Thu 3 Apr 2014

Mike Nevins on ERLE STANLEY GARDNER and Much More!

Posted by Steve under Columns , Mystery movies , Reviews[6] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

I could have sworn I’d read all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels decades ago, but when I recently pulled out The Case of the Singing Skirt (1959) from my shelves nothing in it struck me as familiar.

Club singer Ellen Robb is framed for theft and fired after refusing to help casino owner George Anclitas and his partner Slim Marcus trim wealthy Helman Ellis in a crooked poker game. Mason visits the casino and threatens Anclitas with a recent appellate decision holding that in a community property state like California a gambler’s spouse can recover any money the gambler lost.

Later Ellen finds a Smith & Wesson .38 in her suitcase and, fearing that Anclitas is out to frame her for something more serious than theft, goes to Mason again. In her presence, Mason happens to have a phone conversation with another lawyer in which he cites several cases holding that if a person is shot by two different people and could have died from either wound, only the one who fired the second shot is guilty of murder.

Without telling Ellen, Mason switches the gun she found in her bag for another of the same make and model that he happens to have in his safe. That evening he and Della Street secretly hide the gun he took from Ellen in the casino. Then Ellis’s wife Nadine is found shot to death — twice — aboard the couple’s yacht.

The police find the switched gun in Ellen’s possession and arrest her. Ballistics tests prove what seems impossible on its face: that the switched gun fired at least one of the fatal shots. In the courtroom scene, which takes up almost half the book, a third gun enters the picture and Mason eventually exposes some stupendous weapon-juggling.

Anthony Boucher in his review for the New York Times (September 27, 1959) called Singing Skirt “one of the most elaborate problems of Perry Mason’s career, with switchings and counterswitchings of guns that baffle even the maestro… This is as chastely classic a detective story as you’re apt to find in these degenerate days.â€

True enough. After finishing the book I whipped up a document which traces the wanderings of all three .38s and, unless I messed up somewhere, seems to establish that all the weapon-switching rhymes. (This document gives away so much of the plot that I won’t include it here, but if you’re interested, follow this link to a separate webpage.)

But if Ellen had told Mason all she knew, the truth would have been obvious before the preliminary hearing even began. Why didn’t she? She had promised the real murderer she wouldn’t! Gardner’s need to camouflage this silliness explains why he jumps into court almost immediately after Ellen’s arrest, leaving out any subsequent conversations between Mason and his client.

And if that aspect of the plot isn’t silly enough, how about the woman, never seen before, who marches unbidden into the courtroom at the end of Chapter Fourteen and confirms Mason’s solution?

Gardner once said: “[E]very mystery story ever written has some loose threads… After all, on a trotting horse who is going to see the difference? The main thing is to keep the horse trotting and the pace fast and furious.â€

Well, I’m not sure that every mystery ever written has plot holes, but far too many of Gardner’s do. Nevertheless he remains a giant of the genre and one of the most important lawyer storytellers of the 20th century. Which is why he gets a chapter to himself in my next book.

It’s called Judges & Justice & Lawyers & Law: Essays on Jurisfiction and Juriscinema and will be published later this year by Perfect Crime Books. At least six of its ten chapters deal with matters that should interest readers of this column: three on major American lawyer fiction writers (Melville Davisson Post, Arthur Train and, of course, Gardner) and another three on a trio of notable law-related movies (Cape Fear, Man in the Middle, The Penalty Phase).

The longest chapter in the book is called “When Celluloid Lawyers Started to Speak†and covers law-related movies from the first years of talking pictures, many of which have a crime or mystery element.

If you happen to groove on Westerns as well as whodunits, there are also chapters on law-related shoot-em-ups from the 1930s but after Hollywood began strictly enforcing its Motion Picture Production Code (July 1, 1934) and on what I like to call Telejuriscinema, which means law-related episodes of TV Western series from the Fifties and Sixties.

I expect this gargantua to run close to 600 pages, the sort of book Harry Stephen Keeler once described as perfectly designed to jack up a truck with. As more information becomes available I’ll report it in future columns.

Since one of the dozens of movies I discuss in the Celluloid Lawyers chapter may have played a role in Gardner’s work, I may as well close this column with a page or so from my book, as a sort of sneak preview of things to come.

In the early Perry Mason novels, which were heavily influenced by Hammett and especially by The Maltese Falcon, we are allowed to see only what happens in Mason’s presence. But soon after the Saturday Evening Post began serializing the Masons prior to their book publication, scenes with other characters taking place before Perry enters the picture became commonplace.

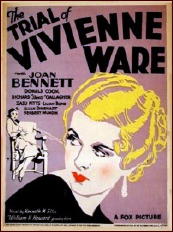

Where did Gardner get this notion? Quite possibly from a fascinating but little-known movie dating from the early years of talkies. The Trial of Vivienne Ware (Fox, 1932) was directed by William K. Howard from a screenplay based on Kenneth M. Ellis’ 1931 novel of the same name.

