Sat 12 Mar 2022

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: RIO (1939).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews[12] Comments

RIO. Universal Pictures, 1939. Basil Rathbone, Sigrid Gurie, Victor McLaglen, Robert Cummings, Leo Carrillo, Billy Gilbert, Samuel S. .Hinds. Screenplay by Abden Kandel, Edwin Justus Mayer & Frank Partos. Directed by John Brahm. Current;y available om YouTube.

Contrary to director John Brahm’s film noir credentials (The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Brasher Doubloon) Rio is not an early example of that genre as often suggested half as much as a late blooming of German Expressionism and silent melodrama that anticipates those elements in film noir.

It probably didn’t help that the title Rio sounds more like a musical with Fred and Ginger dancing on the wings of an airplane than a melodrama loosely based on an international scandal.

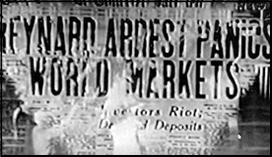

Here Rathbone is Paul Reynard (rather obviously named, reynard being “fox†in French), a fantastic Parisian financial figure whose massive empire proves to be merely a paper facade held together by unsecured bank loans upon bank loans and Reynard’s superhuman cool. When that empire collapses after a loan is called in by a rival taking many of his investors fortunes with it the whole thing implodes.

Loosely based on the Stavisky scandal that shook France and inspired a film (Stavisky, 1974) that starred Jean Paul Belmondo as Serge Stavisky the great swindler Rio adds to the character of the real life Stavisky a kind of cold genius and Svengali like influence over Reybard’s wife a once popular entertainer Irene (Norweigian actress Sigrid Gurie, Algiers, The Adventures of Marco Polo) who he possessively loves in his own controlling way.

Following the collapse of his financial empire the coolly unrepentant Reynard is arrested and put on trial. On conviction he is sentenced to a Devil’s Island like prison near Brazil and Irene, with his right hand man and bodyguard, Dirk (Victor McLaglen), agree to follow him to wait for him in Rio, Reynard urging her to divorce him and bragging to Dirk that he knows giving her that out will only serve to assure she doesn’t leave him out of loyalty. Even from his island prison he will continue to manipulate her, which is his only true pleasure.

There Irene takes up singing again in a bar owned by Roberto (Leo Carillo), a slinky type hoping to undermine her devotion to Reynard, while Dirk works as a bartender to be near Irene and protect Reynard’s interests.

Meanwhile in prison Reynard is the same arrogant Nietzschean ubermensch, content with his lot so long as he knows he still controls Irene even from afar, her letters proof of that control.

Back in Rio Irene meets drunken American Bill Gregory (Robert Cummings), an engineer who was responsible for a bridge that collapsed thanks to investors who supplied him with inferior materials. Now he is drinking himself to death in disgrace and shame.

But he has some charm, and unlike the cold Reynard he needs Irene. She helps him to reform, sober up, and get a job as an engineer, and this time he does a spectacular job of it. Redeemed and in love he convinces Irene to divorce Reynard and marry him.

Humiliated by the guards he has taunted because he letters have stopped and furious his control of Irene has been lost Reynard vows to kill the two lovers and plots escape, luring another prisoner into the suicidal attempt planning to kill the other prisoner and plant his id on the unidentifiable body,

Able to contact Dirk for help Reynard escapes, “dies,†murders his fellow prisoner, and is free, if only he wasn’t insistent on coming to Rio to murder Irene and Bill for their betrayal despite Dirk’s pleas.

Rio is a peculiar film. It seems closer to silent melodrama than modern film noir, and while it could be noir with just a turn here or there it isn’t in this incarnation, not quite.

Rathbone is perfect as Reynard, by turns cooly charming and sadistic, admiring his wife the way a snake looks at a bird, reading volumes into a glance. Gurie is quite lovely and persuasive both as the wife under Reynard’s hypnotic control and as the woman slowly freeing herself from his interest. While he had no need to model his performance on anyone Rathbone does, at times, seem to be channeling the kind of silent film roles often played by Conrad Veidt.

The film belongs to Rathbone though. Cummings has some good moments as a charming drunk but soon enough sobers up to be a somewhat standard, but far more skillful than usual, male ingenue. He seems a bit young for Gurie, but you can see the appeal after Rathbone’s snake like Reynard.

There are a number of evocative scenes and shots (nice cinematography by Hal Mohr) showing how well Brahm had absorbed the lessons of German expressionism and would later use them in his film noir works. Stylistically Rio is an attractive film.

It’s odd how misused and underused McLaglen is in this film. He has relatively little screen time and what time he does have is mostly in the kind of role you were more likely to see Walter Brennan or Thomas Mitchell in. McLaglen at this point was an Oscar winning actor and a star in his own right both teamed in films with the likes of Edmond Lowe and Chester Morris, and as a lead on his own having played the lead in two John Ford films (The Informer, Black Watch).

