Thu 31 Jan 2019

A Book! Movie!! Review by Jonathan Lewis: Len Deighton: THE IPCRESS FILE (1965).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[14] Comments

LEN DEIGHTON – The Ipcress File. “Harry Palmer” #1. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1962. Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1963. Fawcett Crest, US, paperback, 1965. Reprinted many times.

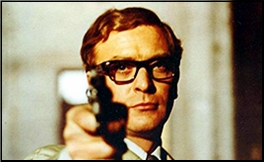

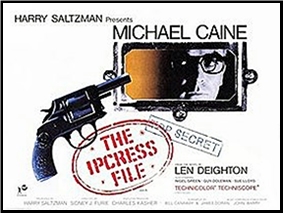

THE IPCRESS FILE. Rank Films, UK, 1965. Universal, US, 1965. Michael Caine (Harry Palmer), Nigel Green, Guy Doleman, Sue Lloyd, Gordon Jackson, Aubrey Richards. Based on the novel by Len Deighton. Director: Sidney J. Furie.

The screenwriters of the stylishly downbeat film The Ipcress File made the correct decision by introducing the notion of the eponymous file to the audience in the first half of the film’s running time. One structural problem in Len Deighton’s otherwise exceedingly compelling work of espionage fiction is that it’s not until the very tail end of the text that the author discloses what “IPCRESS†really means and how it fits into all that has transpired.

Somehow it lessens not only the impact of the word, but also the terrifying possibilities it portends for both the story’s protagonist and Western democracy as a whole.

To no one’s surprise, particularly those who are familiar with tropes from the spy genre, IPCRESS is an acronymm in this case for “Induction of Psychoneuroses by Conditioned Reflex under Stress.” That makes perfect sense, since Len Deighton’s work is Cold War fiction at its best. It is also fundamentally a thriller about mind control, particularly the West’s fear that the Eastern bloc as well as its more dogmatic and revolutionary Maoist cousins would develop a means of reprogramming Westerners into docile communist agents.

In the movie adaptation, British agent Harry Palmer (Michael Caine) comes across the word IPCRESS fairly early on during his investigation into the disappearance of a British physicist. He’s not sure what it means, but when a colleague who uncovers the true meaning of the word is murdered, he knows that he’s up against individuals willing to destroy people psychologically for the sake of their ideology or money or both.

Fundamental to the story is Palmer and how he fits, or alternatively doesn’t fit, into the mold of a spy. A military officer with a troubled past and a penchant for insubordination, Palmer is the anti-James Bond. He’s working class and lives a far from glamorous lifestyle. There are no exotic locales filled with beautiful women, yachts, or sports cars for him.

While the novel features sequences in both Lebanon and the South Pacific, the filmmakers made the right call and set the movie entirely in London, emphasizing the city’s persistently gray sky and its foreboding industrial spaces. Caine, with his Cockney accent and devil may care attitude, is a perfect fit for the role. Audiences must have agreed for Caine reprised the role in two other Palmer films in the 1960s: Funeral in Berlin (1966) and Billion Dollar Brain (1967).

In both the novel and the film version of The Ipcress File, Palmer’s investigation into the man allegedly responsible for both kidnapping and reprogramming British scientists so that they would be unable to work eventually leads him straight into the lion’s den. He gets captured and is forced to endure the mind control techniques that have wreaked havoc on some of England’s finest scientists, figuratively turning their brains into mush.

This is where the film gets psychedelic, very much akin to a scene toward the end of The Venetian Affair (1967), a movie similarly about communist brainwashing techniques, in which Robert Vaughn’s character is subject to an equally sinister method of mind control at the hands of a villain working for Communist China.

Sidney J. Furie’s direction, with his use of strange, unsettling angles, lends the film a disquieting feel. There’s not a lot of sunlight on display here, either literally or metaphorically. Palmer’s not doing his duty for Queen and Country as much as he is for his pay check and to avoid a military prison for transgressions he committed while serving in Germany.

In this film everyone is expendable and no one can be trusted. John Barry’s jazzy score gives this cynical and bleak alternative to the James Bond franchise a hip London vibe without the heroic fanfare.

January 31st, 2019 at 8:00 pm

The only critique I ever had of the novel was Deighton’s insistence on having the two intelligence bosses dueling over his anonymous agent named Dawlish and Dalby. The point they are opposite sides of the same coin is overshadowed by the reader trying to keep them apart.

Other than that it is a great book and a stylish film (the best of the Harry Palmer film series, though the best of the books is probably FUNERAL IN BERLIN).

One of the things I especially want to credit Sidney J. Furie for is finding a visual way to create the important use of documents and offical reports in the book to give it a feel of reading an intelligence dossier and not just a spy thriller. It’s no easy trick to recreate that on screen and still deliver a stylish thriller, but he does so with no little help from a well crafted script, the perfect cast (Nigel Greene and Guy Doleman are ideal foils to Caine), and the John Barry score that is in an entirely different style than his James Bond film music.

And Michael Caine himself deserves no little part of the credit as well, since most of the business he brings to the film is at best suggested by the much drier character in the book. Caine took a few tacks from Deighton himself to fill Harry in, actually creating his own character as much as playing Deightons.

As FLeming made Bond a tad more Scottish after seeing Connery so Deighton expanded the character of his his anonymous hero after seeing Caine’s performance.

