Tue 7 Jun 2011

VICTOR MAXWELL (RE)REVEALED, by Terry Sanford.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Pulp Fiction[10] Comments

by Terry Sanford

When I began collecting pulp magazines over thirty years ago, I quickly zeroed in on Detective Fiction Weekly in all its various incarnations. I bought a lot of nice copies for fifteen dollars or less and I found a good number of stories that I enjoyed.

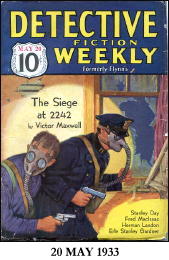

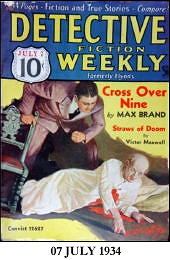

I soon realized that I was a fan of Victor Maxwell’s Sgt. Riordan and Det. Halloran stories, a police procedural series that began in 1925. I found these stories were amazingly modern. There were no rubber hoses, beatings or hours spent in a darkened room with a bright light in the suspect’s face.

Instead there were, just as there are today, instances where the interrogator lied to the suspect trying to extract a confession. The police were very concerned about their cases holding up in court and whether a smart defense attorney would shred them. (Riordan and Halloran are the two gents pictured here to the right and below, stalwart fellows both.)

As I began to collect all the stories, I began to see that there was little information about the author. The stories appeared almost exclusively in Detective Fiction Weekly, hereinafter DFW, and that magazine did often run an “About the author” feature, but Victor Maxwell was never included. Sometime, somewhere I read that the Maxwell name was thought to be a pseudonym.

About four years ago, I wrote an article for the Mystery*File website titled “Those Detective Fiction Weekly Mugs.” It was so titled because we added artist’s renderings of the various characters featured.

I wrote this to share my enthusiasm for the hobby and one of my favorite pulps. There was no thought of a reward. A year later, Steve Lewis, our editor and chief was contacted by Don Wilde, who is the step-grandson of the man who wrote as Victor Maxwell. Mr Wilde had googled the pen name and discovered the article.

Although he never met his grandfather he had some items that might be of interest. Steve kindly put the two of us together and we had a fine time sharing information. Within a few weeks, he sent me pictures, correspondence, three unpublished stories and two unpublished novel manuscripts and more. A treasure trove for a Victor Maxwell fan!

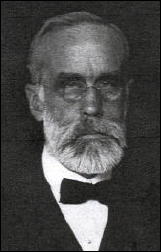

The identity of the author was never a secret. It was mentioned in almost all of his obituaries. It was simply lost over time. Victor Maxwell was a newspaper reporter named Maxwell Vietor.

Mr. Vietor was born on July 7, 1880 in New York City to Edward W. and Agnes C. (McCahey) Vietor. Edward Vietor was a medical doctor and within a few years, so was his wife. Edward was the founder of the Brooklyn Bird(watcher’s) Club, which exists today.

In January of 1882, Dr. Edward Vietor was summoned to a local residence where 10 year-old Bessie Thayer had become gravely ill after eating some candy she bought at the neighborhood candy store. Although Dr. Vietor was the third physician to see the girl that day, his was the correct diagnosis: arsenic poisoning! The girl died in his presence.

Dr. Vietor subsequently testified at a Coroner’s Inquest where it was resolved to turn the matter over to the police. There is no conclusion of the case that I’ve been able to find. Is it likely that this became a story that was mentioned from time to time in the Vietor household and fueled the imagination of young Maxwell? Perhaps.

At some point prior to 1910, the Vietors divorced. Dr. Agnes Vietor and Maxwell moved to the Boston area.

Maxwell graduated form Phillips Exeter Academy in 1898. He then attended MIT where the records show, “Maxwell Vietor ex.’02 has been granted a leave of absence for one year by the faculty, in order to take up practical railroad work with the Boston and Maine R.R.” Like many a college kid before him, Max soon realized that manual labor was not an ethnic gentleman.

According to several of his obituaries, he then returned to New York and began his newspaper career, first with the Sun and then with New York City News, a news distribution service.

Just prior to 1910, Max married Helena Haworth. The couple soon moved to Boston where Max continued as a reporter for The Boston Globe. By 1911, Max and Helena moved to the Vancouver, Washington and Portland, Oregon area.

That year Max made a haphazard attempt to keep a diary. Some of the entries deal with personal matters, but many of the pages just bore the letters, “P.P.” Finally months into the diary, those initials are spelled out: “Purple Pulp.” This was a humorous reference to his newspaper writing as he hadn’t yet begun to write for the real pulps.

Their only child, Alice was born on August 15, 1911. In 1915, tragedy struck the Vietor family. Helena’s car was discovered parked by a bridge spanning the Columbia river, but Helena was gone. The river flows into the Pacific ocean from that spot, which was used by many suicidal people over the years.

There was no trace of her after that day. Max would never remarry.

The January 20, 1916 issue of The Popular Magazine published the first Victor Maxwell short story, “The Little Girl Who Got Lost.” A second story appeared in August in that same pulp.

The family knew that Max occasionally wrote for the pulps full-time and one of those times may have been in 1917 when eight stories appeared in The Popular in an eight-month period.

