cherubs on the dining car ceiling; and the windows in the compartments only open eighteen inches, not wide like British trains of that period as shown here.

Granted the train was not its glorious self in 1948, and not fully restored until the nineties (it wasn’t really the famed Orient Express when I rode it, not exactly, still twenty years or so from the full restoration to the glory of the great years pre-WWI and between the wars), but it was still much more cosmopolitan and less British commuter train than it appears here, a small flaw in an otherwise delightful film.

October 27th, 2016 at 3:04 pm

What a review! I’ll seek it out.

October 27th, 2016 at 8:46 pm

Movies and trains, what a great combination. I was disappointed with BERLIN EXPRESS, though. Not enough train to suit me. This one sounds much much better.

October 27th, 2016 at 8:51 pm

It’s a good little movie. More or less a remake of ROME EXPRESS which is an even better movie.

October 27th, 2016 at 10:10 pm

I am sometimes very slow on the uptake. This movie was reviewed once before on this blog, and at that time by Mike Tooney. Here’s the link:

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=31717

And be sure to read the comments, too.

October 30th, 2016 at 8:55 pm

It’s a surprising film because it doesn’t really have a hero or heroine.