Sun 4 Mar 2007

Review: DAVID HUME – Requiem for Rogues

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[5] Comments

DAVID HUME – Requiem for Rogues

Collins, UK, hc, 1942. Reprints: 1946?, 1952. Collins White Circle #380, Canada, pb, 1949.

The author, first of all, is NOT David Hume (April 26, 1711 – August 25, 1776), who was a Scottish philosopher, economist, and historian, and according to at least one source, one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Nor is it his real name, for which see below. One does idly wonder why Mr. Turner chose it as a working by-line, though. It also makes it difficult to come up with information about him on Google, most of the searches picking up the wrong man, obviously.

On one website, I did come across the following, however:

From Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, which of course I turned to next, if not first, comes the following list of titles by Mr. Hume. These are the British editions only:

* Bullets Bite Deep (n.) Putnam 1932 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Crime Unlimited (n.) Collins 1933 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Murders Form Fours (n.) Putnam 1933 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Below the Belt (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* They Called Him Death (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Too Dangerous to Live (n.) Collins 1934 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Call in the Yard (co) Collins 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson; England]

• Call in the Yard • na The Thriller Mar 2 1935

• The Murder Trap • na The Thriller Apr 13 1935

• The Secret of the Strong Room • na The Thriller Dec 1 1934

* Dangerous Mr. Dell (n.) Collins 1935 [Mick Cardby; England]

* The Gaol Gates Are Open (n.) Collins 1935 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Bring ’Em Back Dead! (n.) Collins 1936 [Mick Cardby; France]

* The Crime Combine (co) Collins 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson; England]

• The Crime Combine • na The Thriller May 2 1936

• Midnight’s Last Bow • na [unknown]

• The Murder Rap • na The Thriller Jul 25 1936

* Meet the Dragon (n.) Collins 1936 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Cemetery First Stop! (n.) Collins 1937 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Halfway to Horror (n.) Collins 1937 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Corpses Never Argue (n.) Collins 1938 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Good-Bye to Life (n.) Collins 1938 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Death Before Honour (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Heads You Live (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Make Way for the Mourners (n.) Collins 1939 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Eternity, Here I Come! (n.) Collins 1940 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Five Aces (n.) Collins 1940 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Invitation to the Grave (n.) Collins 1940 [England]

* You’ll Catch Your Death (n.) Collins 1940 [Tony Carter; England]

* The Return of Mick Cardby (n.) Collins 1941 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Stand Up and Fight (n.) Collins 1941 [England]

* Destiny Is My Name (n.) Collins 1942 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Never Say Live! (n.) Collins 1942 [Tony Carter; England]

* Requiem for Rogues (n.) Collins 1942 [Tony Carter; England]

* Dishonour Among Thieves (n.) Collins 1943 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Get Out the Cuffs (n.) Collins 1943 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Mick Cardby Works Overtime (n.) Collins 1944 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Toast to a Corpse (n.) Collins 1944 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Come Back for the Body (n.) Collins 1945 [Mick Cardby; England]

* They Never Came Back (n.) Collins 1945 [Mick Cardby; England]

* Heading for a Wreath (n.) Collins 1946 [Mick Cardby; England]

TURNER, J(ohn) V(ictor)

* Death Must Have Laughed (n.) London: Putnam 1932 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Who Spoke Last? (n.) London: Putnam 1932 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Amos Petrie’s Puzzle (n.) Bles 1933 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Murder-Nine and Out (n.) Bles 1934 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Death Joins the Party (n.) Bles 1935 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Homicide Haven (n.) Collins 1935 [Amos Petrie; England]

* Below the Clock (n.) Collins 1936 [Amos Petrie; London]

BRADY, NICHOLAS

* The House of Strange Guests (n.) Bles 1932 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; London]

* The Fair Murder (n.) Bles 1933 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; England]

* Week-End Murder (n.) Bles 1933 [England]

* Ebenezer Investigates (n.) Bles 1934 [Rev. Ebenezer Buckle; England]

