Mon 28 Jan 2019

A Mystery Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: LADY IN THE DEATH HOUSE (1944).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[5] Comments

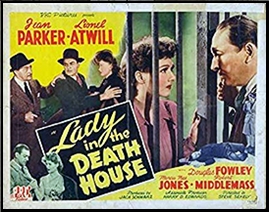

LADY IN THE DEATH HOUSE PRC, 1944. Jean Parker, Lionell Atwill and Douglas Fowley. Screenplay by Frederick C. Davis and Harry O. Hoyt, [based on the former’s story “Meet the Executioner” in the June 1942 issue of Detective Tales]. Directed by Steve Sekely.

Well, it’s different.

The story opens with Jean Parker walking that last mile to the Electric Chair. Then, as the door closes, we fade to Lionel Atwill as an avuncular criminologist, telling the tale of how he solved the baffling case of…. And we fade again into the first of many – many! — flashbacks.

It seems Parker was a secretary working under an assumed name for the self-righteous moral crusader (George Irving) who railroaded her dad into prison and suicide years before. She uses her position to get Irving’s old file on her dad…. But never mind that; the writers soon forget about it.

Parker is also being blackmailed by her sister’s shady boyfriend, who may have been responsible for the crimes pinned on her Dad. But don’t worry about that either, since the writers wander off on another tangent about halfway through.

What they concentrate on is Douglas Fowley (bad guy in more than 100,000 B-movies and the harassed director in Singin’ in the Rain) who is in love with Ms Parker. She loves him right back, but is put off by his employment: Whenever somebody on Death Row gets the Hot Seat, it’s his job to flip the switch. Things get even stickier when Jean is convicted of murdering her sister’s boyfriend (remember him?) and now it’s Doug’s job to pull the rug out from under the woman he loves.

BUT … it seems Doug also has a sideline as a research scientist, working on a way to restore life to the dead! And….

And nothing. Zip. Nada. Bupkis. Zilch. The writers once again wander off to different, if not necessarily greener, pastures, and Lady in the Death House eventually devolves into a desperate race against the clock to etc. etc.

I am reminded here of Harry Stephen Keeler’s trick of building a story by drawing scraps of plot and sub-plot from a hat. Anyway, Steve Sekely directs all this with as much style as he can muster, given PRC’s meager resources. He had his moments (Hollow Triumph) and gives this thing a sense of pace and even a flash or two of visual elegance.

What he can’t overcome is the crucial sequence where Parker is arguing with her sister’s beau, and their silhouettes are seen in incriminating outline from the street below. The more Sekely cuts from the street to the apartment, the more we see that the two of them ain’t nowhere close to that window – well, such are the vagaries of filmmaking at PRC.

I will add though that Fowley and Atwill seem delighted at playing good guys for a change and make the most of it. In fact, their thesping and Sekely’s desperate efforts at directing kept me watching, even as I wondered what the writers were smoking and where I could get some for myself.

January 28th, 2019 at 9:32 pm

Sounds as if they used the Bill Burroughs plotting method, write it all down on three by five cards and then throw them in the air and organize the book however they land on the floor.

I like Fowley, but you know you are in treacherous territory when he is the leading man.

Wouldn’t you love to see the blue pages on this script. It sounds as if it was rewritten from the top every day.

It also sounds like a lot of fun in the right mood.

January 28th, 2019 at 9:34 pm

Is Frederick C. Davis the pulp Frederick Davis?

January 28th, 2019 at 11:14 pm

Yes. He has a few writing credits in IMDb, but not many. The screenplay was Detective Tales. I’ll add this info to the credits at the top of the review.

January 28th, 2019 at 10:10 pm

Harry O. Hoyt, one of the writers on this, directed the 1925 silent version of The Lost World. Flicker Alley has two editions available, Blu ray, fully restored to its original length, and a DVD version, somewhat truncated.. Both have their strengths. The Blu looks fabulous, but the shorter version on DVD is, in my view, more fun.

January 29th, 2019 at 10:50 pm

Reminds me, in many ways, of True Crime, Clint Eastwood’s picture. Both on a similar subject with a charismatic central performance, and both have souls.