Sun 20 Nov 2022

A Locked Room Mystery Review by David Vineyard: JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Crooked Hinge.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[4] Comments

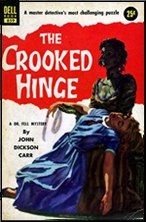

JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Crooked Hinge. Dr. Gideon Fell #8. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1938. Popular Library #19, paperback, 1944. Reprinted many times.

No ivy had been allowed to grow against its face. But there was a line of beech-trees set close against the house at the rear. Here a newer wing had been built out from the center—like the body of an inverted letter T—and it divided the Dutch garden into two gardens. On one side of the house the garden was overlooked by the back windows of the library; on the other by the windows of the room in which Sir John Farnleigh and Molly Farnleigh were waiting now.

A clock ticked in this room. It was what might have been called in the eighteenth century a Music Room or Ladies’ Withdrawing Room, and it seemed to indicate the place of the house in this world. A pianoforte stood here, of that wood which in old age seems to resemble polished tortoise-shell. There was silver of age and grace, and a view of the Hanging Chart from its north windows; Molly Farnleigh used it as a sitting-room. It was very warm and quiet here, except for the ticking of the clock.

What the Farnleighs are waiting for, though they don’t yet know it, is foul murder, a hint of the supernatural, Satanic cults, possible robot killers (in 1938), and a killer whose lack of genius almost overwhelms the brilliance and eccentricity of Dr. Gideon Fell’s efforts to unravel the mystery.

But pause a moment to admire the literary skill in this little scene at the start of Chapter Two of The Crooked Hinge, a classic Carr mystery. It not only established Farnleigh Close, which is both the setting and the McGuffin that seemingly sets the action in motion but it sets a mood. Chimney’s are “thin and close,†the woods are called Hanging Chart and shadowed ominously, the “silver of age and grace†lays over a room. A clock ticks at the beginning of the paragraph and is brought in again at the end, establishing a tension. Something is coming. Something sinister though nothing concrete has been said to tell us that.

Carr does this effortlessly, his use of metaphor and simile as sharp as Chandler, though applied to a different end.

Even the title, The Crooked Hinge, suggests something sinister about a house, something not quite right about it or the people in it.

The setting is Kent, where John Farnleigh (“The old-time Farnleighs were an unpleasant lot…â€), a survivor of the Titanic lives with his wife in Farnleigh Close, but another claimant has shown up claiming to be the real John Farnleigh and an inquest is scheduled to establish the truth. Carr tries out his own solution to the famous Tichborne Claimant case.

Then the first Farnleigh is murdered by the pool, his throat slashed in front of three witnesses, and none of them saw anyone do it and the police can’t find the weapon.

Is it the automaton modeled on Maezel’s Chess Player that reaches out to touch a maid and nearly frightens her to death, and who stole the thumbograph, a device for taking fingerprints, not to mention the suggestion of a cult of Satanists. DCI Elliot (…â€youngish, raw-boned, sandy-haired, and serious-minded. He liked argument, and he liked subtleties…â€) investigates and calls on Dr. Fell to sort out the sinister goings on, as he points out:

“Our problem is who killed Sir John Farnleigh.â€

“Quite. You still don’t perceive the double-alley of hell into which that leads us. I am worried about this case, because all rules have been violated. All rules have been violated because the wrong man had been chosen for a victim…â€

A ranking of the top ten impossible crime mysteries of all time placed this one number four. It is Fell and Carr at their considerable best. It is dedicated to Dorothy L. Sayers.

Just why the wrong man was murdered becomes as important as how. Fell cannot quite lay hands on why the murderer struck and why he has not struck again: “This murder is human, my lad. I’m not, you understand, praising the murderer for this sporting restraint and good manners in refraining from killing people. But, my God, Elliot, the people who have gone in danger from the first! Betty Harbottle might have been killed. A certain lady we know of might have been killed. For a certain man’s safety I’ve had apprehensions from the start. And not one of ’em has been touched. Is it vanity? Or what?â€

In finding the solution Fell even calls on S. S. Van Dine and Philo Vance’s favorite work, Criminal Investigations: a Practical Textbook by Hans Gross (The Bishop Murder Case) to explain the esoteric but quite real murder weapon (and true to Carr he has laid the groundwork for the killer’s expertise with the weapon) and in a real twist reveal the killer twice in a single chapter.

The Crooked Hinge is Carr and Fell at their best. The mystery sparkles with hints of something unhealthy and outside the realm of the possible, with Fell at his eccentric, high handed, and deceptive finest, and full of well-realized characters just the right side of cardboard, neither overwhelming the story nor mere cut-outs to be moved on the board.

This is a model for the genre, especially that special corner of impossible crime and hints of something sinister and beyond that John Dickson Carr made his own.

November 21st, 2022 at 8:14 am

I believe this may be the list referred to placing Crooked Hinge at #4.

https://mysteryfile.com/Locked_Rooms/Library.html

November 21st, 2022 at 10:20 am

It is indeed!

November 21st, 2022 at 1:52 pm

And for those keeping score at home, this book also appears in the list 13 BEST NON-SUPERNATURAL HORROR NOVELS selected by Karl Edward Wagner in June 1983 issue of Twilight Zone Magazine.

November 21st, 2022 at 11:09 pm

And of course Carr’s THE BURNING COURT made the Wagner list of 13 BEST SUPERNATURAL HORROR NOVELS.