Sun 29 Apr 2007

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES RUNYON, by Ed Gorman.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Interviews[3] Comments

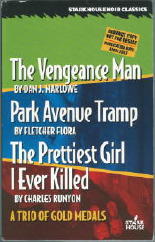

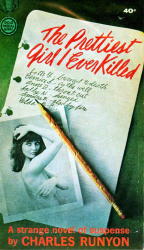

Stark House will publish its first three-fer this summer – three Gold Medal novels long in need of reprinting. I wrote the introduction to Charles Runyon’s The Prettiest Girl I Ever Killed, a masterful suspense novel that puts Runyon in the top ten of GM writers in such company as Lawrence Block, John D. MacDonald, Charles Williams, Vin Packer, Richard Stark, Malcolm Braly and a handful of others.

At the time I wrote the introduction I was told that Runyon was dead. Not so. He’s very much alive, and here’s an interview I recently had with him via email.

[Note: This interview previously appeared in three installments on Ed’s blog. Links at the end of this M*F blog entry will lead you to a complete bibliography of Charles Runyon’s fiction and an article he has written about a book that’s never been published, Dorian-7. — Steve]

● The obvious mystery to those who were following your career – when did you stop publishing and why?

However, the hiatus stretched on, and teaching did not blend with writing as well as I had hoped. Writing was still my preferred profession, but the path back to publishing was a rocky one, and nobody laid down a red carpet for me any more than they had at the beginning. Somehow the word got out that I had “passed on” in 1987, and the thought intrigued me, much as it once intrigued Tom Sawyer. What if I tried to reenter the field, not as an older writer reentering the field after a long lay-off, but as a fresh new face with reams of new ideas? However, thanks to you, Ed, that experiment has now been abandoned, or left to others to carry out.

● Can you give us a sketch of your life?

So we come full circle; 60 years later I am back in Texas. The intervening years included army service in Korea, Germany and Indiana, J-school at Missouri University. I just missed a job on the National Geographic and instead went into industrial editing. It was either that or poetry which paid nothing. While working for Mr. Rockefeller’s old outfit in Chicago an agent to whom I had been paying readers’ fees for five years – Scott Meredith – suddenly started making sales.

I lost no time in quitting my job and announcing that I was now a full-time writer. With a new baby and no income, I borrowed a lakeside cabin and sat down to write my first book. After sending it off to my agent, I took off for the West Indies, found an almost deserted island, and lay back to await the gentle shower of royalties. It didn’t quite happen that way, but it was only a few months before the book sold to Ace; my reaction was to charter a yacht and take the wife and kid on a tour of the islands. I returned to New York suntanned but broke, still expecting the gilded life of a best-selling writer.

● How about a sketch of your publishing career? Was writing something you’d always wanted to do?

● Do you recall your first sale?

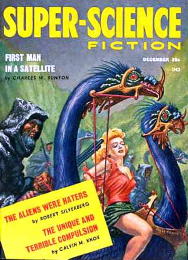

● Which gave you more satisfaction as a writer – science fiction or crime novels?

● What was the genesis of The Prettiest Girl I Ever Killed?

Actually, the story is not as bizarre as it may seem; my home town is near the little town of Skidmore, famed as the home of the hog-stealer, arch-bully, pedophile and murderer MacElroy, who was finally “executed” by a shotgun blast in full view of thirty townspeople. Not a single one of those citizens stepped forward to identify the shooter. Someday, I may get around to doing that book.

● Prettiest Girl is invariably likened to the novels of Jim Thompson but when I reread it recently my take was that there is a fundamental difference between your book and just about anything Thompson wrote. Your killer in control of himself – unlike many of the Thompson protagonists who seem hard-wired to be at the mercy of themselves – and he’s even a bit droll and sardonic at times. In other words, he can stand back and look at what he’s doing objectively.

The cumulative effect of this subtly but powerfully underscores his madness. Given the verities of paperback originals, this was an original approach. Did you think of it that way? Or are you even conscious of your writing decisions? Evan Hunter always said that he tried not to analyze what he was doing. He was afraid it would hamper his spontaneity.

