Wed 30 Jun 2021

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: THE VELVET TOUCH (1948).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[3] Comments

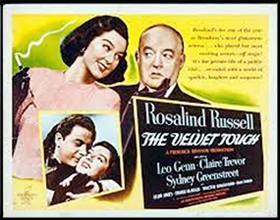

THE VELVET TOUCH. Independent/RKO, 1948. Rosalind Russell, Leo Genn, Claire Trevor, Sydney Greenstreet, Leon Ames, Frank McHugh, and Lex Barker. Written by Leo Rosten, Walter Reilly, William Mercer and Annabel Ross. Directed by John Gage.

Smartly written and well played, overwrought and predictable, this somehow feels like RKO’s attempt to do a Warners Joan Crawford flick of the time.

Rosalind Russell is a Broadway star with a string of comedy hits produced by Leon Ames — with whom, it’s hinted she has been quite close in the past. But as things open, their passion has cooled and she’s eager to move on to serious dramas with another impresario. She also wants to marry Leo Genn, and Ames finds this such an affront to his ego that he gets rough with her and is promptly clubbed to death with one of those hefty knick-knacks the gods of melodrama provide for such occasions.

Roz wanders in a Crawford-like daze from the scene, somehow not being spotted by the backstage crowd. Not so lucky Claire Trevor, who stumbles onto the body, gets her fingerprints on the murder weapon, screams for attention and faints.

A lengthy flashback fleshes out the relationships between the characters amid some scintillating theatre atmosphere, and then it’s back to the present day, and a murder investigation conducted by the redoubtable Sydney Greenstreet.

Up to this point it’s all been sort of soapy, but now things swing into an agreeable game of criminal cat-and-mouse, with Sydney making jokes about his weight and conducting a very laid back investigation that imperceptibly tightens around Ms Russell, who meanwhile makes herself busily neurotic in the best Joan Crawford tradition.

The Warners look is reinforced by the presence of Greenstreet and Trevor, and of Frank McHugh, doing his usual amiable sidekick stuff, but the real surprise here comes from Leon Ames, usually typecast as stolid types like the exasperated dad in Meet Me in St. Louis. Here, given a chance at flamboyance, he takes it and gallops across the screen like Barrymore in 20th Century. And like Barrymore, he dominates every scene he’s in.

The Velvet Touch may be a bit deliberate, lacking the dramatic fatalism of film noir, but to give it its due, it allows the supporting players some fine moments. Check out the scene where Sydney Greenstreet cautiously lowers himself into a folding chair and you’ll see what I mean.

June 30th, 2021 at 3:09 pm

I saw The Velvet Touch back in ’48 and any film with an angry female and no leading man leaves me cold. Russell, in my opinion, was not as much fun as Joan Crawford, and I mean Crawford in her Warner years, post Sudden Fear, a pass, although Roz as leading lady to Gable and Grant, quite appealing. Final thought: Leon Ames was always welcome.

June 30th, 2021 at 7:25 pm

Not really a Russell kind of film, I always preferred her in comedy though she certainly had the chops for drama. The main reason to watch this is Ames getting a bravura turn and Greenstreet’s sly policeman (not all that far from is role opposite Bogart as a murderer).

Not a great film, but worth passing the time with for pros at work all around. A bit stronger directorial personality for that cast might have worked wonders with it though.

July 21st, 2024 at 11:38 pm

I wouldn’t be surprised if this movie was one of the inspirations for Levinson & Link when they were creating ‘Columbo’.