Tue 16 Sep 2025

Back to the Wells, Part 3: The Invisible Man by Matthew R. Bradley

Posted by Steve under Reviews , SF & Fantasy films[7] Comments

The Invisible Man

by Matthew R. Bradley

Alone among those oft-cited Berkley Highland editions, the cover artist for H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man (1897) is unidentified; the remainder—except the aforementioned The Time Machine (1895)—were all the work of Paul Lehr. I never owned that, because back in the old grade-school book-fair days I bought a long-gone, oversized, unidentified trade paperback, and now have a 1984 Signet edition coincidentally containing both novels.

In his introduction, John Calvin Batchelor notes that they “were written while Wells still felt the anxiety of his early life of grubbing and false starts, and represent excellent examples of a man still very shaky about this new venture, fiction writing. Both were written in a fever by a man fleeing his past and intimidated by his future,” one of unforeseen success.

Wells’s third novel was his first using a third-person narrative:

Bringing the mustard for his lunch, Mrs. Hall is surprised to see him covering the lower part of his face with a serviette, and white bandages hiding his forehead and ears, with only his bright, “pink, peaked nose” exposed.

Later replacing the serviette with a silk muffler, he refuses to be drawn out on the subject of bandaged injuries, disappointed that his luggage cannot be picked up that day from the Bramblehurst railway station. Later caught unawares before he can raise the muffler, he appears to have “an enormous mouth…that swallowed the whole of the lower portion of his face.” Describing himself as “an experimental investigator [whose] baggage contains apparatus and appliances,” he seeks solitude and has suffered an accident necessitating “a certain retirement,” sometimes shutting himself up in the dark because his eyes are “weak and painful…[while] the slightest disturbance…is a source of excruciating annoyance…”

His boxes, cases, crates, and trunks contain books, test tubes, a balance, and every type of glass bottles, packed in straw, with which the stranger is soon locked away for his “really very urgent and necessary investigations,” speaking cryptically to himself, smoothing any irregularities away with “bills settled punctual.” Speculation is rampant among the “quiet Sussex villagers”—who dub him the “Bogey Man”—especially after medico Cuss reports that the stranger, while lamenting the accidental burning of a five-ingredient prescription, displayed a seemingly empty sleeve, nonetheless held up and open. He tells Bunting, the vicar, “Something [invisible]—exactly like a finger and thumb it felt—nipped my nose.”

In June, funds exhausted, the stranger burglarizes the vicarage, unseen but heard sneezing there and at the inn, where his scattered garments and animated furniture baffle the Halls. Later, confronted by Mrs. Hall over his bill, he unveils—at last referred to by the title—and eludes Constable Bobby Jaffers’s attempt to execute a warrant; he then enlists the aid of tramp Thomas Marvel, “an out-cast like myself…. Help me—and I will do great things for you. An invisible man is a man of power.” He covers Marvel’s exit from Iping, with a bundle of clothes stolen from Bunting and Cuss and the diaries they sought to decipher, but refuses to accept Marvel’s “resignation” while forcing him to travel to Port Burdock.

Spiriting money from tills, he puts it in the pockets of Marvel, who finally takes refuge in the Jolly Cricketers; wounded in a scuffle there, the Invisible Man visits old acquaintance Dr. Kemp, identifying himself as Griffin of University College. Before telling his story, he demands to eat and sleep while Kemp peruses the papers and concludes, “it reads like rage growing to mania! The things he may do!,” writing a note to Colonel Adye. Griffin reveals finding “a general principle of pigments and refraction,—a formula, a geometrical expression involving four dimensions….to lower the refractive index of a substance…to that of air,” betrayed by blood, which “[g]ets visible as it coagulates,” or undigested food.

Playing for time while awaiting the police, Kemp hears Griffin relate experimenting on a cat in London, financed by funds stolen from his father; firing his lodging-house to cover his tracks; realizing that snow, rain, fog, or dirt can give him away; stealing his garb from a Drury Lane costume shop; and hiding out in Iping, seeking a way to reverse the process at will, for which he needs his diaries.

He wants Kemp as a confederate, and has murder on his mind. “Not wanton killing, but a judicious slaying…. [The] invisible man…must now establish a reign of terror…. And all who disobey his orders he must kill, and kill all who would defend them,” yet he is interrupted by police chief Adye, and flees the house.

Amid a carefully planned (invisible) manhunt, he smashes the head of Wicksteed with an iron rod, then writes to threaten that Kemp’s execution will mark “day one of year one of the new…Epoch of…Invisible Man the First.” Adye and the Invisible Man are injured in the siege of Kemp’s house; as he makes a break for town, the locals surround and beat his pursuer, who becomes visible after death. “First came the little white nerves, a hazy grey sketch of a limb, then the glassy bones and intricate arteries, then the flesh and skin, first a faint fogginess, and then growing rapidly dense and opaque. Presently they could see his crushed chest…his shoulders, and the dim outline of his drawn and battered features.”