* Coupons for Death (n.) Hale 1944 [England]

I don’t know about you but these are all new names to me, both that of the author (and his pen names) and his characters. Back to Google, it seems. Here’s a snippet of a review from The Bookman, 1933, of the US Holt edition of Nicolas Brady’s The House of Strange Guests:

Another snippet of a review, this one from The Librarian and Book World, date?, of Brady’s The Fair Murder:

Seeing a few shorter works of fiction collected under David Hume’s byline, I checked out the online Fictionmags Index, with the following results. [* = included in CFIV list above, either as a novel serialized earlier in magazine form, or as a story collected later in book form]

* The Secret of the Strong Room (na) The Thriller Dec 1 1934 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* Call in the Yard (na) The Thriller Mar 2 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* The Murder Trap (na) The Thriller Apr 13 1935 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

A Basin of Trouble (ss) The Thriller Jun 29 1935

The Crook’s Day Off (ss) The Thriller Aug 31 1935

He Was Pinched for Nothing (ss) The Thriller Oct 19 1935

* Meet the Dragon (sl) Detective Weekly Jan 4, Jan 11, Jan 18, Jan 25, Feb 1, Feb 8, Feb 15, Feb 22, Feb 29, Mar 7 1936 [Mick Cardby]

Anything to Say (ss) The Thriller Feb 15 1936

The Wrong Bottle (ss) The Thriller Mar 7 1936

Times Were Bad (ss) The Thriller Mar 28 1936

* The Crime Combine (na) The Thriller May 2 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

* The Murder Rap (na) The Thriller Jul 25 1936 [Det. Insp. Sanderson]

Who is Midnight? (na) The Thriller Sep 5 1936

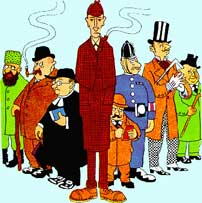

More googling, this time on Hume’s detective Mick Cardy. At this point I still knew nothing about him. On a website devoted to Inspector Maigret I discovered the following piece of art:

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

Maigret is the second gentleman on the left. Although they don’t have the original art, this cartoon came from the Storm-P museum in Copenhagen, and the curator, Jens Bing, identifies it as first appearing on the cover of the Danish pulp crime magazine Stjernehæftet in 1946. Bing sent a a copy to the Danish branch of the Sherlock Holmes Society, and here are the results they came up with for the others in the scene:

2. Maigret

3. G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown

4. Sherlock Holmes

5. Agatha Christie’s Poirot

6. David Hume’s Inspector Cardby

7. Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin

8. H.C. Bailey’s Reggie Fortune (?)

I don’t think I would gotten many of those, assuming that these are the right answers. How would you have done? But no matter, it would seem that Mick Cardby was actually Inspector Cardby, but this is not so, as we shall see in a minute. I didn’t include them in the CFIV listings, but two of Hume’s books were indicated as being the sources of films based upon them. So off I went to www.imdb.com, where I found the following useful information:

Plot summary for The Patient Vanishes (1941) aka They Called Him Death [The latter being the title of a 1934 book by Hume.]

Aha. Mick Cardby is a PI, not a gent from the Yard at all. We’ve learned something. (And you who knew already can stop the knowing looks at each other.) One more movie from the IMDB:

Too Dangerous to Live (1939) aka Crime Unlimited. [The latter being the David Hume title from 1933.] With Edward Lexy as Inspector Cardby, but no Mick Cardy listed in the credits, and no synopsis of the story.

But from the All Movie Guide comes the following Plot Description:

And from BFI, apparently there is a PI involved, after all:

I am sure that if you were to find a copy to watch, all of this confusion may be very easily straightened out. But a question remains: Who was the more important of the two characters, Inspector Cardby or his son Mick? Should both of them be included in CFIV as significant Series Characters?

And as you can easily see, Hume under his many aliases was extremely prolific. I’m sure you thought the same thing when you read through that list of mysteries up above. Could anyone who wrote so many detective novels so quickly be any good at it? Hold that thought. We’ll get back to it in a minute.

