Fri 17 May 2013

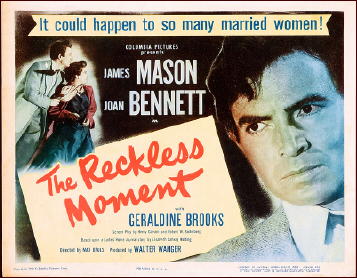

A Movie Review by Walter Albert: THE RECKLESS MOMENT (1949).

Posted by Steve under Conventions , Crime Films , Reviews[17] Comments

Movie Reviews by Walter Albert

The University of Pittsburgh recently hosted the annual meeting of the Society for Cinema Studies and more than 150 scholars spent four very busy days delivering and listening to papers, attending film showings, and socializing. There were twenty-nine panels, each of them consisting of the reading of three or four papers, followed by discussions, and there was a variety of screenings, highlighted by Robert Altman’s 1982 film, Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, which the director attended for a post-screening session at which he responded to questions from a large and very sympathetic audience,

The general topic of the convention was film genre, and the often sparsely attended screenings — film scholars seem to prefer to talk and be talked at rather than cluster anonymously in improvised screening rooms — featured a series of films “on, in, and beyond the genre.”

Since the films were scheduled at the same time as the panels, I was constantly faced with agonizing decisions. However, I was able to reconcile most of my warring interests and managed to spend several hours in the dark watching Frank Borzage’s Mannequin (1938), a “melodrama of fashion and fetishism with Joan Crawford”; Dario Argento’s stylish horror film, Suspiria (1977); Robert Altman’s very individual and probably unclassifiable comedy drama, Brewster McCloud (1970); and Max Ophuls’ 1949 movie, The Reckless Moment, in addition to the festival screening of Altman’s Jimmy Dean film.

Since I had already seen DeMille’s Unconquered (1947), Cassavetes’ Gloria (1980), and William Richert’s Winter Kills (1979), I managed a fairly comprehensive coverage of the convention films.

One of the things that was clear from several of the panels I attended was that there is increasing recognition of the fact that the sub-genres (musical, western, science-fiction, film noir) are not aIways “pure” and there is a fair amount of “bleeding” among the various types, with, for example, elements of the crime film or film noir turning up in westerns or in musicals.

Since writers on film have traditionally had difficulty defining film noir, establishing firm chronologies, and identifying those films which are undeniably noir, this makes it possible to examine a wide range of films in a number of different categories. Anyone who has looked very closely at the two major books on film noir, the Silver/Ward Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (Overlook Press, 1980) and Foster Hirsch’s work, The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir (A. S. Barnes, 1981), will have been struck by the lack of agreement on the basic body of films thought to constitute the official canon.

There is, thus, under way what could be a very fruitful re-examination of the subject , and I would expect that over the next few years there will be major reformulations that will both define more precisely noir elements and refine their applications to particular films.

While both Silver/Ward and Hirsch list Max Ophuls’ Reckless Moment in their filmographies, Silver/Ward point out the anomaly of casting a woman as the potentially doomed victim, rather than, as is usually the case in noir films, the tracked male. The casting is also ironic in that the woman is played by Joan Bennett, who was the destructive femme fatale in Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Window, here playing an upper middle-class housewife who embarks upon a sequence of lies and deceptions to protect her daughter whom she mistakenly believes to be responsible for the death of her blackmailing lover.

The film is based on a story by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, “The Blank Wall,” and has all the elements of standard woman-in-peril magazine fiction but reshaped by the superb direction of Ophuls into a subtle study of middle-class morality threatened by a seductive outsider (Shepperd Strudwick) who is “removed” and then replaced by an even more potentially dangerous threat (a blackmailer, James Mason, working with a totally unprincipled partner).

The strength of the film is not only in the fluid, accomplished camera work which tracks Bennett in her increasingly more frantic quest for salvation and liberation, but in the bond which develops between Mason and Bennett, the rootless outsider, the black sheep, as he tells her, of his family, and the mother whose only concern is to protect her daughter from the consequences of her folly and keep the stain from contaminating the house and the other members of the family.

The film is at its most intense and claustrophobic (she is, after all, walled in by her fears and assumptions) in its handling of the interior spaces of the Harper house. Bennett paces incessantly through the house, nervously chain-smoking, trying to hide her machinations from her family, as if she were turning in a cage.

In the foreground, the camera is most obsessive about Bennett’s every move, but it is also recording, in the background, the routine of the family, so that the spectator is bound by a sense of a precarious balance between the two levels and of the constant threat of the possibility of the rupturing of the fragile membrane that separates the two.

Bennett plays the role with a dark distraction in which she see ms always to be just a bit to one side of the on-screen action, plotting her next move. She is frequently interrupted, never really alone — even when she is driving with Donnelly, the character played by Mason, at a traffic light someone leans from the next car to talk to her.

She is always tracked by the camera, but this is symptomatic of a larger trajectory at which her every movement seems to coincide with an intersection. There is no one moment in the film that is in itself irretrievably reckless. It is rather the narrative, restlessly exploring the implications of movements, that is reckless.

Lucia Harper (Bennett) can only be saved by the intervention of an outside agency, initially threatening, finally converted into something benign and protective, a member of her extended family taking from her the role she cannot herself carry off successfully and restoring her as manager of the household and bearer of the telephone message to a no longer threatening exterior world, “Everything’s fine.”

There are some of the recognizable features of film noir in the depiction of the doomed character (here uncharacteristically rescued), in the menacing shadows and reflections, and in the atmospheric — and sometimes sordid — milieux that we associate with the genre. But The Reckless Moment is no more to be restricted by a characterization of genre than any other film that uses form not for constriction but for expansion and elaboration.

