Wed 10 May 2023

A Mystery Review by Tony Baer: CORNELL WOOLRICH – Hotel Room.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[11] Comments

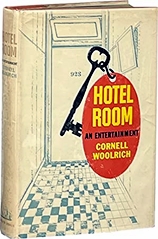

CORNELL WOOLRICH – Hotel Room. Random House, hardcover, 1958. No paperback edition.

The novel’s protagonist is Room 923 of the St. Anselm Hotel in New York City.

A nice, fresh, new and sparking hotel, the room was christened June 20, 1896, by newlyweds.

Crossing the threshold, the bride tells the groom, on the inevitability of aging, ‘I can’t imagine it ever happening to me. But when it does, it won’t be me any more. It’ll be somebody else….. An old lady looking out of my eyes… A stranger inside of me. She won’t know me, and I won’t know her.’

‘Then I’ll be a stranger too,’ responds the groom. ‘Two strangers, in a marriage that was begun by two somebody-elses.’ He closed the door. But for a minute or two his face seemed to glow there where it had been. Then it slowly wore thin, and the light it had made went away. Like the illusion of love itself does.

Down the bride’s face, “a thin shining line down each cheek like silver threads unraveling from her eyes. ‘Don’t let the day come. Don’t let it come yet. Wait till he’s back first’… mercilessly the night thinned away, as if there were a giant unseen blackboard eraser at work, rubbing it out. ‘But now tomorrow’s yesterday…. Oh, what happened to tomorrow? Who took it away?’

Next we are catapulted in time to the day Wilson declares war against Germany, April 6th, 1917. A young enlisted man comes, seeking a room on his last night. Everything’s booked. But an elderly German couple are in 923. Screw the krauts, screw the Kaiser, says the desk-man. And kicks them out. It’s the patriotic thing to do. Everyone “broke out in a rash of patriotism, like hives.â€

The young enlisted man calls a pretty girl he knows just vaguely and needles her into a date. He pressures her into giving herself to him. It’s the patriotic thing to do. And she does. Fervently. Oh what passion. What patriotic passion. And they immediately afterwards run out and wed. Promising not to speak to each other again until the war is over. And that day meeting again. At Room 923.

Now it is Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. And the clandestine couple meets again. And they don’t recognize each other. The patriotic passion is spent. They don’t really care for each other at all. And they agree to an annulment. To let it go.

And now it’s February 17, 1924. The last night in the life of a Mafioso who has lost his grip. Who has lost his hold on his territory. He’s done but doesn’t know it.

His mother comes to see him. “’D’you remember when I was a kid, and you used to make lasagne for Vito and me, and bring ’em hot to the table—?”

‘Quella non ero io . . .That was not I, that was another woman, long gone now. A woman whose prayers were not answered. Io non sono piu tua madre . . .’ she whispered smolderingly. ‘Mother, no. Just a woman who bore a devil. The woman who once bore you says good-bye to you.’

And then there was death, the great know-nothing part of life. Or had life perhaps been only the brief knowsomething part of an endless all-encompassing death?â€

The next time we come to Room 923, it is the evening of the stock market crash, October 24, 1929. And the man checking in, a powerful Wall Street man. At least he was so that morning. And now he’s squat.

The hotel’s become second rate, with time. “’[N]ever been in a hotel like this before…. Oh, not for a long time, anyway, And that was another me… My life slipped out of its room and beat its bill, and there are no tracers anywhere that can find it and bring it back.’

The bellboy performed all the little flourishes, turning the light behind it on, then off again, shed a spark for an instant, and then remain out as it had been before.

He looks at a photo of his daughter, inscribed: “’To Daddy from his loving Ruth’. And there was something so polite….. greetings from a distance, from a thousand heartbeats away, from which all the warmth has escaped en route, they had so far to go.â€

Opening the window to jump out, “Like an extra dimension, that had been lurking about him all the while, but whose existence he had never suspected until just now….. glass behind which all life is supposed to be lived, to be allowed to run its course, unknowing — he knew now — of the strangeness on the other side. The glass that, without that, shatters easily enoughâ€.

Next is the night before Pearl Harbor, December 6, 1941. A mixed couple, a Caucasian girl and a Japanese boy, have run away together to NYC—to escape the anti-miscegenation racism of their parents. To start on their own. To elope. And begin their lives……

And last, we are left on September 30, 1957. The evening before the demolition. The hotel to be razed for an office tower.

The blushing bride we met back in 1896 has come back. To bookend her life, and the life of the room.

She thanks her departed husband “for not slowly aging before my eyes, as I would have slowly aged before yours, until finally neither of us was what the other had married, but somebody else entirely. Some unknown old man. Some unknown old woman. Thank you for staying young. And for letting me stay young along with you. A lifetime of youth. Eternal spring.â€

’[H]otel rooms,’ amended the maid, ‘are a lot like people.’”

I liked it. A bit wistful and sad, with dominant sense of geography and loss. It’s an interesting idea for a novel: having the location as the main character, letting the setting stay still, slowly aging, and having the times and people change, in accelerated action at momentous times. It would make a good play.

