August 2008

Monthly Archive

Sun 31 Aug 2008

WITCHCRAFT. Lippert Films / 20th Century Fox, 1964. Lon Chaney Jr, Jack Hedley, Jill Dixon, David Weston, Diane Clare, Yvette Rees, Victor Brooks. Director: Don Sharp.

The year, 1964, is the same as the previous movie reviewed here on the blog, Devils of Darkness, with which it was recently paired in a recent DVD release, and both were filmed in England, but nonetheless there’s an ocean of difference between them.

I don’t mean geographically. Devils was filmed in glorious color; Witchcraft was filmed in even more glorious black-and-white. The story in Devils appeared to have been put together at the spur of the moment; Witchcraft has a single focus — that of a witch being resurrected from the dead — and seeking revenge. The latter in particular makes a good deal of sense to me, if I’d been buried alive as a witch some 300 years or so ago.

Beginning with the first scene, we (the viewer) are caught up in the story, as a bulldozer makes its way through an ancient cemetery, uprooting underbrush, dirt and (of course) gravestones, making way for a new development. Then we see the outraged Morgan Whitlock, (played by Lon Chaney, Jr., and the only American actor in the film) shaking his cane in the air and saying that there will be the equivalent of hell to pay.

He’s right. Later the same evening a gravestone is pushed aside and Vanessa Whitlock climbs her way out of the ground. She’s played by a skeletal-looking Yvette Rees, who manages to be authentically shivery scary without being actively icky repulsive, a fact you can perhaps agree on by seeing the photo located to the right.

It turns out that Vanessa’s wrath is not only directed toward the partner in the construction firm that desecrated the graveyard, but toward the family of the other partner, Bill Lanier (Jack Hadley). There has been a feud between the Whitlocks and the Laniers ever since Vanessa’s non-death, mostly fueled by resentment by the Whitlocks for being ousted from their family home.

There’s also a Romeo and Juliet forbidden romance to keep the plot going — a return from the grave not being quite enough — so even without a whole lot of gore, there’s enough story to entertain us (the viewer) for the full 79 minutes of running time.

I included Victor Brooks in the list of credits, even though he doesn’t have much time on the screen. He plays essentially the same role as he did in the later Devils of Darkness, that of the local police inspector who’s called in when the deaths begin to pile up. This time he’s totally puzzled; by the time he appeared in Devils, he was a whole lot quicker in picking up on the fact that the supernatural was involved.

Too bad the same can’t be said about the characters in Witchcraft, if fault be found anywhere in this film. As usual, they do the most stupid things, such as leaving themselves (or their wives, grandmothers and girl friends) totally alone and vulnerable while all of these strange events are going on. It’s par for the course, of course, but I mention it because perhaps seeing characters doing stupid things bothers you more than it did me, this time.

One last thing. The director of Witchcraft was Don Sharp. I didn’t mention him in my review of The Devil-Ship Pirates, but he was also at the helm of that film, and as it happens, it was the very same year, 1964. A few years later (1968) he also directed a few TV episodes of The Avengers, of which in terms of all-around watchability, this movie reminded me of a lot.

Sun 31 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Max Allan Collins:

JAMES M. CAIN – Serenade. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1937. US Paperback editions include: Penguin Books #621, 1947; Signet 1153, 1954; Bantam S-3864, 1968; Vintage, 1978.

Film: 1956, with Mario Lanza and Joan Fontaine.

Though lesser known than his more famous The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, Serenade is equally a masterpiece. Most of Cain’s best work is of novella length, but Serenade is an exception; a wider canvas is required for this more ambitious work with its subject matter that was daring even for Cain.

The operatic undertone of Cain’s work comes to the fore here as an opera singer who loses his voice regains it by spending a night of lust and love with a Mexican whore in a deserted church during a thunderstorm.

When John Howard Sharp returns to New York City and his singing career, the healing prostitute, Juana, is at his side; but they are soon faced with a threat from the past, the man whose homosexual liaison with Sharp had caused the singer?s traumatic loss of voice. In James M. Cain, there can only be one solution to such a situation: murder.

But murder in Serenade isn’t born of greed and petty self-interest as it is in other Cain novels. The man and woman who share this sexual adventure are admirable and self-sacrificing. Their love is noble, and their tragedy is the deepest, most affecting in all of Cain.

