Tue 14 Feb 2023

A PI Mystery Review by David Vineyard: T. C. H. JACOBS – The Red Eyes of Kali.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[6] Comments

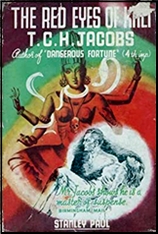

T. C. H. JACOBS – The Red Eyes of Kali. Temple Fortune #2. Stanley Paul & Co., Ltd., hardcover, 1950. No US edition.

Chief Inspector Barnard in particular looks forward to the day Fortune steps over the line, and of course there wouldn’t be a book if this wasn’t the time Fortune and his associate Sailor Milligan took that step while trying to protect attractive client American Julie Somerset and recover the rubies of the title, the red eyes of Kali (colorful story about their origin in Burma included, but no curses).

Breathless is how the jacket copy describes it, and it is a fair description of this book and most of the British thriller genre. Here there is even a little bit of scientific detection thrown into the mix as Fortune struggles against the police and on the other side of the game his first suspect, Leon Markovitch, who mistaking Fortune for a gentleman thief tries to hire him to steal the jewels from Julie Somerset’s father.

With a name like Leon Markovitch in the hands of any British thriller writer but John Creasey you know he is up to no good.

The easy way out being closed, Fortune now finds himself at odds with two known elements and a third yet to be discovered, never a bad set up to keep the action moving which is the prime reason for the thriller genre.

This is the second Temple Fortune novel, after Dangerous Fortune (luckily Jacobs gave up early on all the titles having Fortune in the title), and the beginning of Jacobs’ association with his most popular creation. Jacobs began writing in the Thirties, mostly about Chief Inspector Barnard and Detective Superintendent John Bellamy, who appeared in nineteen novels between 1930 and 1947. And yes, it is the same Barnard, a bit of an oddity as if Leslie Charteris had written a series of Claude Eustace Teal novels along with the Saint (though Barnard still gets a few chapters to shine). 1948 saw the birth of Fortune, Jacobs most successful creation, but far from his last.

Jacobs was one of those prolific British thriller writers, virtually unknown on this side of the Atlantic, but who had a long career in popular fiction (his last book was released in 1974) in multiple genres. Aside from Jacobs he also wrote the Slade McGinty books under his own name Jacques Pendower, twenty three of them between 1955 and 1974, and books about Mike Seton and Jim Malone as Jacobs, romance novels as Pam Dower, Marilyn Pender, Anne Penn, and Kathleen Carstairs, and Westerns as Tom Curtis. Most of his later books are sub-Bondian spy novels.

Along the way he found time to write three true crime books and a radio play based on his own novel.

Temple Fortune is a private eye, but in name only. He’s basically the gentleman adventurer a la the Toff or Norman Conquest dressed up with an office and clients instead of stumbling into adventure. He has little relationship to his American cousins ,or for that matter to Peter Cheyney’s slightly shady tough guys or David Hume’s Mick Cardby. Fortune is the type the forelock tugging classes call “guv†and his friend Sailor tends to say “Sink me…†fairly often when taken aback.

Sailor is mostly there as semi comic relief and to give Fortune someone to explain to while once in a while lending a helping fist when needed, the role of good sidekicks from the earliest days of the genre, violent, but not overly smart.

This is the kind of book with characters called Hambly Hogban, Freddy Flack, a Chinese thug named Charlie Yeo, and the Honorable Charles Falconridge referred too once to often as the Hon. Charles.

While not bad, Jacobs really doesn’t deserve reviving. There is some historical importance as the Fortune and Pendower books demonstrate how the British thriller was changing in the Post War era. Jacobs managed to ring enough changes on his writing over the years to graduate from minor Edgar Wallace imitation to the Peter Cheyney era and eventually a curious mix of the first two with a little James Bond thrown in. The Fortune stories tend to be detective stories and the McGinty’s spy novels.

He wasn’t unique in evolving with the times, but he did it well enough to survive and prosper over the years, no mean talent. Broken Alibi, a Bellamy novel, based on the Brighton Trunk murders from 1957, is a good one if you are interested, or 1954’s Good-Night, Sailor with Fortune.

February 14th, 2023 at 9:10 pm

I read the title, and you had me, right then and there.

February 15th, 2023 at 3:22 pm

T. C. H. Jacobs was one of the contributors to the early EDGAR WALLACE MYSTERY MAGAZINE, sending me “True Crime” articles and short stories. At 19 I was very much the “boy editor” while Jacobs was the “seasoned man”. I can remember he was one of a number of UK crime fiction figures particularly supportive when Nigel Morland usurped my role. (Jacobs cast doubts on Morland’s several claims, including that of close friendship with Wallace.) More can be found about Jacobs at http://blackhorsewesterns.com/bhe5/ in the article “Detectives in Cowboy Boots”.

February 15th, 2023 at 4:41 pm

Thanks for the link, Keith. Neat that you once actually had lunch with Mr Jacobs, maybe more than once? I love learning about personal connections like that!

February 15th, 2023 at 6:42 pm

Thanks Keith.

I hope I wasn’t too hard on Jacobs, he was a highly successful author for good reason in his time, I just didn’t feel there was anything special there other than the considerable skill to keep a writing career going from 1930 to 1974.

February 15th, 2023 at 8:17 pm

In the later years, David, that was indeed a considerable skill, especially in the UK! I don’t know if it has been mentioned elsewhere before, but in the 1960s, Jacobs also supplemented his income writing scripts for the uniquely British 64-page western and war comic-book “libraries”. When I moved on to Odhams, I also recruited him to write stories for boys’ adventure annuals. Jacobs was versatile and hardworking.

February 16th, 2023 at 9:38 pm

For fans of the British thriller genre like me Jacobs is worth getting to know, he handles it quite well, and the Fortune books are popular enough one of them even got the SUPER DETECTIVE LIBRARY treatment of a digest sized full comic book adaptation.

For the more casual reader Jacobs is probably more interesting for his longevity and ability to ride the tides of popular fiction over so long a period.

Forty four years across the Depression, the War, and the Post War era into the new age is an impressive run for anyone writing popular fiction, rivaling better known writers like Charteris, Creasey, and Gray in a dynamic genre that often went through careers fairly fast.

He survived the Edgar Wallace era, the Cheyney era, the gentleman adventurer, the private eye, and the spy era without seeming to struggle and as Keith points out expanded into other markets to supplement those when most writers are struggling just to keep up.