I’ve often felt the strange gap where you visit a familiar place, a house you grew up in, or a town, a restaurant, great memories, so intensely real, but gone and gone forever. And the place remains, seemingly unscathed.

But is it? Is the place unscathed? Or are all of the memories and events somehow contained therein? Redeemable in time?

I don’t have any of the answers. And neither does the novel. But there are evocations and suggestions of meaning. Which is the only honest response anyway.

Woolrich dedicated the novel to his dear mother, his roommate until the end:

To Claire Attalie Woolrich

1874-1957

In Memoriam

This Book: Our Book

Woolrich also wrote at least a couple of other stories taking place at the St. Anselm Hotel. One of the stories, “The Penny-A-Worder,” also takes place in room 923, and is about a pulp mystery writer assigned a rush order to write a cover story to match a cover that has already been produced — set to go to the printers tomorrow morning. This story was intended to be included in Hotel Room — but the publishers decided that it didn’t fit in with the rest of the stories.

“Mystery in Room 913,” written twenty years earlier, occurs right down the hall. It’s a pretty typical, but well-told story about a mysterious ‘suicide room’. Every single man who checks in seems compelled to throw himself thru the window. The cops buy it. Why complicate things? It’s the depression! But the hotel dick doesn’t believe it at all. And he uses himself as bait!

—–

Barry Malzberg , Woolrich’s last agent, set me onto Hotel Room with his recommendation of ‘The Penny-A-Worder’. But I’d suggest to readers to save that story until after reading Hotel Room. It has just the right dream within a dream quality that gives the rest of the book its intended phantasmic effect. And it should have, to my mind, have been included as an epilogue to the book.

Malzberg, in a reminiscence contained in The Big Book of Noir, edited by Ed Gorman, Lee Server, and Martin H. Greenberg, recalls complimenting Woolrich on Phantom Lady. Woolrich’s response was that the man who wrote that novel has been dead for years.

It’s an interesting take on life. That the person that you are and the person that you were are strangers to one another. It’s a dissociation shared by all of the characters in Hotel Room. You could retitle the title: ‘In Memoriam to Identity’ (to steal from Kathy Acker), or, to coin a phrase: ‘The Dissociation Association’. But perhaps Hotel Room is right. It’s anonymous. And it fits you. At affordable rates. It may even be a vacant now. Make your reservation. Room 923 awaits.

May 10th, 2023 at 6:09 pm

Woolrich often wrote fixups, shorts or novellas tied up by some coincidence like a cursed jewel or a hotel room that fit quite well as not quite just an anthology usually with new transition material and a few changes from the original printing that tied the stories together, though I don’t know this is the case here.

THE DOOM STONE is one that comes to mind.

This seems a more natural fit and I can’t help but wonder if Stephen King might have read this before his book about a cursed hotel room.

The idea of an event or location tying disparate stories together wasn’t new in literature, but Woolrich notably puts a twist on it.

May 10th, 2023 at 6:14 pm

Perhaps the most melancholy — and fascinating — novel (or connected story collection) I’ve ever read. Quintessential Woolrich toward the end of his long melancholy — and fascinating — writing career.

May 10th, 2023 at 11:25 pm

Fine informative review. I also read The Penny-A-Worder based on Mr. Malzberg’s recommendation. Good story.

May 11th, 2023 at 4:42 am

From what I have read from Francis M Nevins, Woolrich’s own apartment could have served as the inspiration for this.

May 11th, 2023 at 4:41 pm

Doesn’t Woolrich’s HOTEL ROOM (“interesting story about the events that happen in room 923 of the same hotel over a span of many yearsâ€) sound a lot like David Lynch’s HBO 1993 cable film HOTEL ROOM (“[t]he lives of several people spanning from 1936 to 1993 are chronicled during their overnight stay at a New York City hotel roomâ€)?

May 11th, 2023 at 5:09 pm

The concept’s the same, but David Lynch’s stories bear no resemblance to Woolrich’s. Pure Lynch, you might say. Another HBO series with the same general idea is ROOM 104. What I don’t know is whether either project was “inspired” by Woolrich’s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Room_104

May 11th, 2023 at 6:49 pm

Mystery in Room 913 is extraordinary.

Please don’t miss it.

May 11th, 2023 at 11:44 pm

First published in Detective Fiction Weekly June 4 1938.

Currently available on Kindle. But alas, I don’t remember ever reading it. I think I should!

May 12th, 2023 at 6:28 am

Mystery in 913 is quite good up to the denouement. But like many mysteries of the era, that’s where it lost me. The ‘scientific’ explanation for the suicides was barely plausible and not very convincing. And there are charts, for gods sakes. Charts!

May 14th, 2023 at 1:57 pm

Strangest thing, by me, is that no one has reprinted it since. Wonder if Hard Case will get interested thus, or Greg Shepard at Stark House.

May 14th, 2023 at 2:53 pm

Todd,

No physical edition since then, but there is an ebook version available:

https://www.amazon.com/Hotel-room-Cornell-Woolrich/dp/B0007E86I2