It’s downright strange to see him play so small, if important, a supporting role in the film. Leo Carrillo is wasted too as the wastrel owner of the place where Irene performs. He is suggested as an oily type after Irene’s honor, but is awfully jovial about giving up when she ends up with Cummings. His role mostly consists of trying to scare gossipy waiter Billy Gilbert into shutting up. He never more than annoys Irene a little.

Rio is an odd film. Rathbone is the main reason to watch, but by no means the only one. It’s also interesting to note American audiences in 1939 would be expected to immediately draw the inference to the Stavisky scandal that rocked France earlier in the decade. I’m not sure a modern film would dare to imagine an American audience would be that familiar with an international scandal, but here the film expects the audience to have some familiarity with those events and connect Reynard with Stavisky effortlessly.

March 12th, 2022 at 6:59 pm

In a contemporary take, the figure would be Madoff-like. I am halfway through Trollope’s The Way We Live Now, and that is even nearer despite having been published in the 1870s.

March 12th, 2022 at 9:19 pm

Barry,

No question the character is in a fairly long line of financial Svengali types in fiction from Shakespeare’s unfortunate Shylock on.

It isn’t surprising to find one in Trollope’s legalistic novels.

Paul Feval’s famous novel and play LE BOSSU (often filmed, most famously as Philippe de Broca’s EN GARDE) features an aristocratic financier brought down by our hero, Lagardere) who poses as his hunchback financial genius avenging the death of his mentor and friend. Easily among the most popular villains post WW I were financiers starting wars for profit and it got no better after the Crash.

The Stavisky scandal in France had political tentacles in the growing fascist movement in France as well was one of the great scandals of the era, perhaps the century, equal at the time to Madoff. It toppled not only financial institutions but governments.

Sadly, it is hard to find the English subtitled or dubbed version of the 1974 Alain Resnais film mentioned above. A shame because it features a fine performance by Belmondo as the extravagant title character and a late role by Charles Boyer in a rare dramatic part at that time in his career.

March 12th, 2022 at 11:28 pm

David,

While all you have written is so, they skirt the single issue tying all these men and events together with a bright red ribbon. From Shylock to Stavisky, Melmotte, a fictional character created by Anthony Trollope, and the entire tragic Madoff family.

March 12th, 2022 at 11:29 pm

Oh, add Jerome Weidman’s novel to the above.

March 13th, 2022 at 1:46 am

In spite of fine cast and what sounds like a good story, this is not a particularly well-known movie. Not only is it one that I’ve never heard of before, there is only one other external review for it on IMDb, other than David’s, and that is the contemporaneous one for it from the New York Times.

The opening lines:

“John Brahm’s impact on the Class B picture is producing one of the strangest sound effects in recent cinema history. It is that of an unmistakable B buzzing like an A. If his “Rio” (at the Globe), like his “Let Us Live” of last season, is not a complete triumph of directorial mind over routine plot matter, it represents its victory in a few skirmishes at least. Better still, it represents an effort of a new director to break away from the established pattern and try something new.”

March 13th, 2022 at 3:25 am

I found RIO absorbing. Bob Cummings was one of the few leading men in Hollywood who could romance a married woman without losing audience sympathy.

March 13th, 2022 at 7:08 am

Shylock is a much less powerful character than any of the others, Barry Lane. There’s an interesting play – The Lady of Belmont by St. John Ervine – set some years after The Merchant. Shylock, with no religious prejudice against him, is richer than ever and a friend and adviser to the Doge and all the marriages that ended The Merchant have been disasters.

Is Melmotte Jewish? He’s given all the tropes of the super-swindler, but I don’t think he’s said to be Jewish. There are elements of George Hudson, the Railway King, to his character.

March 13th, 2022 at 3:31 pm

[…] The Mystery*File blog posts reviews of films both familiar and of more obscure. Three recent posts have seen coverage of The Steel Key (1953) by David Friend, and Dave Vineyard has reviewed Broken Lance (1954) and Rio (1939). […]

March 15th, 2022 at 11:34 pm

Whitaker Wright is another famous British fraudster. This scoundrel’s rise and fall was a source of fascination for HG Wells.

March 17th, 2022 at 12:39 am

St. John Ervine’s play seems the moral equivalent to Jules Lermine’s Monte Cristo sequels. Of no consequence. Unrelated other than to exploitation.

March 17th, 2022 at 2:01 pm

I’ve never read – or heard of – Lerminaso I can’t say if your dismissal of him is justified but to assume that all sequels are “of no consequence. Unrelated other than to exploitation” is making a pretty broad assumption. Leaving aside the question of quality or other topics (as in Mistress Masham’s Repose, for example), the difference between sequels to novels or films and plays is that every production of a play is a “remake” and knowledge of possible futures for the characters affects every production and the way it is put on.

March 17th, 2022 at 2:51 pm

Not that every sequel is of no consequence, but every ‘rape’ of an original is just that.