Cain wrote Serenade and his two other masterpieces in the 1930s; but his later, lesser (if interesting) works have tended to dilute his reputation. He is easily the peer of Hammett and Chandler, however, neither of whom wrote with Cain’s unabashed passion.

Among his better later works are Past All Dishonor (1946) and The Butterfly (1947); they are, characteristically, in the first person. Mildred Pierce (1941) is the best of Cain?s third-person works. Several other completed novels are among Cain?s papers, and remain unpublished.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright ? 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sat 30 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Max Allan Collins:

JAMES M. CAIN – Double Indemnity.

Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #16; paperback original, 1943. First published in Liberty magazine in 1936 as the eight-part serial “Three of a Kind.” First hardcover edition: included in Three of a Kind (Knopf, 1944) with “Career in C Major” and “The Embezzler.” Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and paperback, including Avon #60, 1945 (shown).

Film: 1944, with Barbara Stanwyck & Fred MacMurray; adapted for the screen by Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder.

James M. Cain wrote of “the wish that comes true … I think my stories have some quality of the opening of a forbidden box, and that it is this rather than violence, sex or any of the things usually cited by way of explanation that gives them the drive so often noted.”

Double Indemnity employs this same technique, already displayed in The Postman Always Rings Twice, with dazzling ease. Cain, making a quick buck writing a magazine serial in 1936, did not realize it at the time, but he was at the top of his form. Employing skillful, scalpel-like first-person narration, Cain tells his tale of love and murder from the point of view of a lover and murderer.

Insurance man Walter Huff becomes embroiled in a plot to kill a beautiful woman’s husband. In addition to the sexual and financial incentives, Phyllis Nirdlinger manages to play upon Huff’s boredom and his pride – he knows the insurance game inside and out, and figures with his expertise he can beat it.

The husband is murdered, according to Huff’s plan, without a hitch. But Huff is dogged by Keyes, a claims agent who also knows the insurance game inside and out. Huff begins to realize Phyllis is untrustworthy and just possibly insane, and falls in love with Lola, the daughter of the murdered man by a previous wife, who had very probably been yet another murder victim of Phyllis’s.

Double Indemnity is a murder mystery turned inside out: We are forced inside the murderer’s skin, only to find it uncomfortably easy to identify with him, and then share his paranoia as the world crumbles piece by piece around him.

Huff is a white-collar worker and he’s smart – smart enough to sense early on just how major a mistake he’s made. His sense of his own frailty and wrongdoing makes him a truly tragic protagonist, as does his sense of loss: “I knew I couldn’t have her and never could have her. I couldn’t kiss the girl whose father I killed.”

Cain liked to explore the workings of businesses, and he never did it better than in Double Indemnity, through the characters of Huff and Keyes. But he also gave the pair an understated shared understanding of humanity (an aspect broadened in the widely respected Billy Wilder-directed, Raymond Chandler-scripted film version of 1944).

In their final confrontation, Keyes says to Huff (renamed Neff in the film), “This is an awful thing you’ve done, Neff,” and Huff/Neff only says, “I know it.” And when Keyes says, “I kind of liked you, Neff,” Huff/Neff says, “I know. Same here.”

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 29 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Max Allan Collins:

JAMES M. CAIN – The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1934. Paperback reprints include: Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #6, 1943; Pocket 443, 1947; Bantam, 1967; Vintage, 1978.

Films: 1946, with Lana Turner & John Garfield; 1981, with Jessica Lange & Jack Nicholson.

This brutal little blue-collar love story was a shocking, sexy, “dirty” best seller and set the standard for tough, lean writing. It taught readers (and writers) that dialogue could propel a story by its own steam (and steaminess) with (as Cain himself put it) “a minimum of he-saids and she-replied-laughinglys.”

From its famous first sentence (“They threw me off the hay truck at noon”) to its spellbinding final moments on death row, The Postman Always Rings Twice moves like a freight train, catching the reader up in a sleazy, unpleasant – and compelling – illicit love affair.

Drifter Frank Chambers. finds himself in a roadside eatery called Twin Oaks Tavern (the first of many double images). Nick Papadakis, the friendly Greek who runs the place, has a wife who “really wasn’t any raving beauty, but she had a sulky look to her.”

Soon Chambers is running the tavern’s gas station for the Greek; and by the end of chapter two, Frank and Cora have made a cuckold of him; by chapter four they are attempting Nick’s murder. And these are short chapters.

