Sat 20 May 2017

Reviewed by William F. Deeck: JONATHAN STAGGE – The Dogs Do Bark.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[5] Comments

William F. Deeck

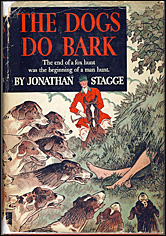

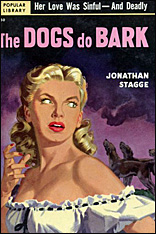

JONATHAN STAGGE – The Dogs Do Bark. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1937. Popular Library #350, paperback, 1951. Also published as Murder Gone To Earth (Joseph, UK, hardcover, 1936).

A question is often raised about whether it is worthwhile to spend time and space reviewing a poor novel. Why bother? Well, if nothing else, to warn prospective readers that they may be in for a disappointment. And a disappointment is what The Dogs Do Bark definitely is in this reviewer’s opinion.

Here ! must flout our distinguished editor’s admonition not to give anything away in a review. How else describe this book’s weaknesses?

A headless and armless female body is found during a fox hunt in Massachusetts. Since a female is missing from the area, her father, a religious fanatic, is asked to view the presumably naked torso of the corpse and identifies it, more or less, as his daughter, while throwing in some wild religious quotations to prove his fanaticism. Don’t ask me how this zealot was so familiar with his daughter’s naked body. (And the author certainly didn’t want anybody to ask.)

After the father has viewed the corpse and identified her, more or less, he is then read a description of the body, presumably another author’s ploy so that the authorities can say that she was not virgo intacta, although not pregnant, and thus must either have been married or immoral. The coroner and the doctor — the latter is the amateur detective in the novel — who had been deputized by the sheriff both seem to think that sexual intercourse is the only way that the hymen can be broken, no doubt a fond delusion during the 1930s.

Later on in the book we are told that the girl identified as the corpse thought she was pregnant. Do the doctor and the sheriff look at one another with wild or even mild surmise? Of course not. The primary reason for the head and arms being removed from the body does not occur to them, either. If it had — and some thought was given to another female’s disappearance, one who looked much like the corpse — the book would have ended at chapter 3 or 4. And what then would have become of the so-much-per-word story?

The arms are found in the hunting pack’s kennels, stripped to the bone by the dogs. The head is located later elsewhere, kept by the killer for reasons never made clear. The deputy doctor seems to have only one patient, a hypochondriac, so he has plenty of time to blunder around and nearly get himself killed in a had-I-but-known-or-even-given-it-some-thought fashion. He comes close to being burned to death in an old barn by the murderer, and it would have served him right. Once the corpse is correctly identified, a telegram from another police force points out the killer.

Recommended only to those who have a mild interest in the U.S. fox hunting scene.

Editorial Comment: I believe but I am not positive that the doctor Bill refers to in this review is Dr. Hugh Westlake, who appeared in all nine of Jonathan Stagge’s detective novels, of which this is the first. (I do not know who the deputy doctor might be.) Stagge was a pseudonym of Richard Wilson Webb, (1901-1970) & Hugh Callingham Wheeler, (1912-1987), who also collaborated on books as by Q. Patrick and Patrick Quentin.

May 20th, 2017 at 5:58 pm

The deputy doctor is in fact Dr. Hugh Westlake, Steve. He is deputized by the sheriff and that’s how he becomes an amateur sleuth in this first book in the series.

I’ll risk my reputation as a judge of excellent mystery novels in stating that Bill is unduly harsh on this debut of Wilson & WEbb as “Jonathan Stagge.” Readers familiar with the macabre themes and outrageous murders in the Stagge mysteries will probably be wiling to look the other way in terms of the lack of realism. These mysteries are not intended to reflect real life at all. They are specifically intended to shock with their gruesome details and intensely Gothic a mood all of which are mentioned in Bill’s review above. I don’t know how I overlooked the headless body business and the father’s insistence that the body is his daughter. Granted, that’s stretching credibility very thin.

interestingly, Wilson & Webb must’ve thought this first one was a weak effort because they recycled much of the plot (including duplicating the finale with the barn fire) when they wrote THE YELLOW TAXI. Ironically, I think that mystery (along with THE STARS SPELL DEATH) is one of the weakest in an otherwise original series that does a fine job of blending the detective novel with the horror novel.

I’ve reviewed four of the Stagge books on my blog. My favorites, so far, are DEATH MY DARLING DAUGHTERS with its diabolical murder methods and MURDER BY PRESCRIPTION for its very advanced discussions of euthanasia and ethical science experiments in the context of a rather gruesome murder mystery.

May 20th, 2017 at 6:44 pm

Thanks for the correct ID for Dr. Westlake in this book, John. I wonder if this was the furst (and only?) Stagge novel that Bill read and reviewed, and so didn’t think to identify the continuing character.

The only Stagge mystery that I remember reading is THE STARS SPELL DEATH, which you call weak. I must have thought so, since as I say, I don’t believe I read another.

And the next time I try one, if ever, I’ll keep in mind that gruesome and the macabre make up a deliberate part of the package. Forewarned is forearmed!

May 20th, 2017 at 8:37 pm

I agree with Bill: this is not a good mystery novel for the reasons he cites as well as others. My thumbs-down review in 1001 MIDNIGHTS points out additional flaws.

May 20th, 2017 at 10:56 pm

At the moment my copy of 1001M is some 3000 miles away, so I’ll have to wait a couple of weeks to read what you had to say, Bill. Sometimes when I get differing opinions on a book, though, what it does make me want all the more to read the it for myself. (I have a copy, but it’s also 3000 miles away, and on which shelf in the basement?)

May 27th, 2017 at 10:02 am

Attracted by the title, enjoyed the review — the second thumbs down I’ve read this morning.