Mon 4 Jul 2022

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: CONE OF SILENCE (1960).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[6] Comments

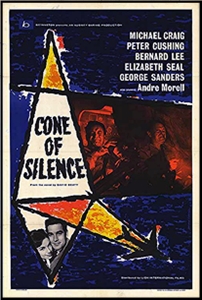

CONE OF SILENCE. Baring, UK,1960; released in the U.S. as Trouble in the Sky. Michael Craig, Peter Cushing, Bernard Lee, Elizabeth Seal, George Sanders, Andre Morell, Charles Tingwel, Gordon Jackson,Noel Willman, Marne Maitland, Jack Hedley. Screenplay by Robert Westerby and Jeffrey Dell, based on the novel Cone of Silence by David Beaty. Directed by Charles Frend.

“Why did the Phoenix fail to take off?â€

Civil Aviation drama had been around since the Thirties (Five Came Back isn’t even the first), almost from the birth of civil aviation, both in popular fiction and in films, but after the Second World War what had been a growing genre pioneered by the likes of Nevil Shute took off with writers like Ernest K. Gann, Arthur Hailey, Hank Searls, Ian Gordon, Hammond Innes, Gavin Lyall and many others discovering the drama and thrills in the sky.

The books they produced seemed a natural for the screen, and when Gann’s mega selling The High and the Mighty became a block buster movie directed by William Wellman with John Wayne, an all star cast, and a handful of Oscar nods, not the least for the haunting Dimitri Tiomkin score, the gates were down and Hollywood skies were crowded with commercial aircraft flying alongside all those fighter planes and bombers that had been in the glamorous Hollywood skies since Wings.

Zero Hour, Julie, Storm Over the Atlantic, No Highway in the Sky, Fate is the Hunter, The Crowded Sky and others success at the box-office meant the flaps were up and engines revved. After all there was everything you needed right there, a disparate group of people trapped in a box in the sky their fate dependent on a handful of professionals, dramatic vistas of sky, taut faced men on the ground trying to guide the wandering souls home, sleek modern aircraft half technological marvels and half terrifying innovation that seemed to go against common sense, and better than that you could do this on television with stock footage and cheap sets and still do it pretty well.

Planes were dropping out of the celluloid sky so fast some of the major airlines worried about their image and wouldn’t cooperate unless the film emphasized how safe flying was. Drama is one thing, but money is money.

It was all there, soap opera, heroics, comedy, primal fears, and the soaring ambition of conquest and pioneering. Add to that that other popular Post War source of drama board room intrigue to spice things up.

British writer David Beaty was a flyer, as were many of those who wrote about aviation, a man who got both the romance of the great silver birds and the romance of the slide rules that built them and got them in the air. His novels, including this one, Cone of Silence, were international bestsellers that put human beings in the cockpit and on the ground, gave the technicians faces and the corporations names and dared to remind people that despite how it was sold this was still a vast experiment in the sky, an adventure for all the commercial professionalism surrounding it.

Ernest K. Gann called his most personal book on flying Fate is the Hunter, because like a lot of old pilots who got started before the War he had a near superstitious belief that the more you flew, the longer you dared fate, the more likely you would push your luck too far. That was not a popular idea with the aviation industry trying to sell seats to people used to a nice boring old train.

That idea that a pilot’s number might be up versus something might be wrong on the ground is the chief cause of tension in Beaty’s book and the film based on it.

Sometimes both could be true.

Based on a 1958 incident involving the de Haviland Comet, Beatty spins a cautionary tale about veteran Captain George Gort (Bernard Lee) a good pilot who survives a terrible crash and finds himself grounded because of it after his tough cross examination by Sir Arnold Hobbes (George Sanders). His fate is left in the hands of Captain Hugh Dallas (Michael Craig) who tests veteran pilots on the new Phoenix jet under the direction of Captain Mannheim (Andre Morell), and who tests Gort when he is given a second chance and decides he is fit to fly.

Gort is a perfect pilot, by the book. Not a seat of the pants type like so many younger pilots.

Gort is back on the Phoenix and Pickering (Noel Willman) who designed the plane is none to happy, neither is Captain Judd (Peter Cushing) who wants younger men on the plane. Meanwhile Dallas is interested in Gort’s daughter (Elizabeth Sellars) who still resents him.

After flying with Gort in India Judd wants him suspended when there is an incident of Gort coming in too low in Judd’s opinion. Another pilot proves to Dallas that Gort wasn’t at fault for the things Judd has accused him of, but Judd is going behind Gort’s back to try to get him grounded.

Even after Gort saves a plane from crashing in a storm when a window on the Phoenix fails Judd and Pickering are still against him as if his very existence threatens them, and in a way it does.

