Sun 14 Mar 2010

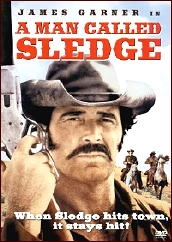

A Western Movie Review: A MAN CALLED SLEDGE (1970).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[6] Comments

A MAN CALLED SLEDGE. Columbia Pictures, 1970. James Garner, Dennis Weaver, Claude Akins, John Marley, Laura Antonelli, Wayde Preston. Producer: Dino de Laurentiis. Directors: Vic Morrow (also co-screenwriter) & Giorgio Gentili (the latter uncredited).

What were they thinking? A spaghetti western filmed in Spain starring three of the most likable guys in American TV at the time as despicable villains? No way. There’s no chance in the world that these fellows could have pulled it off, and they don’t.

From the title alone, you might think that this bit of tomfoolery was meant to be a spoof, but as the movie goes on it will gradually sink in, as if against your will, that they were deadly serious about this. Filmed in beautiful knock-your-eyes-out Technicolor, the movie itself is a shake-your-head-in-wonderment deadly bore.

All except for a few moments around the two-thirds mark, that is, when Luther Sledge and his gang manage to steal $300,000 in gold from a well-fortified prison from the inside out. The rest of the movie is filled with action, all right, but of the uninspired gratuitous kind, of which other spaghetti westerns are equally filled. Try to imagine James Garner with a truly evil glint in his eye, and you can’t.

Henry Fonda could have done this. James Garner is essentially just too nice. In Sledge, he only succeeds in looking (and acting) dumb. Why would he need the money (to be split numerous ways) when his steady girl friend Ria (Laura Antonelli) begs him not to go through with his plan? She wants him (heaven knows why), not the money.

The plan which does not turn out well in the end, as you might expect, but what you will not expect is how dull-witted (if not feeble-minded) the gents are who pull off this heist are, only to let the proceeds slip through their fingers again so easily. (Which of course is the whole point, and points, I will concede, we will accept however we obtain them.)

While the scenery and the colors are absolutely wonderful, you do have to ignore all of the fancy camera positions and shooting angles whenever the actors get on stage, as they are prone to do. All the camera shots do is call attention to themselves, and why the movie had to be redubbed back into English is beyond me.

PostScript: It is my contention that you can take any western and by watching it, but totally ignoring who the actors are, place it in the right decade, whether it be the 1920s, 30, 40s and all the way up. The themes, the settings, the clothes, the hair styles, the atmosphere — the idea of what a western was supposed to be changed decade by decade — and reflected that decade exactly.

This is neither the time nor place to develop this thesis further, but I will, someday.

March 15th, 2010 at 1:38 am

According to my notes in Garfield’s Western Film book, I saw this movie in 1998 and liked it, probably because it was different from the usual Italian western. Garfield says it’s brainless but well acted. His book deals with the “A” westerns and he is extremely critical, so much so that sometimes I wonder why did he write a book about a subject that he finds fault with over and over. I guess he was always looking for the very best westerns, so for him to say “well acted” is like a rave review.

I agree with Steve’s postscript about westerns changing each decade. My favorites being the 1920’s and 1930’s when the B-western was king. But I like many of the later westerns also and Garfield’s book is just about the best guide to the A western, though like I said, highly critical. This of course is better than not being critical at all like many books on the western, which seem to like everything.

March 15th, 2010 at 2:39 am

Walker

I should refer to Garfield’s book more often, but I find that I seldom do. It’s not that he’s overly critical. I agree with him more often than not.

For example, if he called this movie brainless, I used the words dumb, dull-witted and feeble-minded in turn.

But well acted? Compared to a Monte Hale movie, sure. The three main players, Garner, Weaver and Akins, couldn’t turn in bad performances if they tried. On the other hand, no, I don’t think they were on their A-game here, or if not that, they were having a good time and did their best but simply couldn’t overcome the handicap of the script.

There are some really spectacular scenes in this movie, though. One impressive one that came back to me after I wrote the review is the one on the open plains with Garner riding up to the platoon of soldiers guarding the wagon with the gold, as they spread out in a well-rehearsed formation lined up against him, 40 men wide.

And for some reason I liked the opening scenes that took place in the snow. Somehow you don’t often see snow in Western movies. You have to watch Sgt Preston and Alaskan gold rush movies to see weather like this.

It looked real to me, and I’ve seen enough snow for two lifetimes.

— Steve

March 15th, 2010 at 2:53 am

Garner could play a hardass — as in DUEL AT DIABLO — also with Dennis Weaver in a good dramatic role (but a bigot, not a villain), but this film is so inept, and Garner and Weaver so miscast you have to keep wondering what they were thinking.

Akins wasn’t quite as big a stretch as a villain, but by this time more likely to play the comedic variety.

Just why anyone would waste Garner’s considerable charm trying to turn him into a second rate Clint Eastwood or Lee Van Cleef is a mystery even the readers of this blog couldn’t solve.

Re Garfield, didn’t he once say they should have stopped making westerns when Gary Cooper died? In this case he may well have been right.

Garner was good in another humorless role as Wyatt Earp in John Sturges HOUR OF THE GUN, but it always seemed wasteful to cast him in a role that ignored his considerable charm on screen.

March 15th, 2010 at 6:20 am

I’ve tried to get through this a couple times, without success.

March 15th, 2010 at 2:00 pm

Sometime in 1971, Garner went on with Johnny Carson to promote his new TV series, Nichols. When Carson asked him why he was leaving Films to go back to TV, Garner proceeded to demolish his movies, claiming that he had “more bombs than Burt Reynolds”, and citing this picture, which he called “Sludge”, as the worst of the lot. Ol’ Jim drew big boffs, but Nichols didn’t take; Rockford was still a few years away.

Ah, history…

March 15th, 2010 at 2:36 pm

David:

Wasteful of Garner’s charm on the screen? Yes. That sums it up, in a nutshell.

Dan and Mike:

Believe me, it was difficult not to use the word “sludge” when commenting on this movie, but it would have been way too easy. Garner could say it, but I couldn’t. It really isn’t as bad as “sludge,” but if Garner thought it was his worst movie, I wouldn’t argue.

— Steve