That’s the reason I usually get in a few weeks of total leisure between novels; the creative energy needs time to rise to a level where I can begin pumping again. I think Evan Hunter is right in not analyzing his methods; the creative imagination is a shy, faery creature, and doesn’t like the cold light of appraisal.

● Sometimes you sound almost dismissive of your crime fiction. Your science fiction seems to be your true love. Are you unhappy when people say they prefer your crime fiction to your sf?

But I can date exactly when my preferences changed; in 1967 my younger brother was murdered, and the whole messy scene got involved with the stupidity of Vietnam and the decay of the courts, with the result that the murderer walked out of the courtroom smirking. This was too similar to the stuff I had been doing, and although I had many projects in the works, I never felt good about doing that sort of killer-oriented thing again.

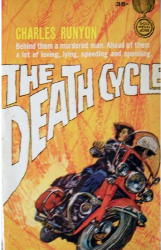

● You’ve written some of the most remarkable opening chapters in suspense fiction. The first five thousand words of The Dead Cycle, for instance, put me in mind of The Doors’ “Riders on The Rain.” Except that where the song is from the innocents’ point of view, this is from the Riders pov. There’s a mythic quality – almost of the old west – of the robbery gone wrong, an elderly clerk shot dead by one of the Riders, and them now desperately trying to get to the Mexican border.

This is so much more realistic than much of the neo-noir we see today because the turf is real and you know this turf, the small-town Midwest. But it’s the underbelly of the Midwestern small town you usually use. Was this intentional given that it’s the setting of so many of your Gold Medal novels?

● The Black Moth, which is set on a college campus, is a notably different private eye novel in that the protagonist is a PI masquerading as a professor. But even here, in a more refined setting than you usually use, the writing stays hard as hell. Your books are proof that tough guys don’t have to swagger or be violent to prove that they’re tough. They’re hard asses and no less so when they don academic robes. Was Black Moth based on your early experiences teaching college courses?

● What was your best career experience?

● What was your worst?

● You mentioned that you’ve been writing a science fiction trilogy. Have you given any thought to a crime novel?

● Do you read contemporary writers? If so, name a few you feel are notable.

John Updike’s suspense novel, The Terrorist, brings out his talent for deft characterization and subtle plot turnings, as well as being as timely as the morning paper. John Grisham is another old-timer who’s still eminently readable; The Painted House is one I recommend. Taking the whole field as my bailiwick, I’ll mention Trial, by Clifford Irving, Skins of Dead Men by Dean Inge, and Acceptable Losses by Irwin Shaw. I’d also recommend The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley. Though it’s not a genre novel, it’s a fascinating story and well-written.

● Which of your novels would you most like to see reprinted and why?

Also, there was one I wrote under the nom de plume of Mark West, which was published under the unforgettable title: Object of Lust. Another rush job, done to the background music of a wolf growling outside the door, but I think it’s worthy of another shot at the gold ring. If you recall the old limerick beginning: “There once was a hermit named Dave …” you’ll have an idea of what it’s about. And finally there’s my first one, The Anatomy of Violence, which still holds my interest despite a klutzy romantic element.

—

Charles W. Runyon: A Bibliography

March 30th, 2008 at 3:04 pm

I am glad to see you are not dead after all. I am the son of Virginia Hillix. We met briefly when I was about 14. Your influence on Tom Wright and subsequently on me has had a significant,and I feel a very positive effect on my life. I am sad to report that Tom died about ten years ago of renal failure brought on by many years of untreated high blood pressure. My mother died eight months ago of lung disease. I know that both were happy to have known you.

December 8th, 2008 at 10:56 pm

I don’t think I read much of your stuff but I’ve always remembered your name as the author of Remember Me, Peter Shepley. One of my all time sf favorites.

September 11th, 2010 at 6:16 pm

i am surprised that no one ever mentions “Soulmate”; i met you – i am not sure how – but you were a guest in my home in philadelphia in the early 70’s and i believe the book had just come out or was just coming out and do i remember correctly that you received the poe award for it? i unpacked a box of books and voila – i’ve been carrying it around for all these years……..