Wed 24 Jun 2009

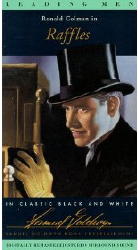

RAFFLES. Samuel Goldwyn, 1930. Ronald Colman, Kay Francis, Bramwell Fletcher, David Torrence, Alison Skipworth, Frederick Kerr. Based on the story collection (and the subsequent play based on it) The Amateur Cracksman (1899) by E. W. Hornung. Directors: Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast (uncredited); fired and replaced by George Fitzmaurice.

I had a strange experience while watching this movie, and of course I’m ready to tell you about it. Due to circumstances beyond my control, I watched this movie over the span of two successive evenings, even though it’s only a miserly 72 minutes long.

I’d enjoyed the first half immensely and was looking forward to the second half with considerable anticipation, only to find the second half a sorry letdown, and I for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why.

What had happened? Were they off budget and the production crew had to wrap things up too quickly? Scouring the Internet after the fact, it seems as though something like that did happen — as you will spotted yourself if you haven’t skimmed through the credits above too quickly.

A. J. Raffles, as you may know, is well-known even today as “The Amateur Cracksman,” quite fictional of course, and as a character, a gentleman burglar and house thief created by E. W. Hornung, who married a sister of Arthur Conan Doyle. The stories of his exploits were quite the rage in late Victorian England (approximately 1898 to 1905), but instead of my telling you more about them, I’d prefer to send to Mary Reed’s long and informative article about them, which you can find on the primary Mystery*File website.

In this first talking picture version of the Raffles stories, it is Ronald Colman, of the well-modulated British accent (and therefore a perfect choice in that regard) who plays the title character, and Bramwell Fletcher who plays his good friend and close associate, Bunny Manders. (Fletcher was last mentioned on this blog as one of the players in the The Mummy, which came out in 1932, but he was young enough to wind up his career in television in 1967.)

If my count is right, there were five earlier silent films with Raffles as a character. This 1930 version was followed by another in 1939, the one that starred David Niven, which I wish I could tell you that I’ve seen, but which I have to admit I have not. In spite of a good cast, however, including Olivia de Havilland, it does not seem to have gathered very good reviews.

But as you won’t have forgotten my saying so earlier, this earlier production showed a lot of promise. After proposing marriage to his lady friend Gwen (Kay Francis), Raffles promises himself an end to his career as a burglar, only to be confronted with Bunny’s gambling debts — a matter of some thousand pounds — with only a weekend between then and disaster.

So it’s off to the country and the Melrose mansion, which is also the home, not so coincidentally of the Melrose diamonds. And not only are Raffles and Bunny present, along with the usual assortment of house guests, but also a gang of lower class thieves with a Scotland Yard inspector hot on their trail, all of which are complications that Raffles had not counted on.

And when Gwen suddenly appears as well … and this is where I had to stop watching on the first evening.

To say that the next night’s continuing viewing proved disappointing is an understatement indeed. From a well-paced first half, an A-level production, the second half is a helter-skelter mish-mash of attempted break-in’s — some successful, some not — close calls, sudden shifts of scene, and gaps in the story line that a hansom cab could have plowed through easily.

There is one plus, though, that I would be remiss in not pointing out. Kay Francis’s character seems to light up from the slightly soporific to a lady with a mission and a delightful gleam in her eye when she deduces the truth about the man she’s promised her heart to. What a delightful adventure! she thinks (in those not-so-innocent pre-Code days).

And it should have been, and what’s more, it could have been, I’d like to believe, and I do.

June 24th, 2009 at 10:37 pm

Like you I was struck by how schizophrenic this film was when I first saw it. The Niven film is a little better, but still only minor. I’ve read that the John Barrymore silent was good, but only seen one brief scene — which was more active than anything in either of the talkie films. However, if you want to see Raffles done right check out the British television series with Anthony Valentine.

It aired here on A&E well after it’s initial run, but it is done with full style and charm. Raffles also shows up as a character in one of the films Christopher Lee and Patrick McNee did as Holmes and Watson, although I think played by a German actor.

And if you have read all the Hornung originals check out the pastiche Barry Perowne wrote. They are the rare pastiche that is actually superior in many ways to the original.

But be aware there are two series of Perowne’s Raffles stories, the first modern tales where Raffles is a Saint like gentleman adventurer that ran in the British magazine Thriller, and the second a critically praised series of short stories published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and collected in several books. The Thriller series is good, but the later EQMM series are among the best pastiche ever written.

