Sun 1 Mar 2020

Mike Nevins on the Uncollected Pulp Stories of CORNELL WOOLRICH.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Pulp Fiction , Stories I'm Reading[15] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

A few weeks ago I received an email from bookseller Lynn Munroe, asking me a question about the uncollected short stories of Cornell Woolrich. The result was that I got interested in how many uncollected stories there were and how many might be worth collecting. It will take more than one column to explore these questions but let’s start here.

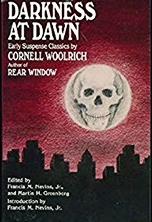

For the first two years in which Woolrich published crime-suspense stories, the number of uncollected tales is zero. Why? Because I brought together all three of the tales that first came out in 1934 and all ten of those that appeared in ‘35 in the collection DARKNESS AT DAWN (1985). Woolrich’s output grew exponentially in 1936: a total of 26 crime stories, earning him a total of $4,300, which was a respectable annual salary back then.

Some of them—for example “The Night Reveals†(Story, April 1936), “Johnny on the Spot†(Detective Fiction Weekly, May 2, 1936), “The Night I Died†(from the same magazine’s August 8 issue) and “You Pays Your Nickel†(Argosy, August 22, 1936), which is usually reprinted as “Subway‗rank among his most powerful short stories. Others from that year—including, I fear, most of the dozen that remain uncollected—are pretty terrible.

The year kicked off with one of the worst tales he ever perpetrated; perhaps the worst of his career. The mild success of the Popular Publications pulp chain with weird-menace magazines like Dime Mystery inspired rival entrepreneur Ned Pines of Thrilling Publications to launch a competing monthly called Thrilling Mystery, which debuted in October 1935 under editorial director Leo Margulies (1900-1975).

During its 50 issues the magazine offered a parade of strange cults, diabolic rituals, gruesome murders, sadistic villains, slavering beasts and (of course) beautiful young women shivering in peril. Woolrich dipped his toes into these weird waters just once. Like the 1935 classic “Dark Melody of Madness†(better known as “Papa Benjaminâ€) and the 1937 classic “Graves for the Living,†“Baal’s Daughter†(Thrilling Mystery, January 1936) is about hapless innocents falling into the clutches of repulsive religions.

But this version of the story is so sloppily and luridly written, so overloaded with stupid inconsistencies and grotesque twaddle, that to claw one’s way through its pages is an act of masochism. Narrator Bob Collins visits his psychiatrist friend Dr. Dessaw to ask for help in freeing his fiancée Gloria’s dotty aunt from a Westchester cult.

As Woolrich Coincidence would have it, the head of the cult is Dessaw, who drugs Bob and spirits him to the religion’s headquarters mansion on the banks of the Hudson, where in rapid order our hero is stripped to his shorts, flogged by a tongueless black giant, menaced by a man-eating panther, tortured with boiling oil injected into his veins, forced to kneel before a woman calling herself the reincarnated goddess Ishtar, forced to help lure Gloria to the mansion for ritual sex with with the god Baal who of course is Dr. Dessaw, and so on and on long past our endurance.

The narrative throbs with clunkers like “The fiend on the throne stood up and turned to me as I quivered there, ashen-faced†and “I was prone there, at the mercy of the he-devil and the she-devil….†How desperate must Woolrich have been to have cranked out this garbage?

Of the dozen uncollected Woolrich stories from 1936, Detective Fiction Weekly was the original home of seven, including two that might well deserve collection. Not, though, the first pair we consider here. “Blood in Your Eye†from the March 21 issue is an insanely bad cop story set in an anonymous city on which Woolrich sticks the label Los Angeles.

Mitchell, a rambunctious young homicide dick, is the only one who sees the truth when a murder victim is found in a rooming house with the image of his killer apparently imprinted on his eyes. Instead of sharing his insight, Mitchell throws down his badge in disgust at his colleagues’ willingness to believe medieval superstition and goes out to solve the crime lone-wolf style.

The hunt takes him to two venues that Woolrich was to use over and over, a manicurist’s booth and a dance hall. For this one you have to accept that neither a roomful of cops nor the medical examiner can tell the difference between genuine and glass eyes, but the climax is violent and the central gimmick Guignol-gruesome.

