Sun 17 Nov 2019

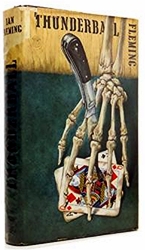

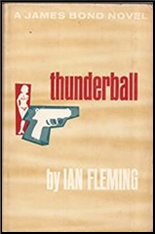

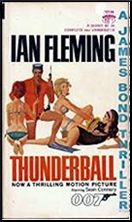

IAN FLEMING – Thunderball. James Bond #9. Jonathan Cape, UK, hardcover, 1961. Viking Press, UK, hardcover, 1961. Signet, US, paperback, 1962. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback. Filmed as: Thunderball (1965). Sean Connery, Claudine Auger, Adolfo Celi Directed by Terence Young; and as Never Say Never Again (1983). Sean Connery, Kim Bassinger, Klaus Maria Brandauer. Directed by Jack Smight.

The speech above is in response to Domino Vitale, the mistress, or as Ian Fleming has Bond tell us, the “courtesan de marque,†of Emilio Largo, at this point in the novel a “person of interest†in the investigation James Bond and CIA friend Felix Leiter are making as part of a global search for a missing nuclear weapons stolen from NATO, and being used by SPECTRE, a criminal terrorist organization lead by Ernst Stavro Blofied, to extort money from the West’s governments.

Domino’s brother was the pilot of the unfortunate missing NATO flight, enough for Bond and Leiter to be sent to the Bahamas on something of a wild goose chase well away from the hot spots where the real action is centered, and Largo, a wealthy and somewhat piratical figure has both the money and means of hiding the missing nukes.

Of course by this point we, the reader already know Largo is an agent of SPECTRE and Blofield, but as yet Bond doesn’t.

Thunderball was the eighth James Bond novel and followed a break after Goldfinger where the new James Bond had been a collection of short stories, For Your Eyes Only.

In fact Thunderball was the result of the author’s dwindling enthusiasm for his creation after a series of bitter disappointments about Bond’s screen fortunes. A proposed Hitchcock film of From Russia With Love had fallen through (Hitchcock ended up doing North by Northwest instead), and while sales for the Bond novels had rocketed with Doctor No and Goldfinger, the television series pilot “Commander Jamaica” that fell through had become the plot of Doctor No, and a short story collection consisted of five stories Fleming wrote as scenarios for a proposed television series, James Bond, Secret Agent, that had fallen through and ended up the hit series Danger Man with Patrick McGoohan, who despised Bond, as secret agent John Drake. Even a Ben Hecht scripted adaptation of Casino Royale had fallen through.

Thunderball itself might not even have seen print if a film director named Kevin McClory hadn’t approached Fleming about an idea for an original story and with screenwriter Jack Whittingham and Fleming written the screenplay that Fleming “novelized†as his James Bond novel for 1961. The legal mess the novels origin created would haunt the film franchise well into the 21rst Century before it was settled to everyone’s satisfaction.

If you are still with me, try to ignore all that history for a minute though, and go back to that paragraph I opened with, because to some extent that paragraph is what I’m really discussing here, not the history of the Bond franchise, but why Ian Fleming deserves to be read still and why there has been both a revival and a reassessment of his work in England.

Even if you hate Bond, despise the idea of a British hero (and I know American fans who never forgave Fleming and Bond for eclipsing the endless supply of American wanna-be Bond replacements who don’t cut it or don’t last), and loathe the film franchise, the fact is that Fleming, careless as he could be, sexist as he and his creation are, men of a different time and sensibility that both are, was actually a damn good writer whose instinct went well beyond what even he admitted.

In the chapter at hand, Bond is already in the Bahamas, and he and Leiter have been aboard Largo’s yacht, the Disco Volante, with a geiger counter seeking signs of the missing nuclear weapons. Bond has decided to get closer to Largo through Domino, and to hopefully, through seduction, to turn her against Largo as his “inside man.â€

Domino, is a typical Fleming heroine, attractive, but not flawless. She may have the “fine firm breasts†even Bondphile Kingsley Amis made fun of in his James Bond Dossier, but like most of Fleming’s women she a “bird with one wing down,†physically marred by one leg shorter than the other, and emotionally tormented by her past and her present.

In fact I’ve always thought that quite a few Bond women should have been played by either Gloria Grahame or Lizbeth Scott with their histories of wounds, and insecurities. Contrary to the image of the films they don’t just hop into bed with Bond, and in book after book he finds himself, reluctantly at first because he wants to get on with job and often is shown thinking so rather bluntly, playing psycho-therapist to a succession of abused and emotionally stunted women he rather surprisingly rescues not only from the dragon, but from their own self destructive course.

Bond in the books doesn’t win them over by his dark good looks or his sexual techniques and gifts. Hhe wins them over by being their way of reconnecting to life and normality. His most romantic gift turns out to be treating women well.

