Thu 28 Jul 2022

EAST MEETS WEST: AKIRA KUROSAWA ADAPTS ED MCBAIN, by Matthew R. Bradley

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[8] Comments

AKIRA KUROSAWA ADAPTS ED MCBAIN

by Matthew R. Bradley

Akira Kurosawa’s Tengoku to jigoku (Heaven and Hell, aka High and Low; 1963), based on Ed McBain’s tenth 87th Precinct mystery, King’s Ransom (1959), epitomizes a pair of fascinating, complementary trends. One was the penchant of Kurosawa, arguably Japan’s greatest filmmaker, to adapt writers as diverse as William Shakespeare (Throne of Blood, 1957; Ran, 1985), Fyodor Dostoyevsky (The Idiot, 1951), and Maxim Gorky (The Lower Depths, 1957). The other is the use of McBain’s all-American romans policiers for films from France (La soupe aux poulets, 1963; Sans Mobile Apparent, 1971; Claude Chabrol’s Blood Relatives, 1978), Czechoslovakia (87. RevÃr, 1970; Panenka, 1980) and elsewhere.

As McBain, Salvatore Albert Lombino (aka Evan Hunter) was the acknowledged master of the police procedural, the series comprising 55 books over half a century, and possibly inspiring Hill Street Blues. Its innovations included a “conglomerate hero in a mythical city…[that] was like New York but not quite New York,†with analogs for each borough; he had planned that “one cop can step into the spotlight in one novel, another in the next novel, cops can get killed and disappear from the series, other cops can come in, all of them visible to varying extents in each of the books…†The novel was faithfully adapted by McBain himself as “King’s Ransom†(2/19/62), an episode of the 87th Precinct show.

It opens in the home of factory owner Douglas King as he confronts an attempted coup by investor Frank Blake, sales head George Benjamin, and fashion co-ordinator Rudy Stone, members of the board of directors of Granger Shoe Company who seek his voting stock to override the “Old Man†and abandon quality shoes for the more profitable low-priced field. Unknown to them, King plans to send assistant Pete Cameron up to Boston with a check for $750,000 so that his lawyer, Oscar Hanley, can sew up sufficient stock to effect a counter-coup. King gets a call demanding $500,000 for son Bobby, snatched while playing in the back woods with Jeff, son of widowed chauffeur Charles Reynolds.

Then, Bobby bursts in, and it quickly becomes clear that Sy Barnard and Eddie Folsom — whose wife, Kathy, was waiting at a rented farmhouse, thinking they were pulling a final bank job before the couple can head down to Mexico for a fresh start — have grabbed the wrong victim. Eddie has cobbled together a Rube Goldberg contraption out of equipment from a series of radio-supply thefts and monitors the police frequencies, learning of their error. Phone company man Cassidy sets up a wiretap, yet the next call, to say they want the ransom paid regardless, is too brief to be traced; needing the money for Hanley, King refuses to pay despite Diane’s threat to leave, his son’s pleas, and any adverse publicity.

Adrian Score, who tells King he knows who the kidnappers are and can get the boy back for a fee, is recognized by Det. Meyer Meyer as a con man and ejected; in the squadroom, Det. Hal Willis and Artie Brown, Sgt. Dave Murchison, and even commander Capt. John Frick have their hands full with well-meaning calls. Kathy warns Eddie that Sy plans to kill Jeff either way, but is caught trying to sneak him out, and after Folsom drives off to phone King with his instructions, the boy leaps to her defense when Sy threatens her with a switchblade, interrupted by Eddie’s return. Doug learns that Pete (whose duplicity was presaged by an extramarital affair with Diane’s friend Liz Bellew) has sided with the rest.

Det. Steve Carella advises King to tell the kidnappers he has the money, just to buy time, so he departs in his Cadillac with a carton full of newspapers — and Carella on the floor in back. At the King estate, Det. Peter Kronig and Cotton Hawes find a tire track and paint scraping that enable the police lab’s Sam Grossman to identify their car as a stolen gray 1949 Ford, but Sy uses the radio to avoid road blocks. Eddie transmits to the car phone, giving King directions piecemeal to avoid pre-emptive police action, and plans to have him drive past a remote spot where Sy waits to pick up the carton, dropped out of view of any possible pursuit, and make off with it before anybody realizes King no longer has it.

At a toll booth, Steve hands Patrolman Umberson a note pinned to his badge, alerting him to the situation, and he calls the precinct, but Kathy is determined to extricate herself and Eddie from what she fears may turn into a capital crime, so she shouts both their location and Sy’s into the open mike. As Carella and King surprise Sy in the woods, with Doug battering him into submission despite knife wounds, police raid the farmhouse to find Jeff safe and sound. Repaying Kathy’s kindness, he stubbornly insists he’s been alone since Sy — who corroborates his story to avoid the mark of the squealer, shielding the Folsoms’ presumed Mexican getaway — left; Doug mounts his takeover, and reconciles with Diane.

