Thu 20 Jul 2023

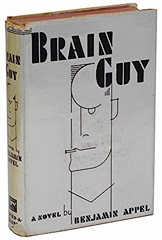

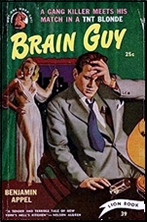

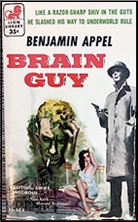

BENJAMIN APPEL – Brain Guy. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1934. Lion #39, paperback, 1950. Lion Library #151, paperback, 1957. Also published as The Enforcer (Belmont Tower, paperback, 1972). Stark House Press, softcover, 2005 (two-in-one edition with Plunder).

The first in a trilogy (Brain Guy, The Power-House, and The Dark Stain) about the rise of a mob boss (Bill Trent) from Hell’s Kitchen.

We start with Bill as a rent collector for a real estate agent. There’s a wink and a nod for the tenants with speakeasies and brothels, but you better not get caught by the cops. If you do, the agent will play dumb, blame it on the collector, and can them on the spot. Which happens to Bill.

Now Bill is broke in the Depression, like everybody else. But he’s not like everybody else. He’s not gonna beg. He’s not gonna starve. He fancies he’s a Brain Guy. A guy with schemes.

So he sells his schemes to one of the mobsters he used to collect the rent from. The scheme is this: Bill collected rent from all the stores in the neighborhood: the dress store, the meat store, the cheese store, the speaks. He knows when they’ve got their dough on hand. He knows just when to hit them.

So that’s how he gets his start. Robbing all the tenants he used to rent collect.

He hooks up with some muscle, takes a whore for his moll, and kills his way to the top.

What’s a bit unique about the story is that we see all the self-doubt of Bill Trent. He nearly fails many times. He nearly gives up. He’s just playing by ear and he has no idea what he’s doing. He is fully conscious that all mob bosses are employees at will, their time is grossly indeterminate, and the termination notice is terminal. He’s just a guy filling a role: Brain Guy. And he’ll keep it til he gets knocked off by the next one. And so on.

The story is nothing new, really. But it’s a well-done, credible, three dimensional picture of how a pretty ordinary guy becomes a monster. Never a monster in his mind. But in his actions. Always just doing what thinks he has to do to survive.

There’s a nice quote on the cover from the New York Times saying it’s “written with the cold, corroding passion of one who has seen through the heart of human poverty and degradation and had all the softness and sham burned away.†Which seems to me as good a definition as any of hard-boiled prose. What was happening in the Poisonville’s of America during prohibition and the depression produced pockets of desperation. And desperation speaks with concision.

When death is imminent, you don’t tend to use a lot of pretty adverbs and adjectives. You cut to the chase. Bullshit has a way of disappearing down the mouth of a gun. In Fight Club, there’s a scene where Tyler Durden holds up a convenience store cashier:

Tyler: What did you wanna be Raymond K. Hessel? The question, Raymond, was: What did you want to be!

Raymond K. Hessel: Veterinarian, veterinarian.

Tyler: That means you have to get more schooling.

Raymond K. Hessel: Too much school.

Tyler: Would you rather be dead?! Would you rather die? Here, on your knees in the back of a convenience store?

Raymond K. Hessel: No, please no!

Tyler: I’m keeping your license. I’m gonna check in on you. I know where you live. If you’re not on your way to becoming a veterinarian in six weeks you will be dead! Now run on home.

[Raymond gets up and runs into the night.]

Tyler: Tomorrow will be the most beautiful day of Raymond K. Hessel’s life. His breakfast will taste better than any meal you and I have ever tasted.

Heidegger talks of ‘being towards death’ — that only the constant thought of mortality keeps us authentic. Keeps us from collapsing into the idiot wind of idle chatter. Adorno says ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’. But my favorite formulation of the hard-boiled manner comes from The Misfit in Flannery O’Connor’s A Good Man is Hard to Find: “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

So there you have it. The book feels real. With hard-boiled patter. The better to think with. The better to speak with. The better to be authentic in the life you live.

July 20th, 2023 at 7:30 pm

I’ve never read this one, even though I’ve owned copies of the two Lion reprints off and on over the years. They always looked like schlock to me. The title didn’t help all that much, either. It’s good to know what it’s really about and that there’s more to the book than I realized.

July 20th, 2023 at 8:35 pm

Lack of authenticity can kill a book like this. Go a touch too poetic, let the violence become cartoonish, be a shade to sympathetic about you main character…

Appel is too good a writer for that and it shows here.

July 21st, 2023 at 3:22 pm

I like that first paragraph of yours, David. You could build a good working definition of the word “schlock” out of it.