Along the way no few of them rescue Bond too, because, also despite the films, Bond usually begins or ends the book in need of physical and emotional rehabilitation. In fact that is where he starts Thunderball, drinking too much, drifting into too many messy affairs, losing his edge (It was one of those days when it seemed to James Bond that all life, as someone put it, was nothing but a heap of six to four against), and thanks to a fussy and newly enthused M (Was this the first sign of senile decay?) sent to a health spa, Shrublands, for a course of drying out (“I’d rather die of drink than thirst.â€), wheat-germ (…foods he had never heard of, such as Potassium Broth, Nut Mince, and the mysteriously named Unmalted Slippery Elm.), and massage.

Miss Moneypenny rather neatly skewers him when he threatens to spank her for her amused tone at his dilemma, “I don’t think you’ll be able to do much spanking after living on nuts and lemon juice for two weeks, James.â€

Being Bond, James Bond, 007, he stumbles onto an international plot by SPECTRE and is nearly killed, but not before a nasty turn with health food. He spots Count Lippe whose strange ring catches his eye before his first treatment. Yes, there is a sexy nurse and a mink glove, but this is wish fulfillment. I can’t imagine most readers would rather Nurse Ratchet give him a high colonic instead, at least not rather read about it.

It’s the fact that Fleming doesn’t need to spend a chapter telling us Domino’s life history that makes his choice to do so interesting. He could draw a tough but broken woman with a few lines if he wanted, as most thriller writers would have done, but instead he has Domino bothered by what people think of her as Largo’s expensive sex toy and in need of reassurance from Bond by telling him her backstory, and the key thing is that Bond’s response isn’t some sexist tough guy bull dragged out of the testicular fantasy of some chair bound pretend tough guy but sensitive and even thoughtful.

It really isn’t the response of a Lothario or Don Juan, it’s the thoughtful response of a man who for all his tough self talk likes women. Later there is a tender and sexy scene when he has to bite poisonous sea spines out of her wounded heel (symbolic of the one short leg that mars her beauty, something else Fleming didn’t have to include), and it leads to the first time they have sex and he turns her.

It pays off as well, because Domino not only helps, she is key to Bond’s success and saves his life in the finale.

And not once does Fleming or Bond speculate that women ought to be raped for wearing pants like a popular American spy novelist.

That it also goes to plot and provides Bond with information he needs about Largo and her brother is where the art lies, but Fleming could have taken more familiar thriller tracks to that same destination. That he doesn’t shows he still had that ambition to write thrillers that could be read not as literature, but with some of the pleasures of literature.

I recognize that last line is what many readers have against Ian Fleming and James Bond in the novels. How dare an entertainer slow down the bang bang and kiss kiss for write write and think think. It always amazes me when critics condemn Fleming, but praise the often prolix and dense le Carre as if being difficult and tiresome to read was a virtue in a thriller writer. I enjoy le Carre, but I’m damned if I can find much worth quoting in his work.

Fleming, however much you hate him, is quotable. His turn of phrase is more than sufficient, it is often eye catching and memorable. Like Raymond Chandler, or Georges Simenon, both of whom he admired, there is often something more to Fleming and Bond than just a wild yarn full of action with a bit of sex thrown in. There are passages of fine writing and even well drawn characters who come to life.

Or:

Or:

Or:

If nothing else, his villains, often drawn from life (Largo here is almost a caricature of Aristotle Onassis) raise the stakes considerably. If a thriller is only as good as its villain, then Fleming is very good indeed.

The truth is Thunderball is not Fleming at his best. Although the Fleming effect is in full swing and Largo, Domino, and Blofield lift the book well above the average level, it is a bit of disappointment after Doctor No and

If you still don’t like Bond, I have no argument or problem with that. This is about why I do still like Fleming and Bond, why I still reread them, and still find pleasure in them, and why no less literary lights than Kingsley Amis, William Boyd, and Sebastian Faulks were happy to write entries in the series.

Much as I enjoy many of the films, and fine as some of the film Bond’s have been, my first love will always be the books, and it is to the books I will always return.

November 17th, 2019 at 9:15 am

It is time for me to go back and read the books again. I read them all as soon as they came out in paperback, as did millions of other readers. But my memories of the books are now totally conflated and confused with my memories of the movies.

For example, if you’d asked me about THUNDERBALL before reading David’s review, I’d probably told you more about what’s in the movie rather than what’s in the book.

I also suspect that if I were to read the book now, it would be with Sean Connery in mind as Bond. All of the others that came along later were imposters, including Roger Moore. (But that never stopped me from enjoying his movies.)

My favorite Bond books are probably the same as almost everybody else’s: DR NO, GOLDFINGER and THUNDERBALL.

