Tue 27 Feb 2024

MOVIE! MOVIE! Reviewed by Dan Stumpf: Two Films by W. C. Fields.

Posted by Steve under Films: Comedy/Musicals , Reviews[5] Comments

Two Films by W. C. Fields.

THE FATAL GLASS OF BEER. Paramount, 1933. With W.C. Fields, Rosemary Theby, George Chandler and Gordon Douglas. Produced by Mack Sennett. Written by W.C. Fields. Directed by Clyde Bruckman.

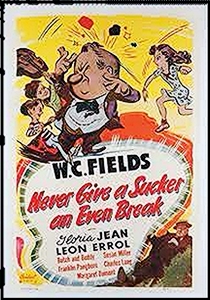

NEVER GIVE A SUCKER AN EVEN BREAK. Universal, 1941. With W.C. Fields, Gloria Jean, Leon Errol, Margaret Dumont, Franklin Pangborn, Anne Nagel (as “Madame Gorgeous”) Minerva Urecal, Carlotta Monti, and Emil Van Horn (as “Gargo the Gorilla”) Written by John T. Neville, Prescott Chaplin, and “Otis Criblecoblis.” Directed by Edward Cline.

Genius strikes twice, near the beginning and shortly before the end, of W C Fields’ career in talking pictures.

Fields was a confirmed star in silent movies, but studio heads must have been nervous about his fitness for sound, because early on, Paramount featured him mostly in their “All Star” features, co-billed with players like Burns & Allen, Charlie Ruggles, and even Bela Lugosi and Gary Cooper!

But at the same time, Fields was working on ultra-low-budget shorts for Mack Sennett, mostly recreations of his old Vaudeville routines, and among these mini-films, Fatal Glass of Beer calls out to this discerning critic, with its stunning location photography, stirring music, heart-wrenching drama, breath-taking special effects, and thematic resonance, contrasting man’s struggle with the elements and his struggle against sin, for a deeply-felt statement about the savagery of both.

We-ell, that may be stretching things just a bit.

The location photography is actually grainy old stock footage with mis-matched sound effects. The music is written & performed by Fields himself (“Mind if I play with my mittens on?”) and the special effects are only astonishing in their audacious ersatzery, so obviously fake as to evoke gasps of disbelief in the audience.

In fact, what we have here is Fields testing the notion of what it is to be a movie. He deliberately calls attention to the language of film-making, just to craft cinematic puns with it, and the drama creaks with age, played with stony seriousness by a cast of seasoned pros acting like amateurs. The result is a film as anarchistic — and as funny — as Duck Soup or Airplane, hacked out by a genius fluid in the language of Cinema.

Eight years later we find W.C. Fields physically deteriorating in his last solo-starring feature film, Never Give a Sucker an Even Break, and once again we find him toying with the question, What does it mean to be a Movie? Artists and critics have asked What is a Painting? What is a Novel? A Statue? A Bird? A Plane? A Superman? (Well, only Shaw, Siegel & Schuster asked that last one, and really no critic worth his by-line bothers with birds & planes anymore.)

But I digress. With Never/Break, Fields threw together every element of a 1940s comedy, then tore them all apart. Once again, we get stunning locations — glass-painted courtesy of Universal Studio’s Jack Otterson (of The Killers and Son of Frankenstein). We get musical production numbers, some quite elaborate, and there’s even drama of sorts, but don’t try to summarize the plot, because there isn’t any, just a rickety framework about Fields trying to sell a story to his producer, a framework that quickly sinks into the story itself.

Ah yes. Where Fatal/Beer marches through melodrama, Never/Break tiptoes through the tulips of timeworn cliché, with predictable romantic rivalries, vapid young lovers, doting dotards and twinkle-eyed teenagers. And Margaret Dumont. And a Gorilla. And a wild chase for a finale that has nothing to do with the rest of the story. Like I said: every element of B-movie comedy broken down and packaged up like a celluloid Xanadu.

It’s seldom that a career is bookended so neatly. In fact, the closest I can recall is John Wayne going out with The Shootist. And let’s face it, Fatal Glass… wasn’t Fields’ first film, nor was Never Give his last. But they’re close enough — and memorable enough — to work for me.

February 27th, 2024 at 10:03 pm

Love it. Kudos.

By “all star features” I reckon you mean things like “International House” which were in themselves, wonders.

Next to catch my eye: “no critic worth his by-line bothers with birds and planes anymore”

…yea …except for the team responsible for the Boeing 737 MAX. Groan!

Anyway, always wunnerful to revisit Fields. Anything to upset the frumpish modern world where all coarseness and jocularity is practically outlawed.

Thinking over the great early comedians …might be no one more quintessentially an Emperor of Irreverence. Lenny Bruce, sure –but that was decades later.

Ah well. Give me W.C. any day (and TWICE in Philadelphia)

February 28th, 2024 at 7:52 am

“It ain’t a fit night out for man nor beast!”

A classic for sure.

NEVER GIVE A SUCKER is good, all right, but my favorite Fields film remains IT’S A GIFT, which I quote from regularly.

February 29th, 2024 at 3:24 pm

Same here on both counts (i.e., favorite and regularly quoted) for both me and my wife re: It’s a Gift. My #2 is The Man on the Flying Trapeze; generally prefer the earlier Paramount features to the later Universal ones.

March 2nd, 2024 at 12:07 am

Watching a film starring W. C. Fields and expecting anything other than W.C. Fields can be frustrating. I know many of the them do have plots, but not so you really care. It’s amazing he restrained himself so admirably in DAVID COPPERFIELD.

His mere presence is a kind of anarchy.

March 3rd, 2024 at 11:51 pm

“Filthy stuff, water”