Tue 4 May 2021

Reviewed by David Vineyard: HARRINGTON HEXT (EDEN PHILLPOTTS) – Number 87.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[2] Comments

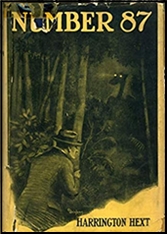

HARRINGTON HEXT (EDEN PHILLPOTTS) – Number 87. Thornton Butterworth, UK, hardcover, 1922. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1922. Wildside Press, US, hardcover/trade paperback, 2008, as by Eden Phillpotts. Prologue Books, US, trade paperback, December 2012.

The first sighting of the creature the world will come to know as the Bat in London is little but a curiosity, but soon it will become a world wide sensation of terror and horror, a monster striking from the sky and leaving death and destruction in its wake.

Eden Phillpotts, who under the pseudonym Harrington Hext penned fantastic thrillers, was a considerable literary light in his day well respected by critics for his regional novels; a recognized master of the mystery novel whose The Red Remaynes (1922) stands with Trent’s Last Case by E. C. Bentley as one of the first novels to create the Golden Age of the Classic Detective Novel; the man who convinced a discouraged Agatha Christie to keep writing because he saw something in her work; who partnered with notable writer Arnold Bennett (Doubloons); wrote early Science Fiction (Saurus and others); lost worlds (The Golden Feitch); and had more literary honors than we can list here, was born in 1862 (and died in 1961).

In the late Victorian Era he made his debut with a pamphlet for a railroad line that both pioneered and popularized an entire sub genre the railroad mystery with My Adventure on the Flying Scotsman, and one of his last novels (1951) featured a murder involving an experimental nuclear physicist . That would be a full career for any writer in any age.

But back to the central question, what is the Bat, and what is the secret of its reign of terror?

Alexander Skeat is the first victim, no mark on him but a tiny red spot. Yes, because this one is no fair play detective novel, a drug unknown to science is the culprit. Indeed in the tradition of the thriller mysterious drugs, monstrous bat winged flying creatures, and enough thrills, horrors, and mysterious doings for a dozen weird pulps fill the pages of this unrepentant extravaganza. Even Edgar Wallace could take a few notes from Phillpotts.

Our narrator is Ernest Granger, the Secretary of the Club of Friends and agent of the Apollo Life Insurance Company, both of who are intimately involved in the history of the Bat. His fellow club members General Fordyce and his scientist brother Sir Bruce, Rev, Walter Blore, Leon Jacobs Stockbroker, and Jack Smith, a barrister all figure in the action.

Drawn into the case by the death of Skeats, a scientific charlatan, the drama will take the men from London to New York, to Yugoslavia (Jugo-Slavia here), Russia, and China in a race to discover what the Bat is and who is behind it, and why it has targeted the relatively new Christian Science movement.

Like many books of the Post WWI era, Number 87 is concerned with the future, the fear of another Great War, and how to avoid that fearful fate.

That voice is key to the solution of the novel, a modern Prometheus (and no, the Mary Shelley reference is no accident) who reaches too far and through mere humanity becomes a monster rather than a hero of mankind is the culprit and the Miltonian figure at its center.

Like much popular fiction of the era the villain is no Fu Manchu or Bond villain, but a flawed superman of sorts, a figure both ultimately admired and feared, and in the end both he and his creation Number 87, the Bat, suffer exile rather than destruction more on the model of Nemo or Robur than the less noble villains to come.

Phillpotts is hardly hard-boiled or pared down as a prose stylist, but he can write and his works, while dated, are often still quite good reads. This brief scene when our narrator first spies the creature for himself is a good example.

Revelations, horrors, and terrors are to come before Granger and his friends find the remarkable solution to what the Bat is and who lies behind it much less why. It is admittedly old fashioned, but not bad for that. Certainly not to everyone’s taste, but well worth taking the time to find (easy in e-book edition if not hard copy).

Splendid blood and thunder that.

May 5th, 2021 at 6:02 am

Sounds like something I need to read — Thanks!

May 5th, 2021 at 8:00 pm

This is a fun book. Yes, it has the flaws of a lot of pre War thriller fiction, but Phillpotts was a damn good writer. Like Hugh Walpole, another bestselling critically acclaimed writer of the era who also wrote thrillers Phillpotts has a flair for this kind of thing, and is status as an early SF writer gives the fantastic element an extra boost.

I notice too with that cover the “Bat” looks suspiciously like Croww T. Robot from MST3K.

It also dawned on me why the hero’s name Ernest Granger was familiar. Ernest Granger is the character name of the oldest member of staff on the long running Britcom ARE YOU BEING SERVED. I guess after his run in with the BAT he sought out a less trying profession than insurance adjuster.