January 31st, 2019 at 9:40 pm

Back in the mid-60s my wife and I were both in grad school, and we went to at least one movie and week, sometimes two. THE IPCRESS FILE came first, as I recall, followed almost immediately by ALFIE. I’ve been a fan of Michael Caine ever since. Two movies as unalike as they could be, and he was mesmerizing in both of them. May his craeer go on forever!

January 31st, 2019 at 10:02 pm

WARNING: Nearly Total Irrelevance.

This has to do with John Barry’s Ipcress File theme music.

Or at least the opening riff of it.

You remember:

BONG-BONG-BONG-BONNGG!

bling-bling-bling-blinngg!

BONG-BONG-BONG-BONNGGG!

hmmmmm-hm-hm-hmmmm-hm-hm-hmmmmmmm …

… you remember …

See, I didn’t see Ipcress when it first came out.

I heard that riff for the first time in the fall of ’65.

WGN-TV, Channel 9 in Chicago, had launched The Sherlock Holmes Theatre, a weekly showcase of the Universal Holmes pictures with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce.

The hook was that Ch9 had engaged Basil Rathbone as in-person host for the series.

Of course, there was that thing about there only being ten Universal Holmes movies (plus the two earlier Fox pix); Ch 9 filled out the season with their other whodunit asset, Charlie Chan (mainly Monogram, but it counted).

Whatever: sometime in ’65, Basil Rathbone came to Chicago to tape intros, outros, and in-betweenos for a full season of Holmes Theatres.

WGN built a reasonably impressive studio set for Rathbone (well, it sure looked impressive on a small B/W console): fireplace, wood paneling, props and stuff for Rathbone to talk about in the in-betweenos, etc. – all introduced with that Ipcress riff (they never went past that in any of the broadcasts).

WGN only did one season’s worth of Sherlock Holmes Theatre; the absence of more material was an obvious factor here.

When Basil Rathbone died in 1967, Ch 9 repeated a few of the Holmes Theatre shows, with the Rathbone material intact.

They only used Holmes movies; the Charlie Chan shows were bypassed (pity; I never got to see those, and I always wondered what Basil had to say about Mantan Moreland …).

To this day, I wonder if WGN kept any of these tapes; most likely they didn’t, and more’s the pity.

No matter; fifty-plus years on, whenever I hear the Ipcress File music, I think – not of Michael Caine – but of old Basil Rathbone, introducing those old Holmes movies, with which he had obviously made his peace over the years.

As I said above, irrelevant, but I never miss a chance (or excuse) to tell this one.

So There Too.

January 31st, 2019 at 10:24 pm

Is this it, Mike?

January 31st, 2019 at 11:23 pm

My brief Goodreads review of the novel:

The mixture of high literary language and postwar UK slang and pop culture in Deighton’s first novel is fresh, sometimes startling, and probably now requires annotation. He wants you to know that he can write, and you do know it.

January 31st, 2019 at 11:26 pm

I re-read the book last year, and found it slow going.VERY slow going. On the other hand, as you noted, the film is quite stylish, and I really enjoyed the performances by Nigel Green and Guy Doleman.

February 1st, 2019 at 12:23 am

My favorite Michael Caine, Peachy Toliver Carnahan, not the film, but his work in it.

February 1st, 2019 at 10:36 am

That would be THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING that you’re referring to, Barry. It’s one I’ve never seen. I should have, and I don'[t know why I haven’t.

February 1st, 2019 at 12:19 pm

Steve:

Almost.

That’s from an album John Barry made on his own.

WGN used the film soundtrack recording; they started with a sting fanfare from the library, then the BONGs (a bit twangier than the version here), then the Hmms with a lower clarinet sound (I think; I’m not a musician).

They began with a shot of the roaring fireplace, then panned across the den-set to a drawing room setup with Basil Rathbone, book in hand, ready to introduce that week’s feature.

Rathbone was in his uniform of the time, a blue with white pinstripes double-breasted suit of approximately early-’40s vintage (same suit every week, indicating that he shot them all in a very few sessions).

As I mentioned above, I didn’t get to see many of these (Monday nights in ’65, my family was watching Andy Williams). My loss.

Truth is I’ve never actually seen Ipcress File in its entirety.

I hear it’s not bad … 😉

February 1st, 2019 at 12:31 pm

Whether you’re a musician or not, you have a better ear than I do, Mike.

But it looks like this version will have to do for now for anyone who’s never heard it before.

February 1st, 2019 at 2:37 pm

Steve, the picture is good enough, though imperfect. But, the first half and the ending make it all worthwhile. You probably know that Gable and Bogart had been intended to play the leads by John Houston. Life got in the way on that one.

February 3rd, 2019 at 12:20 am

Barry,

Over the years there were a number of proposed teams for a film of the Kipling story including at various times Richard Burton and Richard Harris and I’ve even heard Errol Flynn and Stewart Granger.

Great as Connery and Caine are, Plummer makes a wonderful Kipling.

February 3rd, 2019 at 12:33 am

David,

All of those make sense to me. Gable and Bogart were actually in discussion with Huston, but Bogart died, and later Gable. I agree with you, Plummer is definitive, but Flynn and Granger make me smile in anticipation. I would go.

April 6th, 2020 at 11:36 am

[…] that memorable a work. Unlike Caine’s other spy thrillers – The Ipcress File (1965) (reviewed here) comes to mind – this one just doesn’t have nearly the same level of excitement or style. […]