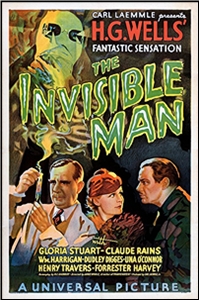

Perhaps the only true stylist of Universal’s Golden Age (1930s-’40s) horror films, James Whale (1889-1957) directed Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—which along with The Invisible Man (1933) established two of their franchises—and The Old Dark House (1932). Reunited on Frankenstein, Whale and rising star Colin Clive had been brought to New York to film Journey’s End (1930), re-creating their 1929 stage success by R.C. Sherriff on London’s West End. Whale, who had also directed the Broadway production, recruited Sherriff to adapt The Invisible Man; he considered Clive for the lead, but ultimately cast relative unknown Claude Rains when Karloff bowed out.

With cinematic scoring then still in its infancy, revolutionized that year by Max Steiner in King Kong (1933), music was rare in these films, notably an excerpt from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (1877) played over the opening credits for Dracula (1931). However, Heinz Roemheld’s uncredited score for The Invisible Man, heard sparingly at the beginning and end of the film, would be widely recycled and ultimately ubiquitous in Universal’s Buster Crabbe serials Flash Gordon (1936) and Buck Rogers (1939). Sherriff gives Griffin and Kemp (William Harrigan) first names, respectively Jack and Arthur, and opens faithfully (Wells had script approval) with Griffin’s arrival in Iping at what is now the Lion’s Head.

Clearly, Whale shared what Batchelor called Wells’s “heartfelt affection for the English yeoman class and its nosy ways, with a list of colorful village types who hover around the [inn] spying on the stranger….[i]n their eccentric and most unsinister way…”

Indelible as Jenny Hall is Una O’Connor, so memorably reunited with Whale as terrified servant Minnie in Bride, and later the beloved nursemaid Bess in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Joining her is a “who’s who” of other venerable character actors, e.g., Forrester Harvey as her innkeeper husband Herbert; Holmes Herbert as the Chief of Police; Bride’s Burgomaster, E.E. Clive, as Constable Jaffers; and Dudley Digges as the Chief Detective.

According to Paul M. Jensen’s The Men Who Made the Monsters, the film was the result of an almost two-year process incorporating “at least nine treatments and eleven scripts, prepared by twelve different writers,” e.g., John Huston, Preston Sturges, and Universal mainstays Garrett Fort—also uncredited on Paramount’s Wells-based Island of Lost Souls (1932)—and John L. Balderston. Envisioned as a Karloff vehicle, the project had another round-robin of potential directors attached, including Robert Florey, supplanted by Whale on Frankenstein. The studio also purchased the rights to, and considered using elements from, The Murderer Invisible (1931), a novel by fellow Lost Souls alumnus Philip Wylie.

Sherriff added a love interest in fiancée Flora (Gloria Stuart), whose father, Dr. Cranley (Henry Travers), employed Griffin and Kemp, the latter—here a romantic rival—saying, “He meddled in things men should leave alone,” after Griffin disappeared to pursue his experiments in private. John P. Fulton’s effects remain impressive almost a century later, particularly when Rains gradually disrobes; he and a special set were covered with black velvet, so that only the clothing registered, later combined with other footage. He earned Oscar nominations for three sequels, later winning for Wonder Man (1945) and The Ten Commandments (1956), but the Best Special Effects category was not created until 1939.

A list of chemicals found in Griffin’s old lab includes monocane, “a terrible drug…made from a flower…grown in India. It draws color from everything it touches” and, perhaps unknown to him, drove a canine test subject “raving mad.”

Griffin explains his “reign of terror” to unwilling partner Kemp (“a few murders here and there, murders of great men, murders of little men, just to show we make no distinction”) and wrecks a train, knocking out the signalman and killing 100 people. Marvel is eliminated, his function of helping to retrieve the notebooks from the inn being delegated to the unflatteringly portrayed Kemp; Whale, unlike Wells, later allows Griffin to follow through on his threatened “execution.”

Flora persuades Cranley, summoned by Kemp, that she can reason with Griffin, who says that as “a poor, struggling chemist,” he sought wealth and fame for her, then lapses into a rant about “power to rule, to make the world grovel at my feet,” scoffing that Cranley has “the brain of…a maggot…” Dismissing her warning about monocane, he slips through a police cordon and memorably skips away in stolen pants, singing, “Here we go gathering nuts in May…”

Uncredited players include Dwight Frye, John Carradine (both of whom offer the police suggestions, and later appeared in Bride), and Walter Brennan as the man whose bicycle Griffin steals; Harry Stubbs is skeptical Inspector Bird, casually murdered.

Easily penetrating an elaborate dragnet, Griffin avenges his betrayal just at the appointed hour, laughingly maniacally as he sends the trussed and screaming Kemp over a cliff in his car to a fiery death. Undone when a farmer reports, “There’s breathing in my barn,” he is burned out, forced into a snowstorm that makes his footprints visible, and shot, his dying words to Flora echoing Kemp’s aphorism. His star-making performance more impressive without the use of the facial features seen only in death, Rains excelled as Prince John in Robin Hood and Captain Renault in Casablanca (1942), the latter and Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946) earning him two of his four Best Supporting Actor Oscar nominations.

