Tue 8 Aug 2023

Reviewed by Tony Baer: LEN ZINBERG- Walk Hard — Talk Loud.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[4] Comments

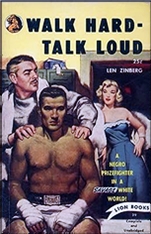

LEN ZINBERG– Walk Hard — Talk Loud. Bobbs Merrill, hardcover, 1940. Lion #29, paperback, 1950.

Before he was Ed Lacy, Len Zinberg was Len Zinberg. But he was still writing hardboiled stuff — it just wasn’t marketed as genre paperback fiction. Yet.

This one’s his first novel. And it’s a good first novel. You can kind of tell he’s not exactly sure what he wants to be yet. But he’s got a vision of justice (or a sense of injustice, anyway (which is, to me, better), and he excels at action scenes, especially those involving boxing.

The book follows Andy, a 19 year old Black kid from Harlem. It starts out and he’s scraping for a living with a shoe shine stand. He gets in a rumble with a white kid protecting his shoe shine territory. Andy knocks him out with a short left hook. Looking on, as luck would have it, is a boxing agent.

The agent brings Andy into the gym for a tryout, which he slays, and he signs him to a contract.

Andy’s excited to finally learn a trade. He figures a trade is the one thing that can keep Jim Crow off his back. He’s sick of being judged by the color of his skin. Boxing seems like the real thing. Like Joe Louis. If you’re a great boxer, you can’t be denied. It doesn’t matter your color. Greatness rises to the top.

Plus, once he becomes champ, and makes a bunch of dough, he’ll move away to some country, maybe an island in the Caribbean, where he can escape the racial curses of America and finally be treated like a man.

Unfortunately, Andy finds out the hard way that Jim Crow had infested the boxing world too. After losing a fight he’d clearly won to a local white hope, he gets invited to a party by a fellow boxer. The party is being thrown by a NY mob boss, a guy who holds the boxing world in the palm of his hand.

Seeing Andy at the party, the mob boss screams: “I don’t want any niggers at my–” And Andy hit him, a hard right under the chin, and as [the mobster] fell, a fast left cut his nose. There was a terrible stillness in the room and Andy heard his own voice quietly saying, “I don’t like people calling me that.” [The mobster] was sitting up, blood rushing out of his nose and on his expensive shirt. He cursed and jumped to his feet and he had a small black short-barreled automatic in his hand. Andy caught the hand with his right and swung with his left and [the mobster] was knocked against the wall, the gun falling to the floor. Andy kept punching him about the face and “smashed deep into [his] soft stomach — the air whistling out of his bloody mouth, his hands around his belly.”

While it was fun while it lasted, beating up a mob boss isn’t too good for the health of a boxer’s body or career. His boxing career was done. But what was left was the biggest fight of them all: against Jim Crow himself.

—-

It was alright. The best parts for sure were the boxing parts. But there were also some jolting screeds decrying anti-miscegenation (a subject Zinberg knew biblically) and scenes of Django Unchained sized wish fulfillment involving racists and their instant karmic chickens come home to roost.

There wasn’t a lot of didactic lecturing. But there was some, in the form of dialogue with Andy’s love interest, a card carrying communist. Fortunately, she tells Andy that each person has to figure things out for themselves that you can’t lecture somebody into an ideology. A point of view with which this reader gratefully agrees. Nothing bores me like didacticism.

And boredom, says Kierkegaard, is the root of all evil. Now I’m not saying Kierkegaard is right, mind you. Still, I won’t tempt Satan by belaboring the point any further.

August 9th, 2023 at 5:05 am

I sometimes suspect that Zinberg/Lacy may have been a major talent, right up there with Hammett & Chandler in the Hard-Boiled school. I’m not saying he was, but one could argue it convincingly.

August 9th, 2023 at 11:48 am

For a long profile on Ed Lacy by Ed Lynskey, along with an annotated bibliography of all his crime fiction, go here:

https://mysteryfile.com/Lacy/Profile.html

August 11th, 2023 at 7:34 pm

If not Chandler, Hammett, and Cain I put Lacy at least in the class of Whitfield, Nebel, and Burnett, far above the paperback original jungle most of his books had to rise above. Even in a more playful mode, as some of his lesser books are, his storytelling skills and the ease with which he involves you with his characters and plots in a compelling way.

He wasn’t the only voice in the genre taking on the racial issue, but he was perhaps the most consistent at it other than Chester Himes or Dorothy B. Hughes.

July 31st, 2025 at 1:09 pm

Zinberg deserved à long study. I have tried to do my best and I believe that my ED LACY, AN UNKNOWN MAN CALLED LEN ZINBERG (2023) fills many gaps. For exemple, all the articles and short-stories he wrote for African-American newspapers under his name and, as soon as 1935 under Ed Lacy alias.

A new translation of Room to Swing has been published here in France, followed by La Mort du torero (Moment of Untruth) which was not translated. At the beguining of 2027, Hold With the Hares will be published.

Of course, the work of Ed Lynskey was great!

Best regards,

Roger Martin