Incredibly, the adulterers engage not just our interest but our sympathy, our collusion. Their lust (“I sunk my teeth into her lips so deep I could feel the blood spurt into my mouth”) is contagious, and redeemed by the extravagance of their passion (“I kissed her … it was like being in church”).

Yet Cain pulls no punches: Their intended murder victim, Nick, is not unsympathetic; Frank genuinely likes Nick, and after Frank and Cora succeed on the second try and kill him, cries genuine tears at his funeral.

Frank and Cora – particularly Frank – are so out of control, so much smaller than the web of circumstance and human frailty in which they are caught up, that a strange sort of supportive interest develops for them. Cain feels for these small lovers who are doomed in so big a way.

And so do we. When in the aftermath of Nick’s murder and the faked auto accident that follows, Cora and Frank indulge in a manic orgy of sadomasochism and passion at the scene of the crime, we are caught up in the moment with them. As Frank says: “Hell could have opened up for me then, and it wouldn’t have made any difference. I had to have her, if I hung for it.”

Part of the enduring power of Postman is its evocation of the depression. Frank and Cora’s dream is the American one: They want a business of their own, a family of their own-simple goals that had been made so difficult in hard times. Their greed was small; their aspirations petty. Their love, and their crime, in James Cain’s tabloid opera, large.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 29 Aug 2008

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

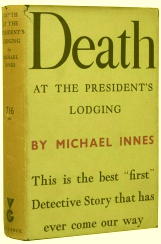

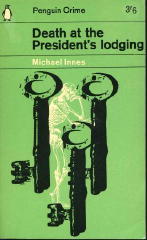

MICHAEL INNES – Seven Suspects. Berkley F1158, paperback reprint, November 1965. US hardcover edition: Dodd Mead, 1937. First published in the UK as Death at the President’s Lodging, Victor Gollancz, hardcover, 1936. [Other US paperback editions include: Dolphin, 1962; Penguin, 1984.]

Without a doubt, in terms of intelligence and general all-around erudition, Michael Innes has to be ranked in the top five mystery writers of all time. (I don’t know how you’d put this to a test, but I can think of only a handful I might start comparing him to, and the funny thing is, they’re all English.)

In the beginning, though, he seems to have been too intellectual for his own good. Seven Suspects was his first mystery novel, and in spite of the great start and the fine setup, to get through the middle portion of the book involves some very tough slogging, to use the vernacular, at least by contemporary standards.

The great start? Well, it’s not quite a locked room mystery, but it’s the next best thing. And speaking of which, what this (Berkley) edition of the novel needs, more than anything else, is a map, a map of St. Anthony’s College, where the President is found shot to death in his Lodging, with gardens and walls and locked doors all around, and only a limited number of keys with which to open them.

There could hardly be a greater contrast between the two officers of the law involved, deliberately so. The local copper is the prosaic Inspector Dodd, far more comfortable with tracking down a gang of burglars than a shrewd and wily killer who leaves a puzzling trail of enigmatic clues behind.

On the other hand, the nimble-witted Inspector John Appleby, sent down quickly by Scotland Yard, is perfect for dealing with the retinue of eccentric academics who never seem to speak before thinking twice (or thrice) about the implications of what they are about to utter.

Being a native Midwesterner by birth, American style, I have to confess that some of the doings in the aforementioned middle portion of the book, carried out by a small company of carefree undergraduates of the college, were intended to be funny, but not to me. To the average Londoner at the time, they probably were — and maybe even hilarious. (It took me a chapter or two of such antics, but I did finally get into the spirit of things.)

What is also true, as I came to realize toward the end of the book, is that not a single female appears who has a speaking part, and only one who’s in the book at all has more than a servant’s role. (In all truthfulness, it took Innes’s own observation of this patricluar fact for me to notice. Sometimes I really am slow.)

And so, this combination of dry academic humor and a decidedly noticeable lack of authorial interest in Appleby the person — that is to say his personal life, his worries and concerns — it all makes this Golden Age gem far out of the mainstream of the mystery world today.

But gem it is. There are some flaws — it’s a wholly artificial staging, of course — but the comings and goings the night of the murder, who did what when, and who saw what and who didn’t, whose voice that was, and whose it wasn’t, it’s a eye-popper and a mind-blower, and my head is still spinning.

