Sat 13 Oct 2012

Mike Nevins on PIÈGES & CORNELL WOOLRICH (Part 2) and A. A. FAIR (Bedrooms Have Windows).

Posted by Steve under Columns , Mystery movies[2] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

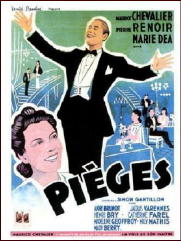

Since my last column I’ve seen Pièges, the French film from 1939 with so many strange links to Cornell Woolrich, and discovered even more of the same. I’ll limit myself here to three.

First of all, the movie is episodic in just the way so many of Woolrich’s best-known novels are episodic. It’s impossible that director Robert Siodmak and the screenwriters borrowed the structure from a Woolrich novel of that sort since all of those novels, beginning with The Bride Wore Black (1940), postdate Pièges.

Could the filmmakers have known of Woolrich’s first use of episodic structure in the long 1937 novelet “I’m Dangerous Tonight� Barely possible but most unlikely since that tale remained buried in the pulps for decades and wasn’t collected until 1981.

Secondly, for just a minute or two, beginning with Marie Dea’s discovery of her vanished girlfriend’s bracelet in Maurice Chevalier’s desk, Pièges evokes the classic Woolrich situation where the protagonist is made to seesaw back and forth between believing the person he or she loves is innocent and accepting the evidence of the other’s guilt. The earliest Woolrich story in this vein is “The Night Reveals†(1936) so the filmmakers could have known of it.

Third, when Chevalier in Pièges is put on trial for murder, director Robert Siodmak covers the scene in just a few impressionistic fragments. Woolrich in Phantom Lady (1942) covers the trial of Scott Henderson in somewhat the same way: prosecutor’s closing argument, jury verdict, death sentence. He could have chosen this approach simply because he knew no law and didn’t care to learn any, or because it was suggested to him from seeing Pièges. We’ll never know.

Pièges was released in France late in 1939, apparently just before the outbreak of World War II. Was it ever released in the U.S.? Yes it was. In the chapter on Siodmak in his 1994 book Beyond Hollywood’s Grasp: American Filmmakers Abroad, 1914-1945, Harry Waldman tells us that its original English-language title was Personal Column and quotes from the review of it that appeared in the New York Times. Clearly Woolrich could have seen the picture.

But did he? Since there’s no reason to believe he knew French, it’s unlikely he would have gone unless the print shown in New York was subtitled. Was it? Waldman doesn’t tell us and so far I haven’t found the answer elsewhere.

Siodmak is included in Beyond Hollywood’s Grasp because Harry Waldman believed he was American by birth. In fact, as I mentioned last month, the director was of German Jewish descent and his birthplace was Dresden. But the myth that he was a son of the South, born in Memphis, has circulated for generations. I must say I’m grateful that Harry Waldman accepted that myth. His mistake made my research for this month’s column ridiculously easy.

In my high school and college days I read just about all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels — except those that hadn’t been published yet! — and some but not all of the novels about Bertha Cool and Donald Lam that he wrote as A.A. Fair.

Last month I pulled out one that as far as I could remember I hadn’t read before and gave it a try. The results are mixed. Bedrooms Have Windows (1949) opens in the lobby of a large hotel to which, as we learn later, Lam has trailed a suspected con man. Suddenly a petite and gorgeous blonde, clearly meant to evoke Veronica Lake, invites Donald to escort her into the hotel’s cocktail lounge.

There she spins a yarn that takes them both to a remote motel where they register as husband and wife. The woman walks out on Lam around the same time that a man in another unit of the motel apparently kills his mistress and then himself. All this in the first couple of chapters!

Eventually we learn that the counter-plotting stems from the blonde’s determination to break up the marriage between the man her sister loves and the tramp he actually married and a blackmail ring’s determination to cash in on the situation. But, if I may mangle metaphors, under scrutiny much of the plot labyrinth collapses like a house of cards, which is an all too common fault in Gardner.

The coincidences that keep things moving might have fazed a Harry Stephen Keeler, and the storyline suffers from a number of coffee-out-the-nose elements, for example that the police accept as an obvious suicide the death of that guy in the motel who, as Gardner omits to tell us till near the end of the book, was shot between the eyes.

I wouldn’t rank this as one of the finest in the Cool and Lam series, but it moves fast and has plenty of the adversarial dialogue that was a Gardner trademark and reflects its time well, with plenty of references to the skyrocketing inflation of the years right after World War II. I don’t recommend it strongly but I can’t call it worthless either. Shall we say one thumb down?

This month’s column is both shorter and later than usual. Why? Because I have been and still am putting in a slew of hours on the index to Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection. Gad, what drudgery! The book will come out around February and a short excerpt will appear in the January 2013 EQMM. I hope those who read this column regularly will keep an eye out for both.

October 14th, 2012 at 11:47 am

As either chance or good fortune would have it, I’m reading an A. A. Fair novel right now. It’s the Hard Case Crime reprint of TOP OF THE HEAP, originally published in 1952. I’m only half way through, so I can’t say anything about how good it is except that I’m enjoying so far.

It’s easy to tell that “Fair” and Gardner are the same author, although the secret, if there ever was one, was revealed publicly very quickly anyway. A lot of people I know like the Fair books better, perhaps because of the PI setting. The Perry Mason books depend on the courtroom scenes to set off the fireworks, and thus may be less interesting to some.

But there’s more of an edge to the A. A. Fair books. (You do have to put up with Bertha Cool, who’s sharp enough, but who’s often used for comedy relief.) It’s Donald Lam who’s the brains of the outfit. He’s also good-looking enough for women to be attracted to him and start telling him their life stories, a useful trait when you’re a detective on a case. At least in the one I’m reading, anyway.

October 15th, 2012 at 10:01 am

I’m glad to see that ELLERY QUEEN THE ART OF DETECTION will soon be published. I checked amazon.com but so far they do not have it available for pre-order. This is a book that we all will be interested in.