Fri 19 Jul 2013

A Western Review by Dan Stumpf (Book and Film): DECISION AT SUNDOWN (1955/1957).

Posted by Steve under Pulp Fiction , Reviews , Western Fiction , Western movies[15] Comments

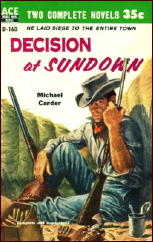

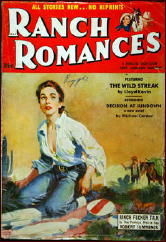

MICHAEL CARDER – Decision at Sundown. Macrae Smith, hardcover, 1955. Ace Double D-160, paperback, no date [1956]. Bound dos-Ã -dos with Action Along the Humboldt, by Karl Kramer. First serialized in Ranch Romances magazine, January 1955. (Part Three can be found online here.)

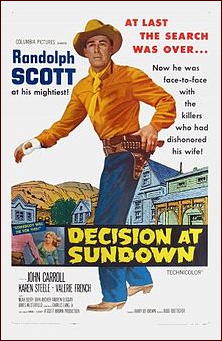

DECISION AT SUNDOWN. Columbia, 1957. Randolph Scott, John Carroll, Karen Steele, Valerie French, Noah Beery Jr., John Archer, Andrew Duggan. Based on the novel by Michael Carder (screen credit given to Vernon L. Fluharty). Director: Budd Boetticher.

My mention a while back of Jim O’Mara’s Wall of Guns elicited a comment from James Reasoner (a worthy western pen-slinger in his own right) revealing that O’Mara was actually one Vernon Fluharty, who also wrote westerns under the name Michael Carder, among them Decision at Sundown (Macrae Smith, 1955; originally serialized in Ranch Romances, January 1955) which two years later at Columbia studios was turned into one of Budd Boetticher’s most complex and least satisfying westerns.

The book Decision at Sundown bears some interesting similarities to Wall of Guns; in both a bitter loner rides into town seeking revenge, and in both he runs into a range fraught with intrigue: crooked locals grabbing for power, ranchers nursing long-simmering grudges, neighborhood bad guys, loyal friends and a woman who should hate him but finds herself strangely attracted to the handsome stranger (yawn).

The difference is that Wall of Guns was enlivened by some deeper-than-usual supporting players whose actions — whether short-sighted, passionate or surprisingly thoughtful — sent the book places where lesser tales don’t go.

In Decision at Sundown however, the ensemble remains depressingly stale: Tate Kimbrough, the town tyrant, is just a double-dyed rat; Lucy, his intended bride comes off like Daisy Mae on the printed page, too purely wholesome and impulsive to believe; Swede and Spanish, the hired guns are nothing but thug-uglies, and — and so it goes: the blowsy ex-mistress, the gruff doctor, grizzled rancher, doughty pardner … they all remain firmly in the cookie-cutter.

There’s a trace of depth as the plot develops and our hero suddenly finds his revenge turned laughable, but it’s quickly drowned in the shallow characters charged with putting it across.

When the novel reached Hollywood two years later, director Budd Boetticher and writer Charles Lang (story credit goes to Vernon Fluharty) picked up on that particle of originality and ran with it, adding some depth to the characters along the way and coming up with a B-western that if not completely satisfying, is at least original enough to remember.

The hero here is Randolph Scott, and when he rides into town it’s with the easy assurance of two decades of westerns behind him, abetted here by Boetticher’s graceful camerawork and feel for action. Unfortunately, he and the viewer get quickly mired in the story’s rather static complications, and the drama plays out in a few rather cramped and confining sets.

When one thinks of Budd Boetticher’s films, it’s with appreciation of his feel for characters framed against an open, rugged landscape, dealing warily with their issues and each other as they traverse hostile terrain that reflects some inner conflict. (Or as Andrew Sarris put it, part allegorical odysseys and part floating poker games.) But in this movie, we’re just stuck in a stable.

Stylist that he was, Boetticher managed a few fine moments, notably a couple of deliberately theatrical showdowns in the middle of Main Street, first with Andrew Duggan metaphorically stripping himself down for the performance, and later with John Carroll trying to hide his fears and live up to the Bad Guy’s Code of Conduct, murky as that may be.

In fact, Boetticher’s attention to this stock character almost brings the film to life. We first see Tate Kimbrough in standard attire for dress heavies in shoot-em-ups: fancy vest, dark coat, and the snide moustache worn by thousands of B-western baddies before him.

