Sun 28 Mar 2010

A Movie Review by David L. Vineyard: SEVEN DAYS TO NOON (1950).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[7] Comments

SEVEN DAYS TO NOON. British Lion Films, 1950. Barry Jones, Olive Sloane, André Morell, Sheila Manahan, Hugh Cross, Joan Hickson, Geoffrey Keen, Victor Maddern. Screenplay: Roy Boulting and Frank Harvey. Original Screen Story by Paul Dehn and James Bernard. Directors: John and Roy Boulting.

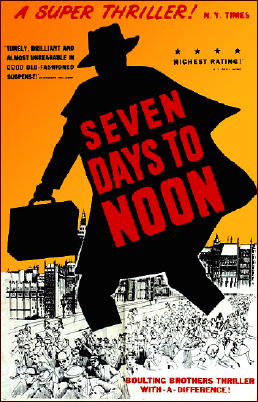

This taut little suspense film is one of the best of its kind ever made. With an Oscar-winning original story by Paul Dehn and James Bernard (best known for composing many of the scores for the Hammer horror films) and a screenplay by co-director Roy Boulting and novelist Frank Harvey (White Mercenaries), the film is an achingly suspenseful exercise in nuclear extortion as a soft-spoken scientist holds London hostage amidst a nationwide manhunt, done in a variation of the docu-noir style of many American films of the period.

The film also won the British Oscar, the BAFTA, for best picture and John and Roy Boulting received best directing nominations from the Venice Film Festival.

Barry Jones (Brigadoon, Demetrius and the Gladiator, War and Peace) is the scientist, Professor Willington, who disappears from his job at a nuclear research facility and leaves a letter to the Prime Minister (Ronald Adam) stating he will destroy London in seven days at noon on the seventh day unless his demands for nuclear disarmament are met.

The world was made in seven days, and London will be destroyed in seven days unless mankind stops the madness of nuclear research is the disturbed professor’s demand.

Superintendent Folland (Morell) of the Yard and Stephen Lane (Hugh Cross), the professor’s research assistant and future son-in-law, head the nationwide manhunt once it is discovered that along with the professor a suitcase nuclear device is missing. (They didn’t exist then and still don’t now, but where would these films be without them?)

The film focuses less on the hunt itself than on Willington as he flees to London and interacts with a handful of people including a somewhat flowsy Cockney woman (Olive Sloane) and his landlady (Joan Hickson — Miss Marple). The professor’s ideals are contrasted with the ordinary real people they threaten in a small Cockney neighborhood — not saints or even the salt of the earth, but human beings unaware their very existence is threatened.

As the pressure intensifies and the noon deadline approaches, London is evacuated and the shots of the empty streets are both haunting and striking. Meanwhile the authorities close in and the professor’s mental state deteriorates more rapidly. The final confrontation in a church is both evocative and tense.

Solid as this is as a suspense film, there is more to it, which perhaps explains why it has a resonance still today. Jones is neither an egotist nor a monster, but a kindly and gentle man driven to the ultimate act of terror by the daily horror of the work he pursues. Morell is presented as a human and understanding policeman, and everyone involved seems weighted down by the horror of both the potential destruction and the morality involved.

Willington is a madman and a terrorist, but a real effort is made to understand his mental breakdown and stop him without killing him; something it becomes increasingly obvious they may not be able to accomplish.

Seven Days to Noon is something more than a suspense film, an early example of the anti-nuclear movement, then in its infancy, and also a meditation on the beginnings of the arms race that would reach its high (or low) point with the Cuban Missile Crisis. The film bothers to ask important questions, and to force viewers to ask who the real madman is — the professor unbalanced by the horror of his work, or the society blithely ignoring the apocalypse under its nose.

There are no easy answers here. Horrible as the Professor’s threat is it may be less horrible than the future he wants to prevent. The film never suggests such terrorism is justified, only that to an unhinged mind it may seem so.

