Tue 19 Mar 2024

The Amazing Colossal Belgian: A Quartet of Christie Expansions Part 4: Remembered Death, by Matthew R. Bradley.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

A Quartet of Christie Expansions

Part 4: Remembered Death

by Matthew R. Bradley

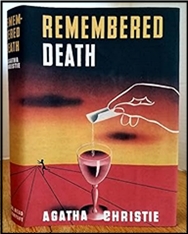

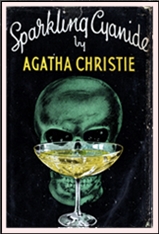

Agatha Christie’s revisions of her Hercule Poirot stories sometimes involved expansion into novels, sometimes involved exchanging one of her many sleuths for another…and, on one occasion, both. “Yellow Iris” (The Strand Magazine, July 1937; Hartford Courant, October 10, 1937, as “Poirot Wins Again”) was first collected in The Regatta Mystery and Other Stories (1939), and it later sprouted into Remembered Death (1945), originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post (July 15-September 2, 1944) and then published in the U.K. under Christie’s original title, Sparkling Cyanide. Making his final appearance, as the featured detective in that novel, is Colonel Johnnie (aka Johnny) Race.

Despite supplanting him there, Race had been Poirot’s good friend in Cards on the Table (1936) and Death on the Nile (1937), both of which were first serialized in The Saturday Evening Post (May 2-June 6, 1936 and May 15-July 3, 1937, respectively). Embodied by David Niven in the 1978 feature-film version of Nile, Race actually debuted solo in The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), first serialized in the London Evening News, in no fewer than fifty installments (November 29, 1923-January 28, 1924), as Anne the Adventurous. “Iris” was adapted for radio in 1937—by the author, adding the initial article “The” to the title—and 1943, and with David Suchet, in 1991, for Series 5 of Agatha Christie’s Poirot.

Late at night, Poirot receives an urgent call from an unknown woman, a summons to the Jardin des Cygnes, where he is warmly greeted by “fat Luigi.” Having been directed to the “table with yellow irises,” he observes that all others bear pink tulips, and finds it set for six but currently occupied only by his friend Anthony Chapell, who is surprised to see him and mournfully reports that his “favourite girl,” Pauline Weatherby, is dancing with someone else. Soon, they are joined by her; their host, her brother-in-law and guardian, rich American businessman Barton Russell; Lola Valdez, “the South American dancer in the new show at the Metropole,” and Stephen Carter, who is “in the diplomatic service.”

Poirot’s circumspect questions fail to reveal which of the ladies called him, while Barton says it is apt that he has taken the seat left open to honor his wife, Iris, poisoned in New York four years ago that night with the same five present. With the remains of a packet of cyanide found in her handbag, it was presumed a suicide, but Russell says he has long disbelieved it, certain she was murdered by one of those at the table. He leaves to confer with the dance band, and as they launch into the same song that was playing that night in New York, a waiter circles the table in the darkness surrounding the spotlight, filling their glasses with champagne; just as Russell returns, Pauline slumps over, dead the same way.

Finding nothing in her handbag, Poirot announces that there is no need to have everybody searched, and has Tony flip the packet from the pocket of Carter, who said that Lola “had rather a fancy for Barton…in New York”; Russell, in turn, asserts that Iris loved him, and was killed to avoid a scandal. But the ensuing “Resurrection of Pauline” is revealed to be part of Poirot’s plan to expose Russell, who posed as a waiter in the darkness, for a failed murder. Just as in “The Theft of the Royal Ruby” (aka “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”; 1960), Poirot had conspired with the “victim” to fake her own murder, having deduced that it was she who called, and whispered in her ear when the lights went down.

Poirot tells Russell, “I do not know…whether you killed your wife in the same way, or whether her suicide suggested the idea of this crime to you,” presumably to cover up his misappropriation of funds under his stewardship. Pauline elects not to prosecute Barton, who also dropped the half-empty packet into Carter’s pocket, and is advised by Poirot to “go quickly [but] be careful in the future.” Christie incorporates the lyrics to two original songs: “I’ve Forgotten You” (set to music for ITV’s Suchet adaptation), performed by a hypnotic black girl at Barton’s behest, and “There’s Nothing Like Love for Making You Miserable,” which ends the story as Tony and Pauline happily dance off to “Our Tune.”

Sparkling Cyanide was adapted for television as 1983 and 2003 telefilms and “Meurtre au champagne [Champagne Murder],” a 2013 Series 2 episode of the French Les Petits Meurtres d’Agatha Christie [The Little Murders of…]; for BBC Radio 4 in 2012; and in the Japanese manga album Chimunīzu-kan no himitsu (The Secret of Chimneys, 2006). The novel’s rough analogs are Barton Russell/George Barton, Iris/Rosemary, Pauline/Iris Marle, and Carter/rising M.P. Stephen Farraday. At the Luxembourg restaurant, one year after Rosemary’s death, they are joined by Lady Alexandra Farraday; George’s secretary, Ruth Lessing; and Anthony Browne, who has a “shadowy past and…suspicious present.”

Two couples sit at adjacent tables: Pedro Morales and his girlfriend, Christine Shannon, and Gerald Tollington and his fiancée, Patricia Brice-Woodworth. But before that fateful second dinner party, which begins halfway through the book, Christie devotes chapters to each of the six, explaining their backstories, relationships with Rosemary and/or motives to kill her. When their mother died, 17-year-old Iris went to live with her married sister, who’d inherited a fortune from her godfather, Viola’s failed suitor “Uncle” Paul Bennett; a week before Rosemary died, Iris had interrupted her—recovering from the flu to which her depression was attributed—writing Iris a letter, revealing that it would then go to her.

