Fri 12 Sep 2025

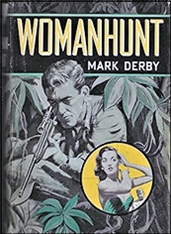

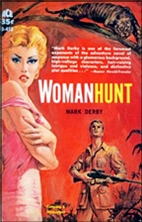

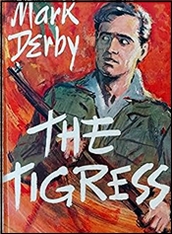

MARK DERBY – Womanhunt. Viking, hardcover, 1959. Ace D-458, paperback, 1960. First published in the UK as Tigress (Collins, 1959).

Dickson was tired and ready to retire from intelligence, but he had one more job to do in Malaya. It might even be pleasant, get a little tiger hunting in along the way. All he had to do was determine if Anna, a fellow agent and the woman he loved, was a traitor, and if she was kill her and her contact. For added pleasure he could take on a clever and dangerous Communist insurgent and save Malaya from falling into the Soviet orbit.

An “easy one. Just keeping an eye,” Landsdowne, his boss said, but it meant reconnecting with British publicist and writer Charlton Lang who Dix loathed, it meant looking at Anna as if she were a spy — and just maybe killing her and Lang too if it came to it, and it meant trailing far more dangerous prey than a man-eating tiger in the steamy jungles and more dangerous cities.

Mark Derby was one of the British thriller writers from the Golden Age of adventure fiction (roughly 1939 to 1980), the era that produced Hammond Innes, Geoffrey Household, Victor Canning, Alistair MacLean, Gavin Lyall, Jack Higgins, Desmond Bagley, and many more (all covered in Mike Ripley’s history of that period Kiss Kiss Bang Bang).

Derby, a former policeman and intelligence agent in the Far East was a lesser name in his native land, but sold extremely well in this country with books like The Sunlit Ambush, The Sun in the Hunter’s Eyes, and Afraid in the Dark doing well as book club picks and in paperback. He also did well with serializations and short stories in the Slicks, a far more lucrative market than hardcovers or paperbacks.

In the basics Derby most resembles Victor Canning though there is no imitation as such since almost all Derby’s work is set in his stomping grounds of the Far East. Like Canning his protagonists are often professional agents, though also like Canning, tend to come from the gentleman farmer class, countrymen familiar with rough country, well educated middle class Brits, clubbable, unlike say James Bond, but a bit rougher hewn and tougher than the upper classes. Like Canning’s heroes they believe in their work, but they are well aware of the bitter, cynical, and sometime ruthless nature and they have consciences that bother them (Canning himself changed with time coming to question if the “Game” needed to be played quiet as ruthlessly as it was).

In Derby’s case his history as a Colonial policeman and intelligence officer colors his view of the world, but in fairness it was the prevailing view of his time, and he does not write Yellow Peril or hysterical Colonialist fantasy. His Brits and his Asian characters are sympathetic or villain both, and he isn’t above sympathy for the devil so to speak. We’re a long way from Sapper and Sax Rohmer here, and simple assumptions about race and the “whiteman’s burden”.

Dickson has his hands full trying to determine which side Anne is on, negotiating the troubled politics of Malaya, hunting a tiger (this one literal) that proves more dangerous than he thought, and battling his own ethical and moral dilemmas before he brings his prey to ground in a fast moving and satisfying adventure thriller.

Of course the form has changed, and modern readers used to the hyperbolic widescreen style of Cussler, Berry, McNabb, or Rollins might find the more literary pleasures of the Golden Age writers a bit slow with their time out for local color, history, atmosphere, and culture and more complex heroes who tend not to wear their heroics on their chest and don’t always behave like overgrown Boy Scouts. Heroes. Villains in these tend to owe a debt to Eric Ambler and Graham Greene and the complexities of Robert Louis Stevenson’s heroes more than Doc Savage and Dime Novels.

Curious how a simpler and less aware time produced far more complex popular fiction asking far more serious questions than much of the genre today dares ask or even suggests.

September 12th, 2025 at 8:03 pm

I’ve not read anything by Mark Derby, and that sounds like an unwise neglact on my part. I have owned the paperback edition for quite a while now, the second image down, and I think everyone would agree it’s quite an attractive cover.

For anyone like me who’d like to know what else he wrote, here you are, thanks to the Fantastic Fiction website:

Novels

Afraid in the Dark (1951)

aka Malayan Rose

Element of Risk (1952)

The Big Water (1953)

aka Trail of Treason

The Bad Step (1954)

aka Out of Asia Alive

The Sunlit Ambush (1955)

Echo of a Bomb (1957)

Sun in the Hunter’s Eyes (1958)

The Tigress (1959)

aka Womanhunt

Ghost Blonde (1960)

aka Five Nights in Singapore

The Dark (1962)

September 12th, 2025 at 11:12 pm

Five Nights in Singapore was the basis of A Euro spy epic with Sean Flynn, Errol’s son, who went missing as a photo journalist in Vietnam.

September 13th, 2025 at 11:05 am

Thanks for an especially informative review. Now to seek more of his books…

September 13th, 2025 at 5:17 pm

I understood that the basis of Flynn’s film was “Cinq gars pour Singapour”, a novel by Frenchman Jean Bruce.

September 13th, 2025 at 9:12 pm

Johny, Looks like you’re right. The title of the film Sean Flynn was in is SINGAPORE, SINGAPORE, from 1967, based on a book by Jean Bruce.

September 14th, 2025 at 6:13 pm

The Flynn film is also known as Five Ashore in Singapore in some prints, my mistake.