Wed 14 Sep 2022

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: HOUSE OF CARDS (1968).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[6] Comments

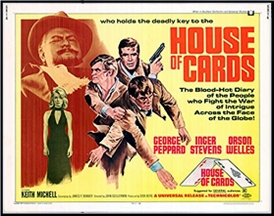

HOUSE OF CARDS. Universal Pictures, 1968. George Peppard, Inger Stevens, Orson Welles, Keith Michell, Perette Prader, Barnaby Shaw, Genvieve Cluny, Maxine Audley, William Job. Screenplay: James P. Bonner (Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr.), based on the novel by Stanley Ellin. Directed by John Guillermin.

The film opens with a the city of Paris shot from the surface of the Seine as if the viewer is floating lazily along. A man is watching from the Pont des Arts and as the POV changes we see the body he has spotted floating in the river. Soon a fisherman hooks the body and pulls it ashore, the corpse of a young well dressed man, The police are called and the man on the bridge watches as the body is recovered, a cruel smile on his lips.

The camera focuses on the man on the bridge blacking everything else out and the colorful titles suddenly fill the screen

Re-opening when they have finished on American Reno Davis (George Peppard) getting beaten badly in the ring in a prize fight and quickly tossing in the towel.

He’s an ex boxer with a chequered career who has been kicking around Europe for six years trying to write something important, but mostly just avoiding living an ordinary life or going back to the states to work on his brother’s chicken farm (“Do you know what time chickens get up?â€). He’s not lazy, just listless and without any real direction.

That changes that night as he and his friend Leo are traveling back to Paris and someone takes a shot at them.

That someone turns out to be Paul de Villemont (Barnaby Shaw) age eleven who has stolen his mother’s revolver.

Returning to the villa where Paul lives, Reno meets his over protective American mother, Anne (Inger Stevens), and somewhat cooler of head demands the boy apologize leaving on good terms.

The next day as he is planning to move on from Paris Anne shows up in a Rolls and offers him a job as Paul’s tutor and bodyguard, primarily to teach the boy how to be a boy and an American since his father, a French military hero from a distinguished military family , was killed in Algeria.

The money is good, Anne is beautiful, and Reno has nothing better to do so he agrees.

The boy very much needs to discover childhood. The household he lives in is that of an aristocratic French family run off their estates in French Algeria in the recent conflict and living in the past dreaming of past glories and injuries and something more sinister.

There is the boy’s grandmother (Patience Collier) a cold-hearted type who makes the family watch home movies of their days in Algeria every night with Paul’s creepy aunts, uncles, and cousins (Maxine Audley, Paul Bayliss, Ralph Michael), and the creepier secretary Bourdon (William Job) who was the man on the bridge. And of course there is beautiful Jeane-Marie (Perette Prader) a house-keeper who throws herself at Reno, as Anne does, both wanting something he’s not sure he wants to give.

Then there is Dr. Morillion (Keith Michell) the imperious physician who lets Reno know he is not really welcome, that Anne is off limits because she is his patient being treated for a breakdown she recently was hospitalized for explaining her paranoia about Paul being kidnapped, and that he sees to Paul as well.

At a party Reno meets Leschenhaut (Orson Welles) a friend of the family who feels him out on some distinctly fascist political opinions and the night ends with Reno decking the snide Morillion.

Still Reno isn’t fired, and continues with Paul, still thinking Anne drinks too much and is mentally unstable even claiming his predecessor was murdered, the man found drowned in the Seine. That paranoia seems more real when Bourdon and the family chauffeur try to kill him while he is fishing on the Seine with Paul then kidnap the boy and frame Reno for the murder of his friend Leo. And when he escapes the police and returns to the villa it has been closed and everyone is gone.

House of Cards is based on a novel by Stanley Ellin which came from his later period, and while critics in general tend to dismiss some of the slicker novels of this era like The Valentine Estate and The Bind, they are well written, entertaining thrillers with complex heroes who have a bit more to them than just black and white heroics. Like Reno Davis in this book and film, his protagonists are people not quite committed to ordinary life who don’t fully fit into society. They are on a high order of well written and involving suspense novels.

Hunted by the police, Reno will discover Anne had every right to be paranoid, uncover a world wide fascist conspiracy led by Leschenhaut that even reaches into the States, be pitted against fanatics determined to take over government and put the “inferior†races in their place, and arranging for Reno and Anne to die in a car wreck.

