August 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 31 Aug 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

A GENTLEMAN OF PARIS. Paramount Famous Lasky Corp., 1927. Adolphe Menjou, Shirley O’Hara, Arlette Marchal, Ivy Harris, Nicholas Soussanin. Screenplay by Chandler Sprague from the story “Bellamy the Magnificent” by Roy Horniman; titles by Herman Mankiewicz; photography by Hal Rosson. Director: Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

The cinematography by the noted Hal Rosson was compromised by the dark print that made some of the intertitles difficult to read.

This