Tue 7 Feb 2023

Reviewed by Tony Baer: JOHN L. SPIVAK – Hard Times on a Southern Chain Gang [+] ROBERT ELLIOTT BURNS -Â I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

JOHN L. SPIVAK – Hard Times on a Southern Chain Gang. University of South Carolina Press, trade paperback, 2012. Originally published as the novel Georgia Nigger (1932).

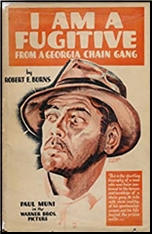

ROBERT ELLIOTT BURNS – I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang. Vanguard Press, hardcover, 1932. University of Georgia Press, trade paperback, 1997. First serialized in True Detective Mysteries magazine, beginning January 1931. Filmed in 1932, starring Paul Muni.

Hard Times on a Southern Chain Gang is a crappy title for a pretty amazing piece of work. The original title is more powerful but no longer publishable.

Spivak used some connections to get access to Georgia chain gangs in the 30’s for a supposed academic study. Instead, he took the stories he heard from the inmates and the terrible things he saw to create a novel. An amalgam character, David Jackson, is put through the veritable wringer and becomes the camera’s eye of the action.

The take home message is that life for Black folks in the South was worse after slavery than before. During slavery, a slave would cost the slaveholder serious coin. David’s grandfather cost $1800. This meant that, like a cow or a horse or other farm chattel, the farmer had a financial interest in keeping his slaves alive and relatively healthy.

But now slave labor was much cheaper. Here’s the recipe: If you need a slave, ask the sheriff to arrest some Black folks for vagrancy. Any Black man walking down the street is fair game.

Once arrested, you have a choice. Three months on the chain gang or a $10 fine. You don’t have $10, but a farmer comes by and says: “Hey, tell you what I’ll do. If you’ll come work for me, I’ll pay the fine out of your next months wages. I pay $20 a month.

You figure anything’s better than a chain gang, so you take the deal. What you don’t know is that you’ll never pay off the $10 to the farmer. The farmer will charge you for room and board, and charge usurious interest, and each month you work there you’ll be further and further in debt.

Plus unlike a slave that cost the farmer big money, you only set him back $5. So if you get sick, he’ll let you die. He’ll work you til you die, and if you refuse to work, he’ll whip you til your body’s welted and bloody.

And if you run away, the Sheriff will track you down and charge you with theft of the debt you owe the farmer, plus resisting arrest, disturbing the peace. That’ll get you a year on the chain gang or $25 dollars. And so on. You’ll never get free.

It’s a terrible story, striking, descriptive, horrific and well-told. But no one read it because that same year a white northern journalist named Robert Burns put out his autobiographical tale of his time on a Georgia Chain gang. He had a pretty bad time too. But his writing is not very descriptive. And aside from him telling you how bad it was, you can’t really visualize it because he doesn’t give you the gory details.

Burns’s tale was immediately optioned by Hollywood and made into a popular melodrama, insuring its vague memory in the public mind while the much better book by Spivak has been mostly forgotten.

But if you’re really interested in this tale of woe, of Georgia chain gangs and their lacerated legacy, skip Burns and go straight to Spivak.

I watched the first ten minutes of the Hollywoodified Burns tale and had to turn it off. If Burns was tepid — this was wretched.

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang can be viewed at:

https://archive.org/details/1932iamafugitivefromachaingangsoyunfugitivomervynleroyvose

It was later made as a film starring Val Kilmer: The Man who Broke 1,000 Chains (1997):

February 8th, 2023 at 4:50 pm

Another horrid story in the Spivak book involved a Black farmer that owned his own farm. The white farmer next door started farming on the Black farmer’s land. The Black farmer went to a (white) lawyer in town to assert his rights. The lawyer said the title was cloudy so there’s not much he can do, and changed him $150 for legal fees, putting a lien on his farm for that amount. The lawyer then sold the lien to the white farmer who then foreclosed on the farm, taking it over.

February 9th, 2023 at 12:11 am

Horrid? That’s an understatement, if ever there was one.

February 9th, 2023 at 6:58 pm

The outrage these books and the film raised among the public acted fairly quickly stirring reform. Too little and too late, but at least the public began to understand the injustice.

The most recent variation was judges paid to send innocents to private prisons so the corporate owners could make more state money.