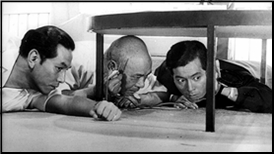

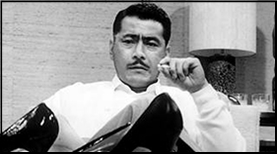

High and Low features Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura, seen separately or together in almost every film from the first phase of Kurosawa’s directorial career, up through Red Beard (1965). The co-scenarists were Hideo Oguni, his collaborator on a dozen projects from Ikiru (1952) to Ran; Eijirô Hisaita, who’d worked with him as early as No Regrets for Our Youth (1946); and Ryûzô Kikushima, who produced the film for Toho Co., Ltd., with Tomoyuki Tanaka, the driving force behind the Godzilla and other kaijū eiga (giant monster) films for which the studio is best known. Composer Masaru Satô was another kaijū mainstay, as were Shimura and supporting players Jun Tazaki and Yoshio Tsuchiya.

Baba (Yûnosuke Itô), sales and operations; Kamiya (Tazaki), marketing; and Ishimaru (Nobuo Nakamura), design, ask Kingo Gondo (Mifune) to join his 13% of the stock with their combined 21% to vote out the Old Man, holding 25%, and replace him as president of National Shoes with Baba. Kurosawa adds a marvelous visualization as Gondo tears their flimsy prototype to pieces with his bare hands, then is threatened that they can vote with the Old Man and throw him out. As right-hand man Kawanishi (Tatsuya Mihashi) shows them out, they offer to make him a director if he helps them, and here we first see Jun (Toshio Egi) and chauffeur Aoki’s (Yutaka Sada) son, Shinichi (Masahiko Shimazu).

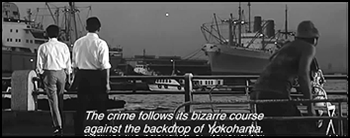

Playing sheriff vs. outlaw, they switch outfits, accounting for the confusion after Kingo tells wife Reiko (Kyôko Kagawa) that Kawanishi will be off to Osaka with a deposit of Â¥50 million to bring his holdings to 47%. Chief Inspector Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai) and his men arrive in a delivery van, aware that with a telescope, the house is visible from the streets below, literalizing the film’s U.S. title. Resetting it from a frigid “Isola†October (weather features prominently in many of the books) to a sweltering Yokohama summer, Kurosawa sharply contrasts Gondo’s air-conditioned hilltop home with the slums, where much of the action occurs, an “inferno†that, per the kidnapper, “feels like 105 degrees.â€

Refusing to pay the Â¥30 million, Gondo says the kidnapper seems obsessed: “He wants to humiliate me, see me suffer.†Using the Tohoscope wide-screen image to great effect, Kurosawa tracks in and out of a single three-minute cut to capture, in the same frame, all the drama of Reiko consoling Aoki as he debases himself to beg for help, Jun plaintively asking when Shinichi will return, and the conflicted Gondo telling Kawanishi to postpone Osaka, with the police listening awkwardly in the foreground. The chief sets up a special investigation, placing the whole prefectural police force at Tokura’s disposal with a clear mandate (“Save the child first, then catch the kidnapperâ€) paralleling the film’s structure.

After a night of soul-searching, Gondo remains obdurate, unwilling to sacrifice his future and all he’s worked for, and tells Kawanishi to proceed, but when he balks, citing Reiko’s wishes and public opinion, Kingo intuits that he has been sold out. Equally at home as a samurai or an aspiring footwear tycoon, Mifune brings his trademark intensity to the role, grappling with his betrayal and no-win situation. Knowing he is being watched, he says he’ll pay, demanding to see Shinichi, and then — in the first significant departure from the novel — calls the bank for the cash, to be taken aboard the Kodama No. 2 express train in two briefcases, a deliberately conspicuous style that the kidnapper will have to get rid of.

They contain powders emitting a putrid smell if gotten wet or pink smoke if burned; after the police record as many non-consecutive serial numbers as possible, Gondo is told, via rail phone, to toss the cases out the narrow washroom window between Kozu and Atami, where the boy will be at the foot of the Sakawa River bridge. Tokura has Chief Detective Taguchi (Kenjirô Ishiyama) — nicknamed “Bos’n†due to his work at the harbor — and the others snap still photos and 8mm footage from the train, and Shinichi is duly released by a female accomplice. True to the spirit, if not the letter, of McBain, with more than half the 143-minute running time to go, Kurosawa meticulously details the ensuing manhunt.

Gondo elicits national acclaim but unsympathetic creditors threaten to seize his collateral. Meanwhile, a farmer who saw the cash picked up leads to skid marks and paint scrapings from a stolen gray ’59 Toyopet Crown, and Shinichi recalls being at a house with a view of the sea and Mt. Fuji, yet he was doped with ether, and the kidnapper wore a mask and dark glasses. The abandoned car is found with large amounts of fish blood and oil, and the distinctive sound of the Enoshima trolley is detected in one of the taped phone calls, narrowing their search; at the nearby Koshigoe fish market, the Bos’n learns of a cape in front of Enoshima whose view matches the one drawn by Shinichi, who leads Aoki there.