A gem that needs some polishing, then, but for an academic exercise in the pure pleasure of plotting, very very few of the thousands of mysteries ever published come even close to topping this one.

— August 2002, slightly revised

Fri 29 Aug 2008

DEVILS OF DARKNESS. Planet Films/20th Century Fox, 1964. William Sylvester, Hubert Noël, Carole Gray, Tracy Reed, Diana Decker, Eddie Byrne, Victor Brooks. Director: Lance Comfort.

As a direct competitor to the horror films being made in England by Hammer Films and others at and around the same time, the early to mid-1960s, this mishmosh combination of devil worship, vampirism, witchcraft and necromancy — whatever’s convenient for the plot line at the time — simply has no legs to stand on.

Webster: mishmosh: a confused jumble, a hodgepodge.

American actor William Sylvester plays Paul Baxter, a stalwart British, almost professorial type whose vacation in Brittany is interrupted by three strange deaths of three fellow Englishmen (two male, one female) in conjunction with an isolated village’s unusual rites in a local cemetery.

His suspicions aroused, when he returns England planning to investigate further, but when the three coffins making the journey back with him mysteriously disappear, it makes his task all the harder.

Unknown to him, by the way, is the talisman that he found and now has in his possession. Belonging to Count Sinistre (Hubert Noel), the leader of the cult of devil-worshipers, the latter wants it back in the worst way.

And in vampire films, we know what that means.

From what I’ve learned about this film, it may be the first British vampire film to take place in modern times. And if this means including a scene of with many assorted mod people doing the Twist or Watusi in a garishly decorated apartment filled with smoke of many sorts, then so be it.

It makes them easy converts to cult activities of a more sinister sort, one supposes, including the wearing of red hooded robes and uttering various chants of servitude, standing in a circle in some grand manor’s basement.

Carole Gray and Tracy Reed play rivals for the Count’s hand, the former in a fine gypsy rage, the latter (a redheaded cousin of Oliver Reed) largely in a trance, although strictly as demanded by the script mind you. (She was high in the running to replace Diana Rigg in The Avengers. I’d have rather she had.)

It’s a talky affair, unfortunately, and surprisingly enough, even the inspector from Scotland Yard (Victor Brooks), seems all too willing to accept the supernatural at work, once he’s gained Baxter’s confidence and the latter reveals what he knows.

A couple of scary moments are to be found in this not very scary movie, no more. A rating of PG could easily be appropriate.

In summing up: pretty cheesy stuff, indeed, one designed perhaps for beginners in the genre, not long-time fanatics. The actors are fine. It’s the indecisiveness — and incoherence — of the story line that lets them down.

Thu 28 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Max Allan Collins and James L. Traylor:

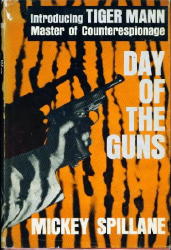

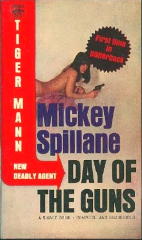

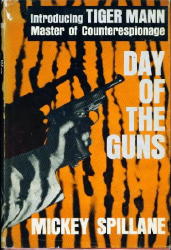

MICKEY SPILLANE – Day of the Guns.

E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1964. Signet D2643, paperback, April 1965. [Several later printings.]

Properly overshadowed by Mike Hammer, espionage agent Tiger Mann is the hero of Mickey Spillane’s only other series of mystery novels. Mann remains a pale shadow of the mighty Mike, a Bond-era reworking of the Hammer formula; but the first of the series has considered merit.

Tiger Mann is employed by an espionage organization funded by ultraright-wing billionaire Martin Grady, of self-professed altruistic, patriotic purposes. Chatting with a Broadway columnist in a nightclub, Tiger spots a beautiful woman who strikingly resembles a Nazi spy named Rondine who attempted to kill him years before.

Though he loved Rondine, Tiger has sworn to kill her should he encounter her again. The woman, Edith Caine, professes not to be Rondine, but Tiger refuses to believe her and sets out to learn what she is up to. Soon he is battling a Communist conspiracy, and in a striptease finale that purposely evokes and invokes the classic conclusion of I, the Jury, Tiger must face the naked truth about Rondine.

Day of the Guns is a fast-moving and fine example of Spillane’s mature craftsmanship; he has great fun doing twists on himself, as the conclusion of the novel shows. But this book – and, particularly, later Tiger Mann entries – lacks the conviction of the Hammer novels.