Another minor mystery in Max’s life is evidenced by a letter found in his correspondence. The letter was from Ben W. Olcutt, Oregon’s governor and was dated April 5, 1920. The one-paragraph body reads:

“I am in receipt of your report of April 3rd, which I have read with much interest. In this connection and in passing I wish to say a good word for the work you have accomplished for the state in the capacity of special agent and for your highly intelligent and understandable report made in that connection.” There is no further explanation of his duties or service to Oregon.

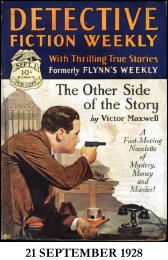

Reporting must have lured him back as the pulp stories ended until his first appearance in DFW in 1925. That story would be the first of exactly one hundred appearances in the detective pulps, thanks, in part, to a novelette that was serialized over three successive issues of DFW.

Max had found a home there. All but seven of his detective stories were published by DFW. What prompted the inquiry is lost to the ages, but in March of 1931, Max apparently wrote the editor of DFW asking if he thought the readers might be tiring of Riordan.

At this point Max had sold them over fifty stories in a five-and-a-half years. Editor Howard V. Bloomfield wrote Max saying that he did not think anyone was tired of Riordan and strongly encouraging to either continue with the series or send in even more!

In addition to the detective stories, Max wrote three non-fiction articles for DFW. There were a smattering of other stories published in The Popular, Railroad (&) Railroad Man’s Magazine, Short Stories and Street & Smith’s Complete Magazine.

And that and reporting was his life, along with raising his daughter. About 1938, Max moved back to the Boston area where his mother resided. He would finish his newspaper career at the Worcester Telegram–The Evening Gazette.

His hearing was going and he would be completely deaf before his death. He switched from reporting to editing copy and would communicate with his fellow employees via handwritten notes. His last pulp story was in the January, 1944 issue of New Detective Magazine.

In 1950, increasingly worse back pain was plaguing Max. He went to the Mayo Clinic finally for help. Their diagnosis was inoperable cancer. From the clinic, he returned to the Pacific coast to be with his daughter. Just two weeks prior to his death, there was a heart-breaking exchange of letters between Max and his employer where he was told he was not eligible for a pension from them.

He died at a Portland hospital of a heart attack on October 4, 1950, survived by his mother and daughter.

The stories and the novels I have in manuscript form are not publishable as they are. But it is one hell of a collection and I want to thank Don Wilde for his generosity of time and spirit. And thanks to Steve Lewis for starting the ball rolling.

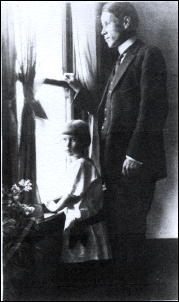

Note: The uppermost photo of Maxwell Vietor with his daughter Alice may have been taken in 1918. The date of the lower photograph is unknown.

June 7th, 2011 at 9:12 pm

Thanks for the invaluable information about Victor Maxwell. There is also a short biographical sketch about him in the January 5, 1929 issue of DFW. I haven’t looked at it yet to see if it gives much detail about him. Most of the DFW bio sketches didn’t reveal much about the authors.

Are any of the unpublished stories about Sgt. Riordan and his fellows? I have been enjoying the Maxwell stories in DFW for years, and still look forward to each new acquisition that contains one of his stories. I hope to write a series overview of the Riordan series at some point, but that will take quite a bit of work.

Monte Herridge

June 7th, 2011 at 9:19 pm

Fascinating!

June 7th, 2011 at 11:02 pm

An excellent piece of original research concerning one of the major DFW authors. Hopefully one day we will get to read Monte Herridge’s overview of the Riordan and Halloran series.

June 8th, 2011 at 9:05 am

Although the three short stories were aimed at the pulp market, there was not a Riordan in the bunch. The two novels were not aimed at that market and neither one is a mystery.

June 8th, 2011 at 10:30 am

Unfortunately, even though he wrote a lot of stories and was very popular at the time, Victor Maxwell isn’t a name that even many of the most dedicated pulp collectors recognize today.

To remedy that, wouldn’t be great if for some publisher were to put together a collection of some of the Riordan stories? I think so!

June 8th, 2011 at 9:19 pm

Terry,

Thanks much for a VERY interesting article about an author I’d probably never think of reading, but now I’ll try one or two of the Halloran/Roordan stories.

June 8th, 2011 at 9:59 pm

I would buy a book of Riordan stories. The problem is convincing a publisher to do such a book. I have already sent a request to Matt Moring of Altus Press for a book of Daffy Dill stories (by Richard Sale) from DFW. There are just too many good candidates for book publication of old pulp stories.

June 8th, 2011 at 11:31 pm

Matt Moring of Altus Press is just about our best bet to get some of these series reprinted. This year he hopes to collect all 44 of the Cardigan stories by Fred Nebel from DIME DETECTIVE. He also is working on a book collecting all the Donahue stories from BLACK MASK.

These are just two of the projects he is working on and I’m sure we will see many more in the future if we keep supporting his efforts.

July 24th, 2011 at 2:44 pm

[…] first part of this article on pulp writer Victor Maxwell appeared here earlier on this blog. As Monte Herridge pointed out in the comments that followed, there was a […]

January 4th, 2022 at 12:03 am

[…] immediately got Don in touch with Terry, and I’ll let Terry tell the tale from here. Or in fact he already has. (Follow the link, and you will learn […]