Just two weeks later, in the magazine’s April 4 issue, came “The Mystery of the Blue Spot,†which Woolrich submitted as “Death in Three-Quarter Time.†In a lifetime of reading whodunits I’ve never come across an alibi gimmick as wacko as this one. Homicide cop Dennis Small happens to be in the Curfew Club on the night when the specialty dancer Emilio is shot to death in his dressing room just a few minutes after he and his partner Lolita have finished performing a bizarre new number.

All the evidence points to chorus line dancer Mary Jackson, for whom Emilio was about to dump Lolita. This tale too is never likely to be reprinted or collected so I might as well give away the solution: Lolita herself killed Emilio before the dance, then rigged herself in a crazy costume and went out into the spotlight and convinced a clubful of people that she was both herself and her partner! The story becomes interesting only in the final scenes when Woolrich makes us empathize with her for two crucial noir reasons: she had lost her love and she’s about to die.

For the next uncollected story we jump into the summer months. “Nine Lives†from the June 20 number is set in the waterfront district around New York’s South Street. Demon newshawk Wheeler stumbles onto the story of an old bum who’s been treated by three sinister strangers to booze, food, clothes, and to an insurance policy on his life. The best scene finds Wheeler bound, gagged and left for dead at the bottom of an old-fashioned bathtub filling with water, but even in this serial-like incident there’s nothing terribly urgent.

Later that summer, in the August 15 issue, came “Murder on My Mind,†the earliest appearance in Woolrich and perhaps the earliest in crime fiction of a plotline which was a staple of film noir classics like SO DARK THE NIGHT (1946, directed by Joseph H. Lewis) but ultimately goes back to the Greek tragedy OEDIPUS TYRANNUS.

Marquis, the detective narrator, is assigned with his partner Beecher to the brutal murder of a harmless cigar-store clerk, but as the investigation goes forward, countless tiny details push Marquis and the reader closer and closer to becoming convinced that the murderer is Marquis himself.

This tale has never been reprinted or collected as it first appeared but a heavily revised and less crudely written version was included as “Morning After Murder†in the paperback collection BLUEBEARD’S SEVENTH WIFE (Popular Library pb #473, 1952, as by William Irish).

The trademark Woolrich combination of breathless urgency and plot flubs permeates the long story which he submitted as “Right in the Middle of New York,†but it’s so packed with action and tension that one barely notices that nothing in it makes sense, not even the published title, since no murder is committed at all in “Murder in the Middle of New York†from the September 26 issue.

Tony Shugrue, a relatively honest protégé of mobster Chuck Morgan, is set up by his mentor with phony references and gets hired by wealthy Cole Harrison as chauffeur for his beautiful and spoiled daughter Evelyn. Unaware that he’s married, Evelyn makes several passes at her driver, and for a while we’re reminded of the romance between another flighty heiress and her chauffeur in Woolrich’s 1927 pre-crime novel CHILDREN OF THE RITZ.

Finally Tony realizes that Morgan plans to kidnap Evelyn, hold her for ransom, kill her and leave him to take the fall. From this point on the story morphs into a wild roller-coaster ride crammed with thrills, anguish and suspense as Tony fights to save himself and his wife and Evelyn from the gang. Some of the dialogue creaks—“‘Rats!†he hissed viciously through his teeth. ‘Lower than rats, even!’‗and the crucial scene requires Tony literally not to recognize his wife at close quarters.

But the irresistible Woolrich urgency sweeps away all nitpicking into the ash heap and suggests that this one of the uncollected dozen may deserve being revived.

I feel the same way about “Afternoon of a Phony†from the November 14 issue—so much so that it was reprinted in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine (June 2012) at my recommendation and with a new introduction by me.

The story is something of a departure for Woolrich, a charming, clever and bizarre whodunit where the detective role is played by a con man. Clip Rogers steps off the train at the Jersey seaside resort of Wildmore and is instantly mistaken by the brainless local cops for Griswold, the supersleuth from Trenton, whom they’d sent for to help solve the bludgeon murder of a woman in one of the town’s vacation hotels.

What complicates the case beyond the local yokels’ power to unravel is that the woman’s eight-year-old son, who witnessed the crime in the middle of the night but is too young to understand its meaning, has identified as the murderer a man with a perfect alibi. Rogers exposes the real killer rather neatly, but the story becomes distinctively a Woolrich tale only afterward when, as in “The Mystery of the Blue Spot,†a criminal motivated by lost love takes center stage and, for a page or two, becomes a deeply sympathetic character. His comment that the impostor Rogers is more humane than any cop he’d ever met is evidence that when Woolrich drew genuine cops as brutal thugs he wasn’t doing it inadvertently.