This is probably not a film of the same distinction as Ophuls’ Pleasure, The Earrings of Madame X, and Lola Montes, but it is a film of uncommon intelligence and taste, transforming its materials into something at once imperious and elusive, a perfect demonstration of Ophuls’ belief that, in art, “the most insignificant, the most unobtrusive among [details] are often the most evocative, characteristic and even decisive. Exact details, an artful little nothing, make art.”

THE RECKLESS MOMENT. Columbia, 1949. James Mason, Joan Bennett, Geraldine Brooks, Henry O’Neill, Shepperd Strudwick, David Bair, Roy Roberts. Based on the novel The Blank Wall (Simon & Schuster, 1947) by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding. Director: Max Ophüls.

May 18th, 2013 at 8:28 am

This movie is excellent and a fine example of film noir. It’s been a few years since I’ve seen it and this review reminds me that it is time for another viewing.

May 18th, 2013 at 8:43 am

I saw THE RECKLESS MOMENT for this first time only last year. It was one of the few times after having searched for years to see a movie it surpassed my expectations. Highly recommended…if you can find a copy. I had to resort to the broken up version in six parts on YouTube.

As has probably been mentioned often any time this movie is discussed (I’m going to do it anyway) it was remade in 2001 with the daughter replaced by a gay son and Tilda Swinton as the protective mother. It’s called THE DEEP END, much easier to find on DVD, and equally good but with some problems.

May 18th, 2013 at 9:09 am

There is a DVD of the film offered for sale on Amazon. It’s described as a Korean import, but NTSC all regions, in English, with removable Korean subtitles.

It’s a bit pricey, though. Copies can be found on ioffer.com for about half the price.

I’ve never seen the movie. I will probably take the YouTube option myself.

May 18th, 2013 at 9:17 am

From Wikipedia:

Bosley Crowther’s New York Times 1949 review praised the actors but noted,

“But it isn’t all right with this picture. Although it is rather well staged, with credible location settings in Balboa and Los Angeles, it is a feeble and listless drama with a shamelessly callous attitude. The heroine gets away with folly, but we don’t think this picture will.”

May 18th, 2013 at 9:28 am

Many times I have read a Bosley Crowther review and disagreed with it. He seems to have had a limited understanding of movies and a habit of incorrectly judging films. This movie is not “…feeble and listless…”.

May 18th, 2013 at 10:26 am

I’d have to do some research on this to be sure, but I think Crowther’s track record on noir films was particularly bad.

May 18th, 2013 at 12:13 pm

Would be a good idea to have strict reviewers for reviewers.

Everytime the professional reviewer posts his thingy, there will be an echo.

Sometimes a BOOOM .

Anyway, interesting film noir, this here, I’ll see wether I can find it.

The Doc

May 18th, 2013 at 12:14 pm

I’ll buy an ‘h’ .

The Doc

May 18th, 2013 at 3:00 pm

Steve, I think that all of Ophuls’ American films have been screened on Turner over the last year or so but I’ll be happy to lend you my copy.

May 18th, 2013 at 5:51 pm

Walter

Thanks for the offer, but let me try watching it online first. If it’s as good as you and every one else says (except the fellow from the NY Times) I may want a permanent copy. (I am trying to cut back, but a collector’s instinct dies hard.)

Steve

May 18th, 2013 at 6:40 pm

Walker and Steve,

Crowther was probably the most consistently purblind critic of his times. Too bad Walter didn’t have his job!

May 18th, 2013 at 8:15 pm

Oh, so that’s what purblind means…

May 18th, 2013 at 8:56 pm

I was never much for Bosley Crowther but I have yet to see a Max Ophuls picture that worked for me. I enjoyed The Exile but that was an act of will for the subject matter and Doug Jr. As for The Reckless Moment, Joan Bennett was more than interesting, but the film, for me, was slow and self conscious.

May 18th, 2013 at 10:01 pm

As I recall (reinforced by a quick look at his Wikipedia entry) Mr. Crowther’s career at the Times ended abruptly with his decidedly negative opinion of BONNIE AND CLYDE in 1967. What I didn’t remember was his disdain for Joan Crawford. Quoting from his Wiki entry:

“Crowther also had a barely concealed disdain for Joan Crawford when reviewing her films, referring to her acting style as “artificiality” and “pretentiousness”, and would also chide Crawford for her physical bearing. In his review of the cult classic Johnny Guitar, Crowther complained that, “…no more femininity comes from (Crawford) than from the rugged Mr. Heflin in Shane. For the lady, as usual, is as sexless as the lions on the public library steps and as sharp and romantically forbidding as a package of unwrapped razor blades.”

Yipes. Now that is nasty.

I won’t know the right or wrong of it until I watch RECKLESS MOMENT for myself, but I have to admit in advance that I have often found James Mason’s performances to be “slow and self conscious,” to use your words, Barry, which I am pleased to steal from you. (Not always, but often.)

May 18th, 2013 at 10:50 pm

Thumbs up, Steve.

That piece on Joan Crawford is nasty to the point of unprofessional. If they let him go after that and the Bonnie and Clyde reviews it wasn’t because he was negative but way beyond. Yes?

May 20th, 2013 at 4:22 am

Barry,

I saw Ophuls’ LETTER FROM AN UNKNOWN WOMAN on TV when I was just a kid, and I still cry a little whenever it’s on. Whether I watch it or not. I just see it listed in the program guide and I get all misty.

May 20th, 2013 at 9:42 am

Dan:

I understand the feeling many of have re Letter From An Unknown Woman, but perhaps what you have is an allergy?