Then he starts to show some depth; he’s thoughtful and loving to his trampy ex-girlfriend, frank about himself and his past with his bride-to-be, and toward the end, when he has to go out and face Randolph Scott alone (a pre-doomed enterprise in films of this sort) there’s a rather touching moment when he confesses his fears to his ex-gal (a fine performance from Valerie French, who specialized in this sort of thing) but goes out there anyway.

I said this was a complex film and I meant it. I also said it was unsatisfying and I meant that too. In Westerns, action is traditionally cathartic, but in this one it simply becomes irrelevant, leading to an ending that Boetticher seems unprepared to handle.

There’s a lot of stage business between the dramatic climax and the actual ending of the film, and it dilutes the impact of what could have been a uniquely powerful Western. And that’s kind of a shame.

Note: To read Mike Grost’s extensive comments on this same film, check out his website here.

July 19th, 2013 at 7:25 pm

This and Dan Stumpf’s previous review of “Wall of Guns” are really informative.

I’ve never read any of Vernon Fluharty’s fiction. This article gives an interesting page-to-screen perspective.

I’ll be linking these two reviews soon to my Boetticher article.

The movie version of DECISION AT SUNDOWN is one of my favorites. It is gripping as story telling, having a complex plot that runs on several levels: the hero (Scott), the doctor, the women. This is unusual in its multi-focus. And full of admirable ideas about democracy.

Thank you for the link!

July 19th, 2013 at 8:01 pm

I’ve been to Mike Grost’s site and hate the subsequent gay reference to Scott and Buchanan Rides Alone. Further, if he thinks the Gandhi-like doctor carries the day he is flat out wrong. There is no day without the men of action and violence.

July 19th, 2013 at 9:08 pm

Right on my web site its says that victory over the dictators is “partly non-violent” and “partly violent”. It’s a complex situation. Still, it seems worthwhile to point out the non-violent aspects. These also appear in other Boetticher films like SEMINOLE and the MAVERICK TV series pilot WAR OF THE SILVER KINGS: three key works in his career. Boetticher is a complex filmmaker with many dimensions.

July 19th, 2013 at 9:46 pm

You are reading things into the product. The material is mechanical and the doctor a cipher — saved by adequate direction and above par performances from Scott, Beery, Carroll and Valerie French. As for Boetticher philosophically, he was clearly a man for hire and managed to make a fairly good job of it. The rest is for the Cinema Cahier crowd

July 19th, 2013 at 10:54 pm

The Wild West is a legend. But it certainly was wild, and , yes, it was in the west .

And it was VERY violent, full of hardship that normally does not get shown in the genre, because it is drab .

In real life, the West was won by Winchesters, knives, sticks, Colts, Remingtons, Sharps, stones, fists and incredible endurance. And luck. And brutality.

In the genre, be it books, be it movies, it is the man, not the pansy, who moves the story, shoots, hits, stabs, rides, and does what is right . Or wrong, then he is the villain.

Ghandi and ‘men’ with purses do not come into the picture .

I like my Westerns, as the are, books and movies,and am damn glad I don’t have to live there.

But as an escapist story from a world gone totally wrong, it is like food- GOOD food .

The Doc

July 19th, 2013 at 11:56 pm

According to my notes in Garfield’s WESTERN FILMS, I’ve seen this movie 4 times. At first I was disappointed by the fact that the movie is stuck in the town and studio. But everytime I’ve watched it, I’ve enjoyed it more and more. I now consider it outstanding, though I still don’t like the cramped town based settings.

What makes this movie a success is Randolph Scott. He had the ability and star power to make mediocre films enjoyable. I definitely consider him to be my favorite western actor though Joel McCrae is a favorite also.

July 20th, 2013 at 12:27 am

Mike Grost in his comments on Buchanan Rides Alone, bluntly states “Scott was gay in real life…” These rumors about Randolph Scott being gay have been around a long time and mainly were fueled by the fact that he and Cary Grant were close friends and lived together. But there never has been any real proof that Scott was in fact gay. I really don’t see how we can keep saying this as though it was some absolutely true fact.

Yes, they were friends. Yes, they lived together for several years and dated girls in their bachelor quarters. That’s about all we can say. Until we get some more definite proof, I don’t see how we can bluntly state that Scott was gay.

But concerning this gay rumor, I have a funny story to tell. Back around 1980 I bought my first VCR and started to watch my favorite movies. I was friends with a fellow collector from NJ named Harry Noble and we got into the habit of watching westerns together, including many starring his favorite actor, Randolph Scott.