Universal belatedly followed the film with an erratic “series” stretching the definition of a sequel, including not one but two encounters with their other resident cash cows, first with a cameo (non-)appearance by Vincent Price at the end of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), and then the inevitable …Meet the Invisible Man (1951). Price had starred in The Invisible Man Returns (1940), clearing himself of a murder charge with the serum from Jack’s brother, Frank (John Sutton). That same year, eccentric inventor John Barrymore turned Virginia Bruce into The Invisible Woman with an invisibility device in a screwball comedy featuring Charlie Ruggles, Margaret Hamilton, and Shemp Howard.

As with Sherlock Holmes, Universal drafted the character for the war effort with Invisible Agent (1942), pitting Jack’s grandson, Frank (Jon Hall), against Axis spies Peter Lorre, in his Japanese Mr. Moto-mode, and Sir Cedric Hardwicke, the culprit in Returns. And, just to maximize the confusion, Hall, uhm, returned in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944) as apparently unrelated Robert Griffin, the escaped psycho whose crime spree is enabled by mad scientist John Carradine. But perhaps the true revenge is his immortality in various media, including a nominal 2020 remake, innumerable rip-offs, multiple eponymous TV series, Rankin-Bass’s Mad Monster Party? (1967), comic books, and on radio and stage.

Up next: The War of the Worlds

Edition cited/works consulted:

Batchelor, John Calvin, introduction to The Time Machine and The Invisible Man (New York: Signet Classic, 1984), pp. v-xxiii.

Baxter, John, Science Fiction in the Cinema: 1895-1970 (The International Film Guide Series; New York: A.S. Barnes, 1970).

Brosnan, John, Future Tense: The Cinema of Science Fiction (New York: St. Martin’s, 1978).

Brunas, Michael, John Brunas, and Tom Weaver, Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990).

Gunn, James, editor, The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (New York: Viking, 1988).

Hardy, Phil, editor, The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Science Fiction (Woodstock, NY:Overlook, 1995).

Internet Movie Database (IMDb)

Jensen, Paul M., The Men Who Made the Monsters (New York: Twayne, 1996).

Kinnard, Roy, Tony Crnkovich, and R.J. Vitone, The Flash Gordon Serials, 1936-1940: A Heavily Illustrated Guide (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008).

Wells, H.G., The Invisible Man, in The Time Machine and The Invisible Man, pp. 105-278.

Wikipedia

Online source:

https://archive.org/details/the-invisible-man-1933_202105.

September 17th, 2025 at 3:57 pm

THE INVISIBLE MAN is one of the great SF films of all time. In my favorite top five, maybe in the top two. Glad to read this, Matthew. Thanks!

September 17th, 2025 at 9:07 pm

Excellent overview! Wells’ classics are timeless. For me, a little of Una O’Connor’s shrieking goes a long way. Ah, the beautiful Gloria Stuart.

September 18th, 2025 at 1:01 pm

Steve: My pleasure. I think this may be the very best, or at least my favorite, Wells adaptation.

Fred: It’s a funny thing–while watching this for the umpteenth time, I thought, “By all rights, Una’s screeching should annoy the hell out of me, and yet somehow, I find myself amused and charmed.” Go figure. Whale obviously loved her!

September 18th, 2025 at 6:00 pm

The consistent theme for the inconsistent series is that the formula turns whoever uses it into a raging sociopath and monomaniac. That’s as much from Wylie’s MURDERER INVISIBLE as Wells. Whether a hero as in REVENGE and AGENT, or a villain the Invisible Man is always a shade nuts.

Even the Invisible Woman gets a bit giddy on the stuff.

September 19th, 2025 at 7:49 am

I saw in my research that much has been made of Wylie’s monomaniacal theme and its reflection in the film. I happily accept that it may be more prominent in his novel (which I’ve never read) than in Wells’s, but was careful to quote the latter to demonstrate its definite presence there as well, in both Kemp’s and Griffin’s dialogue, including the “reign of terror” phrase.

September 27th, 2025 at 3:53 am

Wylie does his usual ‘superman’ bit in THE MURDERER INVISIBLE, though I suspect as much as anything the studio acquired his novel to avoid any legal challenges that might be made. That and Wylie’s already prestigious name were natural contributions to the project.

Protecting themselves legally and attaching an American literary figure to the project probably acted as a buffer from any money men who might think twice about what was a very British film compared to the other Universal horrors.

And yes, Wylie does make more of the monomania of his villain than Wells does, though it is certainly there in Wells. Wylie’s book is a good deal more melodramatic than Wells slim volume.

November 14th, 2025 at 4:26 pm

[…] fourth in my sextet of H.G. Wells posts for Mystery*File, devoted to The War of the […]