This story has been done countless times since, but seldom this well. There is an interesting contrast with a 1953 American film from Fred Sears and Ivan Tors, The 49th Man, an altogether pulpier (but entertaining) version of the A-bomb in the city story with a few nice paranoid twists and a good performance by John Ireland as an undercover operative.

But this film is neither shrill nor melodramatic; it is quiet and powerful, and it may be more relevant today than it was when it was made sixty years ago. It also offers a fascinating look at a London still marked by the bomb craters from WW II, at a time when you could actually conceive an orderly evacuation of a city the size of London.

Note: If you go to IMDb you will discover this is the first original film score by noted British film composer John Addison.

March 29th, 2010 at 9:30 am

David — One of the very few George Clooney films in which I liked his performance was THE PEACEMAKER (1997), another flick about nuclear terrorism.

Normally Clooney’s smugness bleeds through, but in this one it’s appropriate since he happens to be the smartest man in the room when it comes to the situation they’re in.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0119874/maindetails

“Take the shot!”

March 29th, 2010 at 10:19 am

Paul Dehn later went on to write most of the “Planet of the Apes” sequels.

March 29th, 2010 at 6:10 pm

Mike

I liked PEACEMAKER too. The nuclear bomb plot has gotten a lot of use over the years. I even recall an episode of LOU GRANT dealing with a possible home made nuke in LA.

Dozy

Dehn also wrote THE DEADLY AFFAIR based on John LeCarre’s CALL FOR THE DEAD with James Mason as Charles Dobbs(George Smiley), THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD, GOLDFINGER, and MOULIN ROUGE. He won three writing Oscars and five nominations.

March 30th, 2010 at 5:19 am

I saw this film on a bootleg dvd last night and enjoyed it. I do not consider this film noir but Keaney’s BRITISH FILM NOIR GUIDE gives it a high rating.

March 30th, 2010 at 9:14 am

I’ve not seen the movie, but from David’s description and review, that it’s a noir film wouldn’t have been the first thought that would have come to mind. In fact I hadn’t at all till you mentioned it was in Keaney’s book, Walker.

It’s another example of the mindset that says that any crime or spy movie filmed in black and white back in the 1950s must be noir.

Borderline, I suppose.

Every time I’ve intended to tape this from TCM, something’s gone wrong. Either I forget, or if I remember, I program the VCR wrong, or something equally inept.

— Steve

March 30th, 2010 at 5:11 pm

By the way Steve, I have this on a British *official* dvd release, except I can’t find it among my stacks of films. Fortunately I also have it on a excellent quality bootleg. So you can order it from Amazon UK. Olive Sloane, as the aging dancehall girl, steals every scene she is in.

March 30th, 2010 at 9:27 pm

Walker

Olive Sloane does give a great performance.

I’ve never considered this noir although it does borrow a little from the docu noir or procedural noir style, but I don’t think anyone involved intended anything along the lines of a noir film.

Steve

Do see this one. It is one of essentials, rated four stars in most film books. While I would not rate it as noir, there are touches of German Expressionism, notably in the scenes which you reproduced in the review of Barry Jones in the darkened city surrounded by wanted posters with his face all over them — something that almost certainly was a reference to Fritz Lang’s M (though the stories are different and the points the film make different, there are some parallels between the two films).

What is a bit noirish about this one is how it tells the big story through small stories and characters caught up in the manhunt and the terror, though Sloane is far from a femme fatale.

And I do think it falls in that no man’s land where it can just narrowly be squeezed into a book on noir if only because it is such an important film and so well done someone just wanted to include it. It’s also included in many books on science fiction, which it isn’t despite that suitcase nuke.

It does have more in common with Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass serials though than film noir as far as I’m concerned in the way it deals with the story. It’s closer to that or THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE than most film noir in both its approach and its style.

This is a powerful film though, much closer to films like ON THE BEACH or DR. STRANGELOVE which came a good decade later than to film noir from the period it as made in. For a film made in 1950 it asks the kind of questions films didn’t ask regularly and as well until the late fifties and sixties.