Mon 18 Jan 2021

A Western Movie Review by David Vineyard: UNION PACIFIC (1939).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[11] Comments

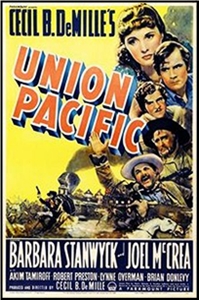

UNION PACIFIC. Paramount Pictures, 1939. Barbara Stanwyck, Joel McCrea, Robert Preston, Brian Donlevy, Akim Tamiroff, Lynne Overman, Robert Barrat, Henry Kolker, Anthony Quinn, Lon Chaney Jr., Stanley Ridges, Evelyn Keyes, Regis Toomey, Joe Sawyer, J. M. Kerrigan, Richard Lane, Fuzzy Knight. Screenplay by Walter DeLeon, C. Gardner Sullivan, and Jessie Lasky Jr.; adapted by Jack Cunningham from a story Ernest Haycox (also uncredited on the screenplay, along with Frederick Hazlitt Brennan). Directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

One of Cecil B. DeMille’s better epics, and probably his best Western, the story of the race to Ogden, Utah, by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroad centers on the efforts of trouble-shooter Jeff Butler (Joel McCrea) in the employee of General Dodge (Francis McDonald) to prevent murderous gambler Syd Campeau (Brian Donlevy) from sabotaging the advance of the title railroad for crooked Chicago businessman A. M. Barrows (Henry Kolker), who plans to fund the Union Pacific, buy Central Pacific stock and make a fortune selling the former short when it fails by his machinations.

It’s based on a tight well written story by Ernest Haycox, ironically whose story “The Last Stage to Lordsburg†was filmed as Stagecoach the same year. Cecil B.DeMille and John Ford both using your work as a source the same year was a pretty heady place for a pulpster to be, and it showed when Haycox, already in the slick, soon graduated to the Book Club circuit and best seller list too.

Complicating things is the three-way romance between Irish postmistress Molly Monahan (Barbara Stanwyck, beautiful, though you can take some issue with her Irish accent), daughter of engineer Monahan (J. M. Kerrigan) who drives the General McPherson, charming rogue Dick Allen (Robert Preston), Butler’s former wartime friend and Campeau’s partner, and Jeff.

As usual the history in any DeMille epic is only there to back up a good deal of myth and legend and a certain amount of flag-waving and or Bible-thumping, but it is pretty good corn here with lots of riding, shooting (a memorable shootout between McCrea and Anthony Quinn, “It’s a good thing you keep that mirror clean.â€), fighting (a good fight between McCrea and Robert Barratt), and romance between Stanwyck and charming Preston and reticent stalwart McCrea (“I loved him from the first time I hit him.â€).

When Allen steals the railroad payroll Molly covers for him, but forces him to return the loot in exchange for marrying him which puts him on the wrong side of Campeau.

Akim Tamiroff is Fiesta and Lynne Overman, Leach Overmile, Butler’s seedy comedic companions. They were similarly teamed, only on opposite sides, in Northwest Mounted Police. Preston played similar rogues in the former and in Reap the Wild Wind (also with Overman). Virtually everyone in the film from son-in-law Quinn to the least bit part is from a DeMille regular (Monte Blue, Elmo Lincoln, Frank Lacteen, and Iron Eyes Cody all are uncredited and look for a young Richard Denning).

There is an old saw about the basic kinds of Western, and this one fits clearly in the Empire building category of silent classics like The Iron Horse and Covered Wagon. It’s a bit old fashioned even for 1939, considering it competes with Stagecoach.

Molly marries Dick to save Jeff, but Campeau talks and Jeff arrests him the day of their wedding. She helps him escape, but when Dick hides out on Molly’s car on the way to Laramie he discovers she really loves Jeff just before they are attacked by a Sioux war party stirred up by Campeau.

However you view the whitewashing of Western history or the exploitation of Native Americans it is a splendid sequence visually with DeMille at his best right down to the cavalry coming on another train.

There is some sympathy for Native Americans expressed here, more than in Stagecoach where Ford uses them only as a force of nature.

That rescue train crossing a burning trestle is beautifully shot, right down to the comic relief when Tamiroff’s mustache is burned off (Overman: “I never liked it in the first place.â€)

There are a number of scenes like that in the film including Irish track layer Regis Toomey murdered by Anthony Quinn speaking of the light as a shadow passes over his dying face and a weeping Stanwyck holds him in her arms on the saloon floor.

Another nice set piece features Jeff and Monahan pushing the General MacPherson across a snow bridge to cut around a tunnel they can’t complete in time. “’Tis the first time for an engine to run on snow, and if he don’t like it, I’ll put snowshoes on him.â€

Yes, it is corny, right down to the use of “My Darlin’ Clementine†as a running theme throughout the film even as a funeral dirge for Monahan when the first attempt at crossing the snow proves fatal, but it still has cinematic power in the old Hollywood tradition. It may be model work, and obvious to us today, but it was state of the art in 1939.

Finally at Promontory Point Jeff, Molly, and Dick are reunited as the golden spike is driven in with Campeau planning revenge.

Jeff: He’ll be waiting for us Molly — at the end of track.

Just before the vintage railroad becomes a gleaming modern engine cutting across America as the music swells.

I’ll grant some of you have grown too sophisticated for this to work, some will find a million reasons to find offense at something or other, and I don’t fault you if you do, but even recognizing its flaws, it is splendid film making, a classic Hollywood cast and creative talents working at the top of their form, and Western mythologizing in the epic mode at its best. I still think there is something to be said for the lost arts that made it possible that is worth recognizing and applauding whatever the social flaws or the lack of modern sophistication.