Perowne (Philip Atkey) was the nephew of Bertram Atkey, whose own series of cracksman tales featured Smiler Bunn, and also ran in Thriller and were continued by Perowne. Guess it ran in the family.

Humorist John Kendrick Bangs contributed the adventures of Mrs. Raffles, and those of Raffles Holmes, the son of Sherlock and Raffles sister.

A novelization of the Valentine series by David Fletcher caused some controversy when it was published here as an original novel and later revealed to be an adaptation of the television series. Quite a few critics who had praised the book were upset to find they had heaped such praise on a novelization.

There is of course a famous article about Raffles by George Orwell that serves as the introduction to one collection of the Hornung stories.

Raffles wasn’t E.W. Hornung’s only contribution to the gentleman outlaw genre, and anyone who enjoys the Raffles tales should check out the stories collected in Stingaree and the William Wellman film of the book with Richard Dix, Irene Dunne, and Andy Devine about an Australian highwayman with a love of music. It’s a better film than either of the Raffles efforts and not a bad read.

June 26th, 2009 at 1:39 am

I remember reading the Perowne stories when they appeared in EQMM, but never the collections, which I don’t remember ever seeing. In fact, I don’t believe I even own a book by Barry Perowne, and I surely don’t understand why. (Note to myself. Fix this.)

Getting back to the EQMM stories, I really enjoyed them, not that I knew anything about Hornung’s stories, for I didn’t. I just thought they were pretty good for what they were.

Besides find a copy of the David Niven movie, you’ve also persuaded me track down the Anthony Valentine TV series. Apparently it’s out of print, but a few vendors have some of them for sale on Amazon. And probably elsewhere, for that matter.

June 26th, 2009 at 2:44 am

The Niven movie used to show up about twice a year on TCM, and A&E may have the Raffles series available through their video unit. These were well done adaptations of the Hornung stories.

There is also a play by Graham Greene, The Return of Raffles.

The Perowne stories were collected in, Raffles Revisited (1975), Raffles of the Albany (1976), and Raffles of the M.C.C.(1979). The last two published here by St. Martins. The books that appeared in Thriller are (in no order) Raffles Crime in Gibralter, Raffles in Pursuit, Raffles and the Key Man, Raffles After Dark, Raffles Under Sentence, and She Married Raffles (I don’t think any of them were published in the States).

Perowne’s other non series books of note include A Singular Conspiracy (about Poe), Rogue’s Island, and Gibralter Prisoner. Like his uncle Bertram Atkey Perowne was an Australian — not surprising considering Hornung’s ties to Australia,

The Hornung originals are worth discovering though some find them off putting. Raffles may be a charmer, but Hornung shows him warts and all despite Bunny’s hero worshiping. The three short story collections should be read and in the order they were written in if possible. I’m not as big a fan of the novel, Mr. Justice Raffles in which Raffles sets himself as a sort of judge, jury, and executioner of the underworld. Hornung’s The Crime Doctor is about a photographer and not the screens Dr. Ordway.

Many of Hornung’s Australian books are well worth reading. Stingaree which I mentioned, and Shadow of The Rope stand out among them.

And, of course, as everyone must know by now, Hornung was the brother in law of Conan Doyle and responsible for that famous doggerel: “Though he might be more humble/there’s no police like Holmes.” I assume Doyle was amused by that, he certainly wasn’t by Raffles.

The gimmick of the Perowne tales was that every story involved Raffles and Bunny with a famous historical or fictional character. The first story in the series picked up from Hornung’s last story having had Raffles killed in the Boer War. In Perowne’s story Raffles is only wounded, he and Bunny captured, and they escape by hijacking a train — which just happens to be the one Winston Churchill is escaping his capture on.

December 15th, 2014 at 12:49 am

The Niven film is a pass but Niven is so likable and perfect in the part it is easy to have wished a better opportunity for him. Updated to the second world war is an idea that may have seemed viable on paper but does not come off — Raffles is just not comfortable in his new period. The nearest, outside of Anthony Valentine’s television series with Christopher Strauli as Bunny, that captures the feel and time is not a Raffles story at all, but The Hour of Thirteen with Peter Lawford, based on Philip MacDonald’s novel X versus Rex, filmed earlier but to lesser effect in my opinion as The Mystery of Mr. X with Robert Montgomery in 1934. In the early fifties there was a proposed television series with George Brent and Nigel Bruce that never saw the light of day. Too bad about that.

May 5th, 2019 at 4:07 pm

You can get the Raffles A&E show through the library

March 8th, 2021 at 10:55 pm

George Orwell’s review of Raffles:

http://orwell.ru/library/reviews/chase/english/e_bland