George suggests that Iris, who inherits on her 21st birthday or marriage, remain living at Elvaston Square and that her paternal aunt, Lucilla Drake (impoverished by the financial claims of black-sheep son Victor), join them to chaperon her in society. Six months later, in a trunk in the attic, Iris discovers Rosemary’s unsent letter to “Leopard,” the lover with whom she planned to go away. Iris believes that he must be either Farraday—said to be a possible future Prime Minister, whose influential in-laws, Lord and Lady Kidderminster, grudgingly let Sandra marry beneath her station—or globe-trotting Browne, unseen since Rosemary’s death, who abruptly reappears only one week after Iris had found that letter.

Tony cultivates Iris, and George, after cautioning her that “nobody seems to know much about the fellow,” begins behaving oddly, buying Little Priors, the Sussex summer house near the Farradays’ Fairhaven. At last, he admits receiving anonymous letters saying that Rosemary was murdered, and if so, it must have been by someone at the table. We learn of Victor planting—or nurturing?—in Ruth’s mind that George should have wed her, not Rosemary; of Browne’s dismay when Rosemary reveals that Victor had outed him as ex-con Tony Morelli, a dangerous secret; and of Stephen’s horror when Rosemary suggested that she and “Leopard” divorce their spouses and marry each other, destroying his career.

While intuiting that Rosemary had a lover, George was uncertain who, and now hopes to ask Race, invited to that first dinner yet unable to attend, his advice about the letters. He tells Sandra that—on a “nerve specialist’s” advice—he is arranging the second to get Iris, never the same since, back onto the metaphoric horse, but admitting her knowledge of the affair to Stephen, she says, correctly, “I think it’s a trap.” Shortly before they are to leave Sussex, Tony surprises Iris by asking her, for reasons she must take on trust, to “come up to London and marry me without telling anybody,” but scoffs at the notion of Rosemary’s being murdered; Tony also sees the arrival of Race, obliquely noting that they “had met.”

George recaps Rosemary’s death, just as in “Yellow Iris,” and admits buying Little Priors because he suspected that her lover was either Stephen or Tony; the latter’s name rings a bell with Race, who wonders what motivated the letters and agrees that, while everybody had a motive, George would be unlikely to rake it all up if he did it. Secretive about his plan, George asks Race, formerly of M.I.5, to attend, yet is warned, “These melodramatic ideas out of books don’t work.” So it seems as Christie takes a hard left and George, who had Ruth deputize Buenos Aires agent Alexander Ogilvie to pay off for embezzler Victor, keels over after toasting, “To Rosemary, for remembrance,” this time sans resurrection…

Race saw nothing suspicious from his table some distance away, and compares notes with Chief Inspector Kemp (who had worked under Superintendent Battle, another second-tier sleuth in Cards on the Table), agreeing that this confirms George’s suspicions. Iris enters as Race interviews Lucilla, announcing her plan to marry Tony, then privately shows him Rosemary’s letter, certain now that “Leopard” was Stephen and she a suicide. Race’s old friend Mrs. Rees-Talbot is the new employer of Barton’s ex-parlourmaid, Betty Archdale, who reports overhearing Tony warn Rosemary she could be disfigured or “bumped off” if she spoke of “Morelli,” a convicted saboteur whom Race realizes is an undercover agent.

Reading of George’s death, actress Chloe Elizabeth West visits Kemp, saying she’d been hired by him to fill the empty seat—coiffed, dressed, and made up like Rosemary—until a call from someone cancelled it; confronted by Kemp about their affair, Stephen insists Sandra knew nothing. A scared Iris tells Tony that in the aftermath, she found planted in her handbag, and ditched under the table, an empty cyanide packet, and he convinces her to fess up to Kemp. After two failed attempts on Iris’s life, both revealed to be the work of Ruth, Tony identifies her as the true target of the second murder, intended to be taken as another suicide, but through a mix-up, George drank from Iris’s glass instead and died.

“Pedro” was Victor, who posed as a waiter while ostensibly making a phone call, and had conspired with Ruth, knowing that if Iris died unwed, her money would go to ever-pliable Lucilla. Christie’s acorn-into-oak job is superb, with the additional suspects and motives well drawn, as are secondary characters such as Lucilla, whose willful self-delusion about Victor is at once amusing and tragic. My only criticism is with the novel’s structure, as it moves backward and forward so often, before and after Rosemay’s death, as to leave this reader (and summarizer) occasionally uncertain as to where he was in that time sequence, a minor quibble in a work that I thoroughly enjoyed, however much I missed Papa Poirot.

— Copyright © 2024 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Editions cited:

“Yellow Iris” in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories: William Morrow (2013)

Remembered Death: Pocket (1947)

March 20th, 2024 at 7:12 pm

“…“Yellow Iris” (The Strand Magazine, July 1937; Hartford Courant, October 10, 1937, as “Poirot Wins Again”)”

Don’t know how interesting a story it might be, but this sentence intrigued me. How was it, I wonder, that a local newspaper for the Hartford was apparently where “Yellow Iris” was first published in the US?

It was BTW the very same newspaper that published my column of mystery reviews in the 1970s. (The column was called THE COURANT CORONER.)

Coincidence? I think not.

March 23rd, 2024 at 12:26 am

How writers cannibalize their own work from shorts to novels is always an interesting study of what is lost and gained.

March 27th, 2024 at 7:34 am

Steve: I, too, was intrigued by that question, and although unable to provide an answer (I thought I remembered seeing references to at least one other Christie story that made its U.S. debut therein, but cannot nail it down at the moment), I can continue the “local boy makes good” (?) motif, since the Courant was my local paper during my four years at Trinity College.

David: Indeed, that was the partial impetus for these posts. Would love to do more on Papa Poirot, and perhaps will someday, but right now my plate is too full. Thanks for reading.