He and Anne will escape from a burning fortress, discover the secret of Paul’s honored father’s death, and he’ll join Anne in a race across France and Italy to rescue Paul from being modeled into a replacement for his father, all ending in a confrontation in the Coliseum in Rome with Leschinhaut and a brainwashed Paul with a gun, coming full circle from the opening.

Granted this is all sub-Hitichcock, and the film takes some liberties with Ellin’s novel, but I’ve always liked the film and the book, and have some fondness for Peppard’s films of this era anyway (The Executioners, The Third Day, Operation Crossbow,The Groundstar Conspiracy). I suppose it depends on your tolerance for Peppard, but mine is fairly high.

Here he is perfectly cast as the guarded somewhat footloose Reno, and Stevens brings real vulnerability to a role that makes you regret she never got to play a real Hitchcock ice blonde. Welles is Welles, but not tiresomely so and he does project menace in a minor if perverse Sidney Greenstreet key while Keith Michell manages to be equal parts superior, snide, and threatening (he and Peppard also appeared together in The Executioners).

John Guillermin captures a grittier view of Paris than say Stanley Donen’s Charade, but it is closer to the city I knew, without romanticizing the grungier areas or over relying on the usual tour of the high spots, and the film makes good use of several locations including at least one very good stunt involving leaping through a second story window to an awning below.

For some reason filmmakers always make Paris feel claustrophobic and crowded, and this one opens the city up. Unlike too many American films shot on location in Paris it isn’t half travelogue. Like actual people who live there, no one feels the need to go to the Eiffel Tower or Notre Dame or drive beneath the Arc de Triumph just because it is there.

Like Donen’s Charade and Arabesque, House of Cards it is modeled on Hitchcock with a mix of suspense, sex, sudden violence, and even some comedy. And while it lacks the star power of those two films and the genius of Hitchcock, it is handsome, diverting, has an intriguing score, beautiful cinematography, and attractive leads, with a plot perhaps more relevant today with the rise of extremism in Europe and elsewhere.

It entertains and won’t insult your intelligence, and those are fairly high bars for any suspense film.

September 15th, 2022 at 1:05 am

Nicely balanced, even-handed review.

Any material by Stanley Ellin is worth a look. He had a supple, poised manner of telling a story. When that guy’s pistons were firing, look out. Deft as hell.

Peppard: blazed like a comet over Hollywood when he arrived. Fine figure of a man. Affable and swaggering. Briefly, he had it all. ‘The Blue Max’ –sublime. Something happened, I donno what. How did he gain so much weight in such a hurry? After he lost his slim waist …well …

September 15th, 2022 at 4:07 am

Barnaby Shaw is referred to as Barnaby Ross at one point.

September 15th, 2022 at 9:00 am

As the editor of this review I didn’t catch that. Thanks, Jonathan! Barnaby Ross is a name a lot more familiar to me than Barnaby Shaw, a fellow with less than a dozen movie credits on IMDb. No matter. He deserves to be referred to correctly, and apologies to him for missing that. (And course I’ve corrected the error!)

September 15th, 2022 at 9:11 pm

Early on Ellin wrote some outstanding novels in the genre that showed many mainstream novelistic strengths and of course remained a gifted short story writer, but his later books tended to be lighter in tone and more geared toward entertainment

They succeeded at that last fully with plots that often seemed aimed at Hollywood even when they weren’t actually filmed. I always felt too many critics failed to appreciate them on their own merits.

You can’t compare them to his best books like THE KEY TO NICHOLAS STREET or THE EIGHTH CIRCLE but like Graham Greene’s entertainments they have delights of their own and Barzun and Taylor noted that in their CATALOGUE OF CRIME in the entries on Ellin though still comparing him to his more serious work.

September 15th, 2022 at 9:46 pm

I have a whole stack of Ellin books (well scattered) that I have yet to read, including this one. I hope to get to one or two of them soon, including this one. There’s just too many books, and so little …

September 16th, 2022 at 12:04 pm

I’m a fan of George Peppard and Stanley Ellin! I may have read HOUSE OF CARDS decades ago, but after reading David’s wonderful review, I’ll have to dig it out and read it again.