Tiger Mann is Mike Hammer in secret-agent drag: His style and world are Hammer’s; despite mentions of faraway places, the action is confined to New York. But while Hammer is an antiorganization man, Tiger, for all his lone-wolf posturing, is a company man. This goes against the Spillane grain.

The three other Tiger Mann novels are Bloody Sunrise (1965), The Death Dealers (1965), and The By-Pass Control (1966). Each declines in quality.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 27 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Bill Crider:

MICKEY SPILLANE – I, the Jury.

E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1947. Signet 699, paperback, 1948. [Many later printings.]

When Mickey Spillane published I, the Jury in 1947, Hammett’s first novel had been in print nearly twenty years and Carroll John Daly and Raymond Chandler were still writing. Yet there is little doubt that Spillane’s book was a seminal work of tough-guy fiction, inspiring hundreds of imitators in the booming paperback market of the 1950s. No one, however, was quite able to match Spillane’s unique combination of action, sex, and right-wing vengeance.

The main character of I, the Jury is Spillane’s most famous creation, Mike Hammer — tough, implacable, and prone to violence, with perhaps even a touch of madness. When his war buddy is murdered, Hammer swears to get revenge: “And by Christ, I’m not letting the killer go through the tedious process of the law.”

Hammer smashes his way through the suspects (“My fist went in up to the wrist in his stomach”) until he determines the guilty party, whom he has sworn to kill in exactly the same way his friend was murdered. Along the way, he meets the nymphomaniac Bellemy sisters, one of whom has a strategically located strawberry birthmark; Charlotte Manning, a beautiful psychiatrist; Hal Kines, the improbable white slaver; and of course he fends off the advances of Velda, his sexy, loyal secretary.

He finally confronts the killer in a slam-bang ending never to be forgotten by anyone who has read it, concluding with perhaps the best last line in all of Spillane’s books, most of which have memorable, melodramatic climaxes.

Spillane’s novels have been attacked for their violence and their vigilante spirit, and no doubt these things are present in the books. But Spillane is first and foremost a storyteller, and his stories, no matter how improbable, always work, pulling the reader along willingly or unwillingly into Mike Hammer’s violent world.

I, the Jury was brought to the screen in 1949, with Biff Elliott in the starring role. Like the novel, it emphasizes violence and has an ending to enrage the sensibilities of any feminist who happens to watch it.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 26 Aug 2008

THE LONG WAIT. United Artists, 1954. Anthony Quinn, Peggie Castle, Gene Evans, Mary Ellen Kay, Shawn Smith, Dolores Donlon, Charles Coburn. Based on the novel by Mickey Spillane. Director: Victor Saville.

In a comment that he left following my review of the movie The Guilty, based on the novelette “He Looked Like Murder,” Walker Martin commended me on comparing and contrasting the film version with Cornell Woolrich’s original story.

I wish I could always do it, but usually it doesn’t work out that way. If I’ve just seen the movie, the book is nowhere to be found. If I’ve just read the book, finding a copy of the film is another question altogether.

Case in point, and another small confession. If I’ve ever read The Long Wait as a novel, it was so long ago (50 years maybe) that if I did, I’ve forgotten it. And if I did read it, the other voice in my head says, how could I have possibly forgotten it?

This last statement was prompted by the post that appeared just before this one. If I ever read a book anything like the one Bill Crider talks about, I think it would have stuck in my memory forever.

Not being able to find my own copy of The Long Wait, I thought that Bill’s review would serve the purpose almost as well. Probably better, but I won’t tell him that.

But before I being telling you about the movie, you might want to take a look at a short clip of the movie I found on YouTube. It’s the opening few minutes, in which you see Anthony Quinn being picked up as a hitchhiker, the fiery accident that follows, and a brief glimpse of the next scene, with Quinn in a hospital with his hands completely bandaged.

He also has amnesia and no idea of who he is, where he was going, and more importantly, where he was coming from. A prankster, though, with hardly the best intentions in mind, sends him back to Lyncastle, where he’s known as Johnny McBride – and where also a wanted poster proclaims him wanted for murder.

