Wed 8 Apr 2020

A Western Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: CHARLES NEIDER – The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones // ONE-EYED JACKS (1961).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction , Western movies[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

CHARLES NEIDER – The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones. Harper & Brothers, 1956. Crest #368, paperback,1960. University of Nevada Press, trade paperback, 1992.

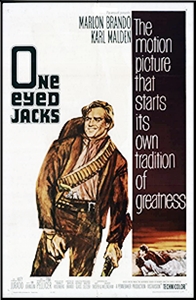

ONE-EYED JACKS. Paramount, 1961. Marlon Brando, Karl Malden, Pina Pellicer, Katy Jurado, Ben Johnson, Slim Pickens, Timothy Carey and Sam Gilman. Written (at various times) by Guy Trosper, Calder Willingham, Sam Peckinpah and Rod Serling. Directed by Marlon Brando.

Like Day of the Outlaw, a book and film that grow widely dissimilar. But where Day’s incarnations are excellent, these are great.

Charles Neider wrote a highly acclaimed biography of Mark Twain, and I read somewhere that he then set himself to a similar work about Billy the Kid, but gave it up after years of research and wrote the novel The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones instead. His own introduction to a later edition tends to refute this story, but I like it anyway. In fact, Neider’s prose is very much like Twain’s. No surprise that, but it’s Twain in a nostalgic, elegiac tone, as the narrator, Doc Baker, looks back on youth and friendship now gone.

Doc, however, is only the narrator. The subject of the book is a Billy the Kid figure, here named Hendry Jones, and Neider manages to convey second-hand the attraction and fear the character evokes in those around him: the easy charm, generosity, sexual magnetism and murderous nature of a man who lives only in the moment. Make no mistake, Hendry Jones is one of the great figures of Fiction and he’s right at home in a great novel.

No wonder then that the character and the book would attract an actor of Marlon Brando’s caliber. And even less wonder that, having bought the novel and been given carte blanche on the film, Brando would feel compelled to re-shape it to his own psyche as One-Eyed Jacks.

The result is nothing like the book, but there’s no arguing with the beauty of the thing. Brando directs himself with a knowing narcissism that makes for powerful cinema and plenty of just-plain-fun movie moments. He knows his own strengths, and writes and plays to them, with quietly-mumbled lines like “Don’t be doin’ her that way,†shot with all the impact of a stray bullet.

For a self-indulgent egoist, Brando is surprisingly generous with his supporting players. At the top of the list, Karl Malden’s portrayal of venal hypocrisy is as compelling as Brando’s forthright knavery. Slim Pickens and Pina Pilar play lustful and lustee, arrogant and innocent, with real feeling, and Ben Johnson, my personal favorite, damnear steals the whole show as a bloody-eyed bank robber partnered with Brando.

And oh yes: Timothy Carey, the sine qua non of quirky movies, got most of his scenes deleted (he was fired for causing trouble on the set and demanding that his salary be doubled), but survives long enough to try to back-shoot the Star — never a good idea in a Western.

I read that tidbit in another book: A Million Feet of Film: The Making of One-eyed Jacks (2019) by Toby Roan. It’s full of information, with snippets from just about every biography, magazine article and gossip column on the subject, some quite juicy. I would have appreciated more insight (much of the material seems self-serving and rather suspect), but there’s no gainsaying the research and effort that went into this, and there are gems of information here, including:

One of my favorite moments in the film is when Rio (Brando) catches up with his betrayer (Karl Malden) after five years in a Mexican jail and months of searching. The scene is set for a shoot-out… and they sit down and lie to each other in an extended scene, perfectly written and played!

So imagine my surprise to learn that this was largely re-shot without Brando, when the Studio heads decided it made Malden’s character too sympathetic. I read the original dialogue here and looked at the scene again… and I had to agree with the Suits that this works much better! Credit goes to editor Archie Marshek and Karl Malden, for a seamless and captivating bit of Cinema.

April 9th, 2020 at 7:20 am

It hasn’t been a conscious effort, but I don’t believe I’ve ever watched a Marlon Brando movie all the way through. After reading this review, I have begun to wonder if I’ve been wrong about that all these years.

April 9th, 2020 at 8:47 am

This one, and The Chase, both of some interest, are marked by masochism. Both were unsuccessful

April 9th, 2020 at 9:14 am

This is actually my second favorite western, after “Rio Bravo”.

April 9th, 2020 at 8:06 pm

The book sounds interesting, but honestly I could not get through the pretentious mess of a film despite the sometimes gorgeous look. It tanked to pretty general bad reviews but became something of a cult classic.

Great review though Dan, because you nail what it is you like about the film and why, and that’s more important than than how the rest of us view it.

April 12th, 2020 at 12:01 pm

Saw the movie recently and appreciated the underlying tension that was established early and maintained through the rest of it. Malden was excellent.