Hume also died young, at only 45. Could war injuries have had anything to do with his death? Having no answers, only these questions and more, unless you can enlighten me, I’ll move on to the major business at hand, which is a review of Requiem for Rogues.

In which the leading character in is neither Cardy, father or son, but rather Tony Carter, a wisecracking crime reporter who appeared in three of Hume’s adventures, of which this is the third. He’s rather full of himself as well, as one might put it. Here’s a piece of a conversation that takes place on page 22 between Carter and his immediate superior at the Echo:

“To commence,” announced Cartwright, your methods are so unconventional that one day you will land this paper into most serious trouble. So far the luck has been with you. That cannot last for much longer. Then you’ll be in jail, and the

Echo will be faced with a heavy libel action. In the future follow a more conservative line of conduct, be more orthodox. See?”“Surely. You don’t want any more exclusive stories. The paper really wants the official news handed out in the Press room at the Yard – and nothing else. If that is so you’re wasting your money, and my time. Get a fourteen-year-old office boy, pay him ten shillings a week, let make the Yard call three or four times a day. And he’ll be a howling success.”

Cartwright wriggled. This interview was not what he had anticipated – not by a long, long way.

Suffice it say that Carter convinces Cartwright to give him a free hand in this case of the drive-by killing of one Percival East, dead by means of a bullet between the eyes on page eight, and right before the eyes of a later berated Detective Spriggs.

By page 69, the police are confused enough – and well they should be – to give Carter a free hand as well, as the case is seemingly awash with far too many clues and then again, far too few. But the more Carter digs into the case, the more deeply Percival East is discovered to have roots in the world of crime: the rackets, blackmail, the works.

Incidentally, totally relevant to nothing, I don’t know why everyone in this book refers to members of the police force as “splits.” It’s a new one on me, but the rest of the slang I managed to decipher with no particular difficulty. Conversations, though, which should have taken a page at the most to start and end invariably took four or five, which means that Hume was either a master of dialogue or he needed these long dialogues to fill the novel to a proper length. As for myself, I will not say padding, as I found these conversations to be rather imaginative, at the least.

There is no detection in this mystery novel, per se. Carter runs around London a lot, meets with his crew of regular informers a lot, and in so doing irritates the killer a lot, and enough so to make him (or her) make moves and counterattacks he (or she) really shouldn’t have done. If Carter had only been left alone, one might think, the case would never have been solved. One might very easily be right.

This probably also answers the question I asked up above but didn’t answer until now.

March 6th, 2007 at 4:09 pm

[…] Following my review of Requiem for Rogues and my overview of author David Hume’s career, I received enough follow-up comments to warrant making an entire blog entry out of them. First from the Yahoo Golden Age of Detection group, here’s a reply from Curt Evans. Steve, […]

April 30th, 2009 at 9:57 am

[…] has come up for discussion several times on this blog, the first being this review I wrote of Requiem for Rogues. This post also contains a complete bibliography for Mr. Turner, […]

December 18th, 2010 at 3:44 pm

Happy Days !

I am in my 70’s. As a boy in the 1940’s I used my dad’s ticket in the local circulating library and read little but Mick Cardby (ok a bit of Norman Conquest as well).

They don’t write ’em like that any more (well perhaps they do, Rankin perhaps, Reginald Hill ?)

Am I getting old?

March 4th, 2013 at 3:39 pm

Thanks for the info on Hume. As you rightly point out, he’s a hard chap to run to ground.

April 16th, 2014 at 12:23 pm

I have just started to read “Requiem For Rogues” today, I came across this book many years ago in my library, however I just thought that I would start reading it now. I have a huge collection of books mainly in hardback dating from the 1920s 30s 40s 50s 60s 70s 80s which I inherited from my late father who was an avid reader. This particular hardback was in it’s third publication from 1946. very interesting.

So far this book seems