If you read Bill’s review again, you’ll get the idea that the book runs generally along the same lines. I don’t see Anthony Quinn as a “Johnny McBride,” however. His face and that name simply don’t match. I don’t say that he’s miscast, exactly, but I also don’t see him as the girl magnet he becomes as soon as he returns back to Lyncastle. (The police, by the way, have a problem matching him up with their fingerprint evidence. Due to the accident he was in, he no longer has fingerprints.)

In any case, from here on in, I’ll be reviewing the movie, not the book. There is more actual violence in this film than in most noirs – with one early scene standing out in particular, when McBride is trussed up and about to be thrown into a 200-foot-deep quarry, and ends up alive – and the three hoodlums all dead.

And another one later which has to be seen to be believed – and I’ll get back to that later. There is also an elaborate detective story going on as well, or actually a pair of them. First of all, the question is, who’s the real killer? But the second, and the more interesting, is who of the four woman who McBride becomes involved with is his old girl friend, Vera West?

McBride’s memory is gone, of course, and since Vera’s had plastic surgery done before she came back, no one else knows who she is either. Well, one man knows, but he’s killed, shot to death early on. Working against McBride all the way is Servo (Gene Evans), the gangster who practically owns the town. (Evans was last seen by me as the leader of the pack of thieves doggedly hounding the trail of Clint Walker and Roger Moore in Gold of the Seven Saints, reviewed here back in July.)

You do have allow some license to the screenwriter in working all of this into a sensible plot, let alone go down smoothly. (My copy of the film is unfortunately one that originally had color commercials for a California used car dealer in it, and whoever cut them out did not do a very good job of it. Some transitions are jarring, and I am slightly suspicious of them, thinking that maybe some small bits and pieces have been removed.)

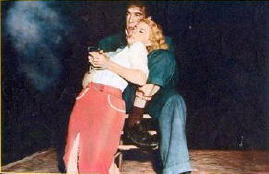

There is one long scene in this movie that makes definitely worth watching, even if all you can find is a crummy copy. That’s the one that comes toward the end, with Quinn as McBride tied in a chair in the middle of an empty warehouse, and Peggy Castle as Venus (one of the possible Vera’s) with her feet bound and her hands tied in front of her as she works herself slowly across the floor to him on her elbows, with Servo laughing and deriding her efforts the entire way.

Beautifully photographed in glorious black-and-white, with lots of deep shadows and contrasting areas of light, this is a scene that will stick in your mind for a long time. The movie’s hard to find copies of, but it does exist. It has some flaws, but I hope I’ve made you want to see it. I don’t think you’ll regret it.

PostScript: I sent an advance copy of this review to the previously mentioned Mr. Crider, hoping to come full circle, if possible, and let him compare the film (unseen by him) with the book. His reply, short but succinct: “The quarry scene’s in the novel, and the scene you mention at the end is (probably) much more violent in the novel, a real torture scene.”

I don’t know about you, but I think I’m going to have to find a copy of the book, and soon.

Mon 25 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Bill Crider:

MICKEY SPILLANE – The Long Wait.

E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1951. Paperback reprint: Signet 932, May 1952 [plus many subsequent printings].

The Long Wait, Mickey Spillane’s first non-series novel, is the author’s variation on the one-man- against-municipal-corruption theme as found in such novels as Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest. The Mike Hammer-like narrator/hero, whose name is either Johnny McBride or George Wilson (even he isn’t sure), returns to the town of Lyncastle to clear up a robbery-and-murder charge against McBride.

His motive, as usual in Spillane’s work, is revenge: One man is to get his arms broken, and one man is to die. Actually, a lot of people die before the narrator accomplishes his lofty goal, but not before he absorbs more physical abuse than seems even remotely possible.

And speaking frankly of credibility, it must be admitted that The Long Wait contains enough coincidence and enough improbable, even downright incredible, plot devices for four or five books. There is violence galore, too, and a lot of voyeuristic sex (the final scene is a rewrite of the striptease that concludes I, the Jury).

None of this affects the story adversely, however. Typically, Spillane pulls it off. The pacing and the fierce conviction of the narrative voice grab the reader and carry him relentlessly along. Spillane seems to have had a high old time writing The Long Wait, and the reader who is willing to grin, plant his tongue in his cheek, and go along with him is in for a hell of a ride.

Other nonseries books by Spillane with more or less Hammer-like heroes are The Deep (1961) and The Delta Factor (1967). The Erection Set (1972) and The Last Cop Out (1973) are Spillane’s only books with third-person narration.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Next Page »