His final 1936 appearance in Detective Fiction Weekly was one of his weakest, but for anyone with a little knowledge of law, it’s a coffee-out-the-nose classic. The year’s last issue, dated December 26, included “The Two Deaths of Barney Slabaugh,†in which Woolrich dusted off his favorite James M. Cain plot twist, backdated it forty years, and threw in so much of the tinny insult humor and gangster stereotypes from the current James Cagney movies that the illusion we’re in the New York of the 1890s isn’t sustained for a microsecond.

Manhattan racket boss Emerald Eddie Danberry is persuaded by his shyster lawyer Horace Lipscomb that the proper way to kill rival mobster Barney Slabaugh is to take the man prisoner, frame himself for Barney’s murder beforehand, and get himself acquitted in court. Then, Lipscomb explains—foreshadowing an infamous recent comment by Donald Trump?—even if Danberry were to murder him in full view of a thousand people he could never be prosecuted for it.

Danberry asks for the name of this marvelous rule of law. Lipscomb replies: Why, it’s the Statute of Limitations! (Cue the coffee.) Fighting DA Barry McCoy, one of the city’s few uncorrupt officials, tries to snooker the plot, and fate works another Cain trick to help him out in this super-pulpy tale, which is full of police brutality, casual racism and enough Woolrich-style wisecracks to sink an aircraft carrier.

So much for eight out of the dozen, and quite enough for one column. I’ll finish the tabulation next month. With perhaps a bonus thrown in to boot.

March 1st, 2020 at 10:57 pm

Nothing finer than Nevins on Woolrich — thanks!

March 1st, 2020 at 11:07 pm

“‘Rats!… Lower than rats, even!’â€

I’ll remember that for next time I can’t swear.

March 2nd, 2020 at 7:52 am

The plot described for “The Mystery of the Blue Spot†sounds more or less identical to Carter Dickson’s short story “Death in the Dressing-Room†from 1939, featuring Colonel March.

I have even seen the british TV version of that one starring Boris Karloff as March.

March 2nd, 2020 at 8:46 pm

Thanks, HÃ¥kan. I’ve not read either story, but I’ll try checking them out. The Carter Dickson story will be easier to find, by far.

March 2nd, 2020 at 5:54 pm

Nice to know even the masters struggle.

March 2nd, 2020 at 8:47 pm

And when he was bad, he was horrid.

March 3rd, 2020 at 12:09 am

You know, this article sounds like the introduction to a new Woolrich collection (hint, hint). Thanks for reading these so that we don’t have to 🙂

March 31st, 2020 at 4:11 pm

Mike:What do you know about “Last Night A Man Died” in Mike Shayne, Dec 1958? I could not find it in your book. Was this a resubmit of an earlier story under a different title, as he was prone to do?

March 31st, 2020 at 7:34 pm

I haven’t checked with Mike, but this is what I’ve found so far:

According to the online Crime Fiction Index, “Last Night a Man Died” was first published in I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes, Lippincott 1943, as “Last Nightâ€. (as by William Irish).

Hubin then says that “Last Night” was published earlier in Detective Story Magazine Sept 1940, as “The Red Tide.â€

Also from

http://www.otr.com/blog/?p=1216

some more background for the story, which was also produced as a radio play for Suspense.

April 1st, 2020 at 4:10 pm

[…] begin with the unfinished business from last month, in other words with the final four uncollected Cornell Woolrich stories from 1936. During that […]

April 29th, 2020 at 7:11 am

I hate to admit it, but I would buy and read a collection of The Worst of Cornell Woolrich. Like Philip K. Dick or H.P. Lovecraft, he wrote some awful stuff, but with all three of them, the awful stuff still remains distinctively and uniquely theirs.

April 29th, 2020 at 1:05 pm

And each very distinctive, each in their own way. You can’t mistake any of their work for that of anyone else’s.

May 16th, 2020 at 7:05 pm

Here is another one for Mike. What can you tell me about “The Case of the Two-Timing Blonde” published in “Fury”, May 1962? I cannot find it in your book.

December 21st, 2022 at 4:21 pm

I’ve just read ‘The Case Of The Two-Timing Blonde’ in the May 1962 issue of Fury magazine, and wonder whether it’s an original story which was published for the first time in that magazine and has never been reprinted.

June 15th, 2023 at 5:50 am

Please David, tell us what’s this story about.