It opens with the title character (Joan Bennett) and her fiancé, architect Damon Fenwick (Jameson Thomas) going to the Silver Bowl nightclub where Vivienne is insulted by Fenwick’s former lover, singer Dolores Divine (Lilian Bond).

After taking Vivienne home, Fenwick returns to the club to pick up Dolores. The next day Vivienne sends Fenwick a letter she comes to regret. Several hours later the police arrest her for his murder. Representing her is attorney John Sutherland (Donald Cook), who is also in love with her — an element we never find in a Perry Mason novel.

The trial, perhaps the most swift-paced in any movie, begins with a mountain of evidence against Vivienne. One: On the morning after the nightclub scene she visited Fenwick’s house, walked in on Dolores in sexy pajamas eating breakfast with him, and stalked out furious. Two: Immediately afterwards she sent Fenwick a letter which might be construed as threatening.

Three: Her handkerchief was found near Fenwick’s body. Four: A neighbor claims to have seen her entering Fenwick’s house that night. Vivienne denies being anywhere near the house at the time of the murder but Sutherland doesn’t believe her. Nevertheless he puts her on the stand and she testifies as follows.

One: Her letter to Fenwick was meant to break their engagement, not to threaten him. Two: She must have dropped her handkerchief during her breakfast visit to Fenwick’s house. Three: At the time of the murder she was at a hockey game which she left early because she felt ill.

The district attorney (Alan Dinehart) cross-examines her so ruthlessly that she breaks down and sobs that even her own lawyer doesn’t believe her. At this point we find ourselves in the juristic Cloud Cuckoo Land that most Hollywood law films sooner or later enter: the prosecutor calls the defense lawyer as a witness! (How many times has Hamilton Burger pulled the same stunt with Mason?)

Changing Vivienne’s plea from not guilty to self-defense, Sutherland testifies that he attended the hockey match with her and, when she left early, followed her to Fenwick’s house. On the next day of trial Sutherland proceeds as if he were still pleading his client not guilty. First he calls witnesses who put Dolores Divine at Fenwick’s house at the time of the murder.

Then he calls Dolores herself, who testifies — as dozens of characters in Mason novels would do after her — that she found the body and said nothing about it but isn’t the murderer. (The film isn’t clear about this but apparently Vivienne, like so many of Mason’s clients, had done the same.)

I won’t delve any further into the plot but at the end of the picture spectators are roaring, flashbulbs blazing, lawyer and client embracing, and the jury returning a verdict of — well, can’t you guess? All this in less than 60 minutes!

We’ll never know if Gardner saw this movie, or perhaps read the novel it was based on, but the resemblance between the pattern here and that of so many middle-period Masons is remarkable.

April 3rd, 2014 at 9:10 pm

I understand that considering the length of your future book you are desperately looking for more material but…

Has anyone done a book on TV fictional lawyers? Along with cops and doctors the fictional lawyer has been a mainstay of TV since the beginning. From the early beginnings with such lawyers as John J. Malone to today’s SUITS it seems every type of lawyer has appeared at one time or another. Yet the most remembered remains the original Raymond Burr as Perry Mason.

April 4th, 2014 at 12:21 am

I’m not sure that this is the book you’re wishing for, Michael, but it may come close:

http://www.amazon.com/Lawyers-Your-Living-Room-Television/dp/1604423285/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1396588646&sr=1-1#reader_1604423285

April 4th, 2014 at 5:55 am

Mike,

Always enjoy your writing, but “Judges & Justice & Lawyers & Law: Essays on Jurisfiction and Juriscinema” seems to me like a less than best-seller title. Have you considered calling it “The Trial Games”? or “Harry Potter and the Jury of Death”? Or maybe just “Star Wars”?

You’ll thank me some sweet day…

April 4th, 2014 at 8:07 pm

By ’59 Gardner was wearing down a bit so it’s no surprise this one has some hasty bits of misdirection to keep the reader from noticing the holes. Like all of Garner’s works it is basically his favorite plot, Cinderella.

Quite possibly an ur Mason preliminary and possibly seen by Gardner. It would be nice to add it with Gardner’s own law practice Randolph Mason and Skin O’ My Tooth as Mason forerunners. Since you did the piece on Mr. Tutt did Gardner ever discuss Train or Tutt as forerunners to any extent?

April 5th, 2014 at 5:50 pm

2. Steve, the books is on Kindle so I checked out a sample. It looks inviting including the chapter on Perry Mason by “some one who’s name seemed familiar.”

I tend to lean more to histories and encyclopedias due to my fondness for the forgotten, but the book looks worth reading.

March 22nd, 2021 at 9:01 am

[…] Francis M. Nevins at Mystery*File compares this film to how Erle Stanley Garnder wrote his similarly fast-paced Perry Mason mysteries. […]