When Gort crashes again at exactly the same weight of cargo and on the same kind of runway in the same hot humid conditions and this time dies Dallas is certain that Judd and Pickering are hiding something and sets out to find out what, and isn’t going to let Sir Arnold buffalo this verdict into pilot era certainly when he discovers a history of trouble on takeoffs for the Phoenix that pilots, including Judd, haven’t been reporting to avoid getting into trouble and Dallas confronts both Judd and Pickering because sooner or later another pilot will be taking off in exactly the same conditions as Gort did and inevitably crash.

It’s well done drama with more than enough suspense and an outstanding cast including Noel Willman as Pickering the touchy designer of the plane and Andre Morel the chief pilot who decides to keep Gort on, Peter Cushing suspiciously against Gort, with George Sanders having a nice turn as a snide attorney (what else would George Sanders play, Santa Claus?) whose courtroom dramatics were largely responsible for Gort’s conviction in the first place.

“I’m sure you’re just as anxious to find out what happened as the manufacturers?†George Sanders as Sir Arnold Hobbes to Bernard Lee’s Captain Gort.

Was Gort just doing his job, was everyone just doing their job, or is there something wrong, something the manufacturer and the airline don’t want the public to know because they might be libel for the people who died? Business as usual, cover up, or just the curtain that descends when tragedy and money are both in the pot, that is what the hero and the viewer are asked to judge. There is no melodrama here, just professionals trying to balance business, safety, professionalism, and progress with the stakes much higher than than can be measured in an accounting book.

Granted the ending when it comes moves a bit to fast, a bit too pat, and without some of the books cynicism, but along the way it is well acted and written moves along quickly, and more than the usual mix of soap opera and melodrama in aviation films asks some tough questions about where business, progress, and mere men fit in an inherently dangerous business.

The ending may be happy and just, but it doesn’t pretend it has really dealt with problems that will always raise their head.

There are many cones of silence that contribute to the tragedy here Beaty and the film are suggesting. That of tough professional pilots who keep problems to themselves rather than risk their careers, that of scientists more interested in their project and their years of work, the bigger picture, than small vital problems, and that of individual men who put ambition, success, and glory above individual lives in labs, in board rooms, and in courtrooms.

July 4th, 2022 at 9:35 pm

What a cast! Of course, hearing the phrase “cone of silence,” boomers will remember the CONTROL security device in “Get Smart” that was anything but.

July 4th, 2022 at 10:01 pm

My first thought was that the GET SMART connection was why they changed the title of the movie for its US release, but no, the TV show came along some five years later.

David, of CONE OF SILENCE or TROUBLE IN THE SKY, which is the better title?

July 5th, 2022 at 7:59 pm

The “Cone of Silence” of the title is a key part of the plot, a narrow beam which pilots have to zone in on to make instrument landings while blindfolded. It’s a metaphor for why the disgraced pilot was the first to crash, because unlike the others he always did everything perfectly by the book, while other pilots had lied about following the book in the conditions where they avoided crashes. He was ironically doomed by doing everything right.

In that sense Cone of Silence is by far the better title, but the audience can’t know that coming in so for American audiences who tend to be more on the nose TROUBLE IN THE SKY, the rather unimaginative and colorless title might work better.

When Nevil Shute’s similar NO HIGHWAY was filmed both American and British releases seemed to feel they had to be more on the nose, NO HIGHWAY IN THE SKY.

Most of the time the producer or studio just wants to contribute their two cents for no real reason. Posters, trailers, and radio spots for the film could have made either title work. Somebody just wanted to stick their finger in the pie and claim it as their own. A decent campaign could have sold either title.

There is no real reason that John Castle and Arthur Hailey’s RUNWAY ZERO-8 aka FLIGHT TO DANGER was better as ZERO HOUR. ZERO HOUR made no more sense and said no more about the plot than either title, someone just liked it better.

July 5th, 2022 at 9:50 pm

My take: CONE OF SILENCE is too specific, and

TROUBLE IN THE SKY is too generic, keeping in mind

that I’ve never seen the movie.

September 12th, 2022 at 12:33 am

I’ve probably suffered through as many tedious air dramas as the next feller.

But in the category of “cheesy”: I’ll abjectly go on record stating my enjoyment of the original Alex Hailey ‘Airport’ starring Burt Lancaster (and a lot of our other favorite actors). I just think it’s a good bellyful of simple-minded fun. Who can forget Van Heflin as Guerrero, the ultimate madman you never want to sit beside?

With slightly more of a hang-dog expression on my mug, my #2 is “Airport ’75”. The action sequences are out/out crazy. Plonking he-man Heston via a steel cable, into the cabin of a in-flight 747, from the hatch of a Sky-King helicopter or whatever it was? Simply outlandish.

Non-cheesy: I admire “Five Came Back”; “No Highway”; “Sole Survivor” and “Flight of the Phoenix”.

October 24th, 2022 at 12:46 pm

Pity that people have commented who have not seen this movie, or talk of things with no relevance to it. Not helpful to others who just want some honest feedback on this production.