One night after watching one of Scott’s films, my wife casually mentioned that there were rumors about Randolph Scott being gay. When I say that Harry turned white as a ghost, I’m not kidding. He had somehow never heard the rumor and he was stunned. Randolph Scott gay? He couldn’t get over it and refused to believe the rumor. He demanded proof and of course, there is no proof. Two guys living together and a bunch of rumors and gossip.

July 20th, 2013 at 12:51 am

All this rumoring is part of an activism that in the end is trying to prove that we all are gay .

Which simply is not so.

The Doc

July 20th, 2013 at 4:11 am

Some thoughts:

Dan Stumpf is right about landscape being brilliant in other Boetticher Westerns: SEVEN MEN FROM NOW and RIDE LONESOME come to mind. This aspect is badly missed in DECISION AT SUNDOWN, which is mainly town-set, after the opening.

But I also agree with Walker Martin: the more I’ve seen of DECISION AT SUNDOWN over the years, the better it looks as a film. It’s just a terrific movie.

It is news that DECISION AT SUNDOWN the novel was first printed in the pulp magazine RANCH ROMANCES. This is yet another reminder of how much the pulps have contributed to our culture.

Most of the great Western stars were straight: John Wayne, Joel McCrea, Tom Mix. But right in the middle of these is Randolph Scott.

Randolph Scott is one of the giants of Western film. He was a brilliant actor who created larger than life performances. He also worked with many of the best directors in Hollywood history: Allan Dwan, Fritz Lang, Andre de Toth (six films), Joseph H. Lewis, Budd Boetticher (seven films) and finally Sam Peckinpah in RIDE THE HIGH COUNTRY.

I have no inside information on Scott’s life, or Hollywood in general. But a lot has ben written about Scott, and has been summed up by his Wikipedia entry:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randolph_Scott

In recent years, accounts by personal friends of Scott have been published. These men were eyewitnesses to Scott’s life, and guests in his home. They describe Scott as openly gay among his close friends,

Of course, these men might be mistaken or lying. But the idea that Scott was gay is more than a rumor.

I was not trying to upset anyone, when I mentioned this in my web site. I know that ideas like this are upsetting to people like Harry Noble, who sounds like a nice person.

But it is also time for the contributions of all the great people who built up the United States to be recognized. Hard work should be honored. Our country was built up by white and black people, men and women, Christians and Jews, and straight and gay people.

July 20th, 2013 at 8:01 am

Georgina Washington, Gay Ben Franklin, Thomas Alva Edison, a great African American….

Let’s be honest- 99% of what the US, and for that matter, any other civilized nation, is today, was done by white men, who intheir absolute majority were straight, horribile dictu .

Abusing history as political propaganda is as old as history itself, starting with Mesopotamia, if not before.

It is NOT science, though .

Not truth, but Pravda .

The Doc

July 20th, 2013 at 9:28 am

I have a question that maybe somebody can answer. Why do we have to label great writers or great actors? Why do we say so and so the writer, who is gay. Or Randolph Scott the gay actor? We certainly don’t say John Wayne the straight actor, or Joel McCrea who was straight, or Humphrey Bogart the straight…

Just asking.

July 20th, 2013 at 9:35 am

As I wrote before- it is propaganda with an agenda by certain groups.

Being straight is normal , contains the possiblity of producing offspring, and thus enable mankind to continue-for whatever good that does .

Outing, true, false or rumor, somebody as gay is mostly gay activism directed at-see above.

Don’t get me wrong and label me homophobiac- but the avtivities in the last five to ten years, including the ”right” to adopt (other peoples’) children (human beings mostly NOT gay), and so on, can be seen from different perpectives.

And are starting to have a different effect, than was intended .

Political correctness and propaganda rightly ,and often, become a laughing stock, if nothing else.

Read- Pravda . And the likes .

The Doc

July 20th, 2013 at 9:42 am

11. Walker, for the same reason people like to read biographies. People are interested in people, who they were, what they did, what they believed in.

July 20th, 2013 at 10:33 am

Quoting Wikipedia is absurd. Rather then address the Scott issue, and I did know many people who knew him, have a look at The Self-Styled Siren’s most recent article that deconstructs Wallace Beery’s entry — instructive. My thought: SElf-Editing means no editing. A disgrace.

July 20th, 2013 at 10:39 am

A little more on this “gay” crap. The people I knew who knew Scott included Tony Martin and Cyd Charisse, Louis Hayward, Valerie French and Charles Lang of this film. There is on the Scott-Boetticher collection and comment made in anger on-screen by Budd in which he refutes the gay rumor by calling it “Bull Shit”. Of course, all these people are now gone, but there are recorded interviews with Cary Grant’s wives, and of course aa book by Dyan Cannon, which demolish these rumors.