Wed 16 Jun 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review: HENRY KANE – The Midnight Man.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[2] Comments

by Bill Pronzini:

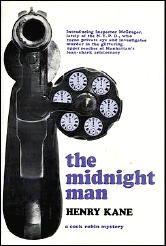

HENRY KANE – The Midnight Man. The Macmillan Co. (A Cock Robin Mystery), hardcover, 1965. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, September 1966. Paperback reprint: Raven House #9, 1981.

Henry Kane is best known as the creator of Peter Chambers, a tough but urbane New York “private richard” whose adventures were quite popular in the late Forties and throughout the Fifties.

(Some of the early Chambers short stories appeared in the sophisticated men’s magazine Esquire, which once devoted an editorial to Kane, calling him an “author, bon vivant, stoic, student, tramp, lawyer, philosopher … the lad who works off a hangover conceived in a Hoboken dive by swooshing down large orders of Eggs Benedict at the Waldorf on the morning after … the man who can use polysyllables on Third Avenue and certain ancient monosyllables on Park Avenue.”)

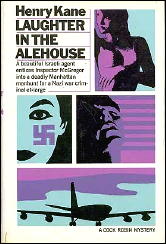

Kane wrote dozens of novels and scores of stories featuring the exploits of Peter Chambers; and yet, ironically enough, his most memorable private eye is not Chambers but a 250-pound ex-cop named McGregor. In fact, his three best mystery novels are those in which McGregor is featured — The Midnight Man, Conceal and Disguise (1966), and Laughter in the Alehouse (1968).

Like Chambers, McGregor is urbane, literate, and a connoisseur of beautiful women, gourmet food, and vintage booze. Unlike Chambers, he is prone to pithy literary quotes instead of suave wisecracks, and prefers to use wits and guile in place of guns and fists to solve his cases.

He is not a career PI with an office and a secretary; he is a newly retired New York City police inspector, “pushing fifty, ramrod-straight and robustly handsome,” known around headquarters as “the Old Man,” who dabbles at private investigation (he has a license, of course) just to keep a hand in.

He is more likable than Chambers, has more depth and sensitivity, and his three cases are less frivolous and more tightly plotted than any of the Chambers stories.

In The Midnight Man, McGregor has undertaken the job of closing down an illegal after-hours enterprise at a fashionable Upper East Side nightclub. The case begins as a simple one — the club’s neighbors don’t like the idea of drunks carousing in the wee hours — but it soon turns complicated: The after-hours operation is being run by a major New York mob figure named Frank Dinelli, whom McGregor would love to put in the slammer.

When the late-night doorman, whom McGregor has bribed and who was instrumental in a successful raid on the club, is shot to death practically in McGregor’s presence (he arrives just in time to grapple with the killer), the case becomes personal.

Working with his pal, Detective Lieutenant Kevin Cohen, he follows leads that take him to the studio of millionaire photographer George Preston, to the offices of Park Avenue dermatologist Robert Jackson, and to a fancy loan-sharking operation that Dinelli is sponsoring.

They also take him to a second murder, this one featuring an ingenious method of execution, which McGregor solves through the same combination of deduction and guile with which he wraps up the rest of the case.

Kane has a fine ear for dialogue; there is some witty repartee here, especially between McGregor and a variety of New York cabdrivers. Of course, cops don’t really talk the way McGregor and Cohen do, but that’s a minor flaw.

As the jacket blurb says, “If high crime in high society is your cup of tea, you’ll especially relish this fast, crisp, upper-echelon saga of mayhem in Manhattan.” And from Anthony Boucher: “Kane has, as usual, a pretty sense of story-shape and a nice way with clues. There is a cleverly gimmicked murder, a lot of colorful night life, and much fun (and good food) for all.”

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

June 16th, 2010 at 9:03 pm

I don’t remember reading any of Henry Kane’s McGregor books, and that I regret, as all of the people who have read them have said good things about them.

I think it was because they came out in hardcover first, and I was almost entirely a paperback reader at the time. I have the Raven House edition of this book, but it never occurred to me to read it. Don’t know why.

June 16th, 2010 at 10:23 pm

McGregor is good, especially when you consider he was created late in the game when everyone had every right to think Kane was finished.

He proved everyone wrong, and with rare style.