Mon 3 Jan 2022

A Movie Review by Dan Stunpf: HUE AND CRY (1947).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[14] Comments

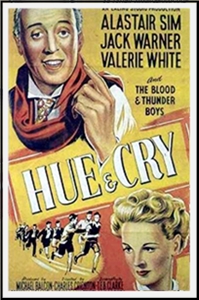

HUE AND CRY. Ealing Studios, UK, 1947. Fine Arts Films, US, 1951. Alistair Sim, Harry Fowler, Valerie White, Jack Warner, Paul Demel, and a mess of kids. Written by T.E.B. Clark. Directed by Charles Crichton.

Very uneven in tone, and all the better for it.

After defeating the Axis, post-war England faced a very different problem. Thousands of children, left with single parents, and largely unsupervised, roamed the bombed-out city, doing what kids do: playing in the ruins, getting in trouble of all sorts, looking for fun or maybe just the Better World their parents fought and sometimes died for.

This is the unlikely backdrop for T. E. B. Clark’s tale of mystery and adventure, and it’s a credit to all concerned that Hue and Cry neither shrinks from nor pontificates on the pervasive squalor. Rather, the filmmakers accept it as a fact of life — much as the children do — and go on about telling a ripping yarn.

The plot hangs on the notion that kids of all ages, as the saying goes, are hooked on reading the adventures of Detective Selwyn Pike in a post-war penny-dreadful titled Trump (The mind reels with clever comments, all regretfully omitted.) until a lad in his late teens (Harry Fowler, awkward, charmless, and perfect for the part.) finds a correlation between incidents in the weekly episodes and a real-life crime wave. Someone is sending coded messages inside the stories!

Duly inspired by Detective Pike’s example, Fowler and friends set out to catch the criminals, and it’s Buddies vs Baddies — with some surprisingly grim moments tossed in among the general merriment.

Top-billed Alistair Sim shows up for about five minutes of screen time as the timorous author of the stories, a part that suits him so well I really wish writer Clark had given him something funny to say.

But it’s the minors who carry this thing anyway, in scenes that lurch from kiddie stuff — like forcing a confession from a hard-boiled dame by scaring her with a mouse — to grim moments fleeing in a swampy sewer, then stalking and being stalked through a bombed-out tenement.

It all culminates in an all-out attack by the kids on the crooks — later borrowed for The Good Humor Man (1950) — as the children of the city descend upon the racketeers in a pitched and well-choreographed battle, intercut with moments of grim suspense as our boy-hero struggles with the master criminal in a tottering ruin that exemplifies the post-war disorder perfectly.

But there’s a moment that will stay with me even longer than all this. Just a scene of children playing, and one of them, perched atop pile of rubble, gleefully, endlessly, aping the sound of bombs dropping.

January 3rd, 2022 at 10:15 pm

Ealing’s answer to the Bowery Boys?

January 3rd, 2022 at 10:57 pm

Small as Sim’s role is, he is perfect for it. The film is a delight largely because it finds a balance between childhood “innocence” and grim reality.

January 4th, 2022 at 3:56 am

T.E.B. Clarke specialised in London films for Ealing Studios. Two others – Passport to Pimlico & The Lavender Hill Mob – are looks at other aspects of post-WWII London.

January 4th, 2022 at 7:56 am

“Jack Warner” is the notable *character actor* who’s name I recognize in that cast. Came across him in a “trick question” trivia game once.

January 4th, 2022 at 7:28 pm

Warner managed to become a star as everyone’s favorite policeman in numerous films and the father in a long running series of films about the comic adventuress of a post war British family and their adventures.

January 4th, 2022 at 9:29 pm

Thx thx thx. One more observation, provoked by a second look at the movie poster above. I’m reminded how popular ‘short pants’, (aka ‘knee pants’, or ‘knickerbockers’) were for boys’ fashion in that era. Especially any Brit movie from the ’30s and ’40s, practically any young scamp on screen is clad that way. Ever notice? It really marks the look and feel of films of that era. ‘The Fallen Idol’, or even the little boy in, ‘The Third Man’.

January 5th, 2022 at 5:37 am

They were just plain “shorts”, if I remember rightly, Lazy Georgenby. They were often compulsory wear. In the 1960s my grammar school made all boys under fourteen wear them, with long wool socks in the winter, which still left the knees exposed to the cold. Getting trousers was a sort of rite of passage.

January 5th, 2022 at 5:42 am

…and in England in the 1940s there was clothes rationing – a basic wardrobe could be bought at subsidised prices but anything more was very expensive. It’s quite likely that young boys were obliged to wear short trousers by the ration board as well.

January 5th, 2022 at 9:18 am

Cool info.

I remember too, a Charles M Schultz ‘Peanuts’ comic where Charlie Brown tries on his first pair. (All the boys in that comic are always in shorts except for maybe “Charlie Brown Christmas”.) Anyway he gloats, “Boy! Long pants sure make the man!”

This bears out what you’re saying.

Hope this is not too far off-topic but there’s also that great Johnny Mercer lyric.

“My momma done tole me, when I was in knee-pants, my momma done tole me, son …” you know that early ’40s hit.

January 5th, 2022 at 3:24 pm

I know it now! Thanks for the info – and the song.

It’s interesting: as Johnny Mercer’s mother was a woman, if he took her advice not to trust women he wouldn’t believe her and would disregard her advice which would really confuse him.

January 12th, 2022 at 12:10 am

Glad to tip you a wink, auld son. I love that song.

Just for added fun, do sometime take a gander at the story of how Howard Arlen and Johnny Mercer came to write that ditty, by looking up the anecdote on Wikipedia. I can’t speak for anyone else but it never fails to give me goosebumps.

January 12th, 2022 at 12:45 am

Blues in the Night sounds interesting too – a noir musical 88 minutes long with a plot as complicated as that!

January 12th, 2022 at 3:08 pm

Far and away the best thing about the film BLUES IN THE NIGHT are the montage sequences by Don Siegel, They are imaginative and full of good film technique. Siegel went on to become an important director.

January 12th, 2022 at 3:12 pm

No one in Lansing, Michigan during my boyhood went in for the “short pants” thing.

Us boys were expected to wear long trousers to church, as a sign of respect. To school too.

Both adult men and boys wore shorts to casual summer events: playing with other kids, backyard barbecues, etc. Never to “serious” events.