November 17th, 2019 at 9:35 am

Very thoughtful, very well written.

I put Ian Fleming in the same class as P G Wodehouse and Fredric Brown. They lavished their brilliance on genre books born to be dismissed by critics.

November 17th, 2019 at 11:49 am

Like Steve, I envision the movies when I think of the books, but I have enjoyed reading those books, as much or more than seeing the films. I wonder if my library system still has these? Hmm, I think I’ll check.

November 17th, 2019 at 5:41 pm

A most satisfactory and spirited defense of Fleming, though I was not aware that one was necessary. I love Fleming, faults and all. A major writer whose influence and work will last.

November 17th, 2019 at 6:24 pm

I noticed the occasional defensiveness in your review also, David. Have you been reading a lot of negative criticism of Fleming and/or Bond recently?

And as an example of amazing synchronicity, Emmy winning writer/director/producer/major league baseball announcer Ken Levine on his blog decided to talk about THUNDERBALL, the movie::

http://kenlevine.blogspot.com/2019/11/weekend-post_16.html

November 18th, 2019 at 1:48 am

Steve,

Fleming and Bond have been under attack since the earliest days (remember “Sex, sadism, and snobbery …”?). Since GOLDFINGER TIME MAGAZINE has been predicting the end of the film series, and it isn’t unusual to read American thriller writers whose chief complaint about Bond is that he is British and eclipsed his rather wan American competition (plenty of great American spy writers, but they tend to be more serious, and the more popular ones haven’t come anywhere near Fleming, not even Buckley and his Blackford Oakes who are almost the American equivalent of Fleming and Bond).

In England the publication of the Andrew Lycett bio of Fleming marked a major new look at his work, with most of his detractors dead and many of the newer literary lights less leftist than his older British critics who often attacked him from a political stand point as much as a literary one, and frankly the hindsight that no one had come along to fill the gap Fleming left, his work had a major revival.

As Kingsley Amis accurately pointed out once a few Christmases went by without a new Fleming Bond under the tree the tide against Fleming as a poseur and just a popular writer did turn.

Here, the movies remain popular, but the books haven’t gotten their due. They still get dismissed as nothing but silly escapism too often. I won’t go into the fear of too many American critics that they won’t be taken seriously if they admit to enjoying popular fiction, but anyone with any academic background knows that snobbery is real, or at least used to be. I still recall the horrified looks at Peter Straub on a literary forum once when he said he liked Elmore Leonard.

Many criticisms of Fleming are admittedly true. He is not a suspense novelist, and never pretended, or I would argue wanted, to be one (Adam Hall/Elleston Trevor is a far better action/suspense novelist, but Quiller remains faceless).

He writes to a formula (Umberto Eco did a fine book in which he shows how Fleming created and then subverted his own formula to stay fresh). He is a snob, in fact an upper middle class one, he is sexist, racist, and the Fleming effect is equal parts expert knowledge and humbug (Fleming was a master spy, but he barely knew one end of a gun from the other). His view of the Soviet Union is fairly accurate, but only because in his lifetime the Soviets of the 1950’s weren’t all that different than the ones he knew in the thirties when he was in Moscow and dealt with in the War. His attitude toward them shifts once Stalinism begins to fade, and they really aren’t the chief villains after FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE.

The same kinds of attacks can be made with equal authority against Raymond Chandler, who is the writer Fleming most resembles.

And of course the literary James Bond has gotten lost in the screen persona (even Fleming made Bond more Scottish after seeing Connery play him) and adventures so encountering the real Bond can be a bit of a shock if you haven’t read the books for a while.

Bond, for all of his complaints about women being involved in spying, is much less the kiss and kill, love them and leave them type than the screen Bond. In MOONRAKER he even gets his heart broken, doesn’t have sex with the girl, and gets told pretty plainly why. He considers marrying Tiffany Case and has a fairly long affair with Pussy Galore.

MOONRAKER also features the only bit of sadistic behavior on Bond’s part personally and it consists of catching one of Drax’s men searching his room and giving him a swift boot to the rear where he hits his head on the furniture. That’s it. Most of the other sadism is directed at Bond.

In GOLDFINGER, written at the time the defection of Cambridge spies Burgess and MacLean and the concerns over Alan Turing and his sexual preference were causing a witch hunt for homosexuals in British Security circles Fleming has Bond offer a defense complaining that it is totally unneeded and that homosexuals offer no greater threat to security than anyone else. Granted it isn’t a “woke” position now, but it was pretty “woke” for a Tory in 1959 writing a popular spy novel aimed at a heterosexual audience that probably agreed with what the government was doing. Even though one character in the book is a lesbian and another bi, the defense is in the book because Fleming saw an injustice, not because he needed it there.