As Taguchi and a colleague, arriving just behind them, chide Aoki for playing detective, Shinichi spots the house, where caretakers “Uncle and Auntie†(the de facto Folsoms) are found dead of heroin overdoses. At a news conference held by his boss (Shimura), taking a leaf from McBain’s The Pusher (1956), Tokura posits that the kidnapper silenced them with unexpectedly pure heroin, apparently after a blackmail attempt, and requests a press blackout to let him believe the addicts may still be alive. Instead, they report on Gondo’s ouster from National Shoes, provoking a boycott, and run a planted story about a ¥1,000 note from the ransom having been spent, complete with a photo of an identical briefcase.

¥2.5 million is recovered from the accomplices and returned to Gondo, who refuses to be an “ornament†when Kawanishi claims he’s fought to change the board’s mind; Shinichi draws a picture of the kidnapper that, despite the facial coverings, reveals a handkerchief worn around his wrist. In a striking visual touch, Jun draws their attention to pink smoke in the monochrome image, rising from an incinerator used by hospital personnel, where a possible medical intern brought a cardboard box. Ginjirô Takeuchi (Tsutomu Yamazaki), spotted with a wrist wound, has an apartment in Nishi Ward facing Gondo’s house, next to a suspect pay phone, and had treated the addicts for pulmonary edema and withdrawal.

Tokura sends him a facsimile (made from a tracing on the pad) of their note demanding more heroin, so Takeuchi, forced to make a buy, is followed to “Dope Alley,†where — menacing in his reflective shades — he picks up a junkie and takes her to a flophouse as a fatal guinea pig. Nailed at the hideout, he’d spent only ¥20,000 on heroin, so Gondo gets back the rest of the ransom…too late to save his house. Condemned, Takeuchi insists on speaking with Gondo, now making shoes again for a small company, and says, “From my tiny room, your house looked like heaven,†hatred and resentment giving him a reason for living; he summoned Kingo in a last show of defiance, but his arrogance turns to hysteria.

No mere acorn, King’s Ransom gave Kurosawa the solid foundation for a more nuanced moral exploration and one that, for Gondo at least, has the opposite outcome. Reducing the accomplices to ciphers — glimpsed only in long shot, filmed from the train, or via the legs of their corpses — enables him to focus completely on Gondo’s relationship with the kidnapper, whose impersonal motive in the book was purely profit-driven, and on a more elaborate investigation that is nonetheless wholly in the McBain style. The Japanese title is also made explicit, particularly in the almost Dantean horrors of “Dope Alley,†whose hopeless denizens, grasping at any passerby, anticipate Night of the Living Dead (1968).

July 28th, 2022 at 9:02 pm

Well done review of the film and the book and how and where they differ. I suppose purists might complain about the differences between the two, but for me it was two fine takes of the same story, recognizable, but fulfilling different needs as books and films do.

Mifune is one of those rare stars who is both always recognizably some version of himself and also a kind of everyman, short hand for what directors like Kurasawa and others want to say in any given film.

July 29th, 2022 at 1:26 am

That last image used is from a different production: High&Low: The Story of S.W.O.R.D. is an action series about gang wars with really stylish fights, but has nothing to do with High and Low/King’s Ransom.

July 29th, 2022 at 7:45 am

That photo came from the Criterion page for the movie but I’ve replaced it with different one, one that I’m sure is a good one, I hope. Thanks!

July 29th, 2022 at 8:06 am

David, my sentiments exactly–a book (or short story or whatever) and film can be different yet equally viable…and occasionally, the film is even an improvement! If you’re interested, I’m working on an exhaustive overview of the 87th Precinct TV series, with a special focus on the large number of books it adapted, some by McBain himself (who also contributed an original teleplay, “Line of Duty”). That should be appearing in bare*bones in about six months.

July 31st, 2022 at 3:29 pm

In 1985, this basic plot — kidnappers grabbing the wrong child — was borrowed for the first episode of The Equalizer.

July 31st, 2022 at 5:50 pm

The film High and Low has terrific story telling. It is really gripping.

August 20th, 2022 at 4:57 am

Just back from watching High And Low on TCM – followed by “King’s Ransom” from the 87th Precinct DVD set.

If you’ve got the materials, I recommend that any or all of you do the same, for your own edification.

I dare say that you’ll get a kick out of some of the casting …

Beyond that, I’ll stand down in favor of Matthew Bradley’s fortcoming bare*bones write-up, which ought to do the contrasts between a 2:20 Japanese feature and a :50 minute US-TV show in proper style.

Back to sitting and waiting …

January 12th, 2023 at 3:02 pm

Change of plan, Mike: my page-to-screen analysis of the 87th Precinct TV series will actually be appearing right here; watch this space…