I hope I never reach the point I can’t still respond to this kind of film a little like the kid lying on the living room floor looking up at a twenty-seven inch black and white screen, eating popcorn, and watching this unfold between commercials. I hope every one of you still has some films that bring back something like that for you.

There was a reason Hollywood was called the Dream Factory.

January 18th, 2021 at 9:18 pm

Marvelous review, David. You got hold of it by the tail and shook. DeMille must be my personal least favorite filmmaker of the classic era, but not when he made Union Pacific. The performers are the key, and Stanwyck, the sound era’s greatest actress who see work I dislike, turns on the charm. The only other film of her that has her unique quality that I personally favor, meet John Doe. Different, but the same. Robert Preston was born a good actor, but McCrea was not, and I am inclined to believe this was his first of many fulsome performances.

Now about Cecil B. Recently I revisited Samson and Delilah; do not do it. Unconquered is even worse.As for The Greatest Show on Earth, movie stars flying through the air, just great, but the thing never stops and plays like a canceled television series. I saw then all as a child. Phooey on youth.

January 18th, 2021 at 10:32 pm

McCrea and Stanwyck teamed a few times, perhaps at their best in THE GREAT MAN’S LADY with Brian Donlevy in one of his best performances.

UNION PACIFIC and WESTERN UNION always strike me as the best of the Empire building Westerns. I’ve watched them in tandem a few times and they compliment each other.

I like both NORTHWEST MOUNTED and UNCONQUERED, but only because I view both of them as Technicolor serials more PERILS OF PAULINE than serious films. Not a serious bone in their heads, but splendid visuals and good bits by many involved, and I am an admitted sucker for Paulette Goddard in a wooden tub taking a bath.

January 18th, 2021 at 10:39 pm

Goddard taking a bath is sweet and lovely, also she seems to be having fun with it. I had the misfortune of reading Neil Swanson’s novel prior to seeing the film, and I liked it, but …Now, as for Western Union, it is a favorite, so much so I acquired a copy of Zane Grey’s novel. Not bad, but nothing like the film, not even the names are the same. It does have a sensual edge, whereas Lang’s film or Zanuck’s is more romantic. Either way, Randolph Scott shines, as does Dean Jagger and Virginia Gilmore. An interesting side bar: It took longer for Fox to film the story than Creighton and his crew took to string the wire.

January 19th, 2021 at 12:59 am

I have no such expertise on westerns as is wonderfully on display in this chat but I have seen my humble share of deMille titles. He always does seem to be applying a deMille ‘formula’ to whatever he does. I’ve gone out of my way to be receptive to him. Usually …left wanting. In my private opinion the only way to tell a spectacle is to depict characters small, and personal, and human. But it does sounds like (in this case) as if Stanwyck et al kept things just exactly at that ideal level. My ears have perked up. I recollect *seeing* bits-and-pieces of this picture over the years, but never the whole thing all the way through. It’s to my disadvantage, I’m sure. But of all the western archetypes, ’empire’ and ‘Alleghenies’ (easterns)…oil booms … likely draw me in the least. Also any western where ‘women take over’ [‘Westward the Women’, etc]. TRAIN -based westerns though, at least have that one huge gorgeous merit. Never anything wrong with a train in a western. But Conestogas and Studebakers and single-trees and even Phaetons…awk. Oh well grand movie review!

January 19th, 2021 at 8:37 pm

Lazy Georgenby,

In this particular DeMille epic, and the two others mentioned the actual historical figures take a back seat to fictional ones so that scenes with Colonel Dodge or General Grant or a brief voice over by Lincoln are shadings and not dominant features (Dodge has yet another major role in the Errol Flynn Western Dodge City). Of the three mentioned this is by far superior and I would argue superior even to DeMille’s other better known films.

Barry,

I read the Swanson book and enjoyed it too, but after seeing the film, so my expectations were different.

January 19th, 2021 at 11:07 pm

DeMille raised vulgarity to a high art.

January 19th, 2021 at 11:54 pm

Now, Dan, just vulgar and surprisingly acceptable to a wide audience, but his silent films, much stronger

January 20th, 2021 at 12:13 am

I’m of very agreeable mind on the topic of deMille. I’m completely open to having my opinion –my appraisal –my en-capsulization of Cecil B. DeMille’s style improved and bettered, by those who track his arc more closely than I have. I’m not ag’in him. ‘Nothing succeeds like success’ as the saying goes. And deMille sure had his druthers.

Actually, (something which slipped my mind until this moment) I am a whole-hearted fan of at least one sprawling deMille epic. ‘The Buccaneer’ (1938) is one of my all-time most-savory adventure films and also stands perennially as my favorite ‘pirate’ film.

I haven’t thought about ‘circus’ films in a while –but yea –I might nominate his ‘greatest show on earth’ as my favorite “circus” film. It can stand for the present until I mull it over further. ‘Nightmare Alley’ or other carnival-centric films might edge it out.

Anyway: ‘Union Pacific’ …what a cast!

January 20th, 2021 at 12:20 am

“My wife’s ancestors came West in covered wagons –and if you’d seen her ancestors, you’d know why the wagons were covered!”

–Shelton and Howard

January 20th, 2021 at 2:47 am

The ultimate carnival film is surely Tod Browning’s “Freaks”, Lazy Georgenby.

E.C. Bentley’s view:

Cecil B. De Mille

By a great effort of will

Was persuaded to leave Moses

Out of the Wars of the Roses.

October 26th, 2022 at 3:25 pm

The story is actually quite complicated, as Jeff and Dick oscillate between enemies, rivals and comrades, and Molly’s feelings for the pair are not simple. Molly seems remarkably unfazed by the deaths of her father and husband. Were audiences a bit quicker on the uptake back then?