Stephem Mertz,

If you read the criticism of the spy novel, particularly that from the seventies and eighties when several of the major books were written there is a strong backlash against Fleming, and an attempt to do to him what was successfully done to S.S. Van Dine and Philo Vance. It was doomed because of the films in Bond’s case, but it is clear in many of the books that there is a concerted effort to dismiss Bond and Fleming, to bury them and the attitudes they reflect. I still see the same thing being attempted a century later with John Buchan, who invented the damn genre (the modern spy novel with 1910’s POWER HOUSE, the spy novel itself around well before that).

It’s ironic too, because with exceptions like le Carre and Deighton, most of the writers who were supposed to replace Fleming and Bond as more serious and worthy are hard to come by while Fleming and imitators like Gardner, McCutchan, Mitchell/Munro, Hall (who managed to have it both ways with the excellent Quiller books), Leasor, George Mair, and Andrew York (Christopher Nicole) are all easily available in ebook form.

I grant the longevity of the movies accounts for much of this, but point out that the Bond books are still entertaining reads, and that the success of the recent more Fleming like new Bond novels by William Boyd and Anthony Horowitz (all set in the classic era of the Fleming novels) demonstrate there is still an audience for the Fleming Bond who has survived both the moves, the critics, the backlash, and the new century in remarkably good shape.

Whether he survives the last of my generation is still a question, but I trust in the quality of good writing to overcome a great deal.

November 18th, 2019 at 12:58 pm

I ask a simple question, and I get a long most interesting answer. Thanks, David!

November 18th, 2019 at 11:17 pm

I frequent numerous book sites and writing sites myself and yes I can confirm. Fleming is nigh-well being singled-out lately for a sirocco of withering scorn and criticism. He is lambasted.

Practically any reader’s review (of any of his titles) advances the precept of his ‘de facto’ blindspots. His critics take it as being without question that he is at fault, helplessly complicit in colonialism and sexism and racism.

You’ll have to take my word that I

have rallied against these notions. With spirit. Along the same lines as laid out above. Fleming was not just a prose stylist but a sharp, shrewd observer of post-war western society.

In ‘Diamonds are Forever’ (I’ve always maintained), his description of the surreality of 1950s America rivals Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’. Anyway I just deplore those who paint him with such a broad, black, brush as happens so often of late. It’s really the dizzy limit. Fleming and Joe Conrad, unfortunately bearing the brunt of today’s misguided political-correct hooey. Scholarship is just not there to support the general antipathy and venom.

Aside: yes, the backstory of EON’s ‘Thunderball’ (just what is a ‘thunderball’ anyway?) is an imbroglio long haggled over by the Bond fan-community. You can see it dissected still, on sites like commanderbond.net and so on.

I can’t readily encapsulize my feelings towards the novels as finely as the first post in this thread. I grew up with the full set of Bond books on my shelf and they had been passed-down and well-worn by elder siblings. Formative-year books for me.

As for ‘Thunderball’ the movie, I admire it very much; even after many repeated viewings. It is surprisingly, one of the most quintessential Bond romps –at least in my personal rankings. I rate it #3 in my esteem after FRWL (always #1) and Dr. No (always #2).

Always glad to see Fleming and his works discussed. He’s treated mighty unfairly these days. Member of the greatest generation.

December 14th, 2019 at 12:21 pm

Ben Hecht? Jeez, I didn’t know that. Are there any surviving copies of his screenplay?

I’m sort of a fan of the television version of Casino Royale — unAmericanize it and it would be among the best Bonds. It’s ironic that Orson Welles and Peter Lorre, both played the same Bond villain in the first two adaptations of the novel, and both versions were… mistakes. Although I’m fond of both.

January 17th, 2020 at 12:23 am

I’m not even sure how the Bond novels could have been successfully written in any other wise, except for how they were written. If Fleming had throttled back in any of his attitudes, those books might have turned out like any of a dozen other immemorable men’s adventure series. The lack of Fleming’s worldliness and old-school perspective is what distinguishes Bond books from the works of Alistair McLean. Bond novels are not –can not –ought not be ‘all action’. There must be dynamic peaks-and-valleys in narrative pace, “down-times” when Bond simply smokes. drinks, relaxes, and reflects. His emphatic Britishness is what makes those lulls engrossing. Bond’s rigidness, his conservative English ‘rigor’ towards the rest of the globe. Always present! That constantly pitched, tilted, skewed, slant against the slackness of ‘the other’ –makes even the slow sections of a Bond book, intriguing and challenging. I wouldn’t change a word of it. It’s the soul of the read! If today’s bland, globalized, identity-lacking audiences can’t handle it, well ….pfffff …

March 27th, 2022 at 12:06 am

Mike Gold,

I missed your question at the time, but if this does any good BATTLE ROYALE by Jeremy Dun is a history of the Hecht screenplay and contains much of it. It’s available on Kindle.