Wed 2 Mar 2022

SF Stories I’m Reading: THEODORE STURGEON “Agnes, Accent and Access.â€

Posted by Steve under Science Fiction & Fantasy , Stories I'm Reading[2] Comments

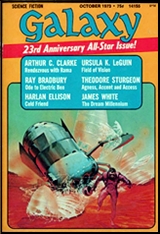

THEODORE STURGEON. “Agnes, Accent and Access.†Short story. First published in Galaxy SF, October 1973. Reprinted in The Best from Galaxy, Volume II, edited anonymously by Ejler Jakobsson. Collected in Case and the Dreamer, Volume XIII: The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon (North Atlantic Books, 2010).

This is the second of three short stories in this issue of Galaxy that I’ve been reading, ignoring the two long serial installments by James White and Arthur C. Clarke that take up a full two-thirds of the magazine. As far as ISFDb knows, the story has appeared in only two other places, which seems strange to me, as it’s a good one.

When a company who stock in trade is the information retrieval business, it seems strange that they have to hire an outside consultant when problems arrive internally: requests from departments of the firm are being replied to with very incorrect responses. His way of investigating: to sit outside the president’s office ostensibly waiting for an appointment but in reality watching the very efficient secretary, named Agnes, working at her desk throughout the day.

This story was written in 1973, long before Siri and Alexa came along, but if science fiction could ever have been said to predict the future, and the describe the problems that come along with it, this is a story that fits the bill to perfection. Adding even more to the enjoyment of the tale is the fact that Theodore Sturgeon was a flows along.

Examples. This one line sentence, a mere throwaway in fact, sums up a fact that you might not of thought of yourself, but once read, you say, “Of course.â€

Or how about this longer passage, describing only the office itself where the consultant is waiting and observing:

March 2nd, 2022 at 9:07 pm

Sturgeon wrote so effortlessly it is often hard to catch him writing. His work almost feels organic, not crafted or worked.

With so much good work it shouldn’t be too surprising a good story or two slip through the cracks of all the great ones.

March 2nd, 2022 at 9:15 pm

Most of his work was of shorter fiction, writing perhaps less than a half dozen novels. Some authors have their own niche and stick to it. Ed Hoch was the same way, but Sturgeon, a lot more polished. If a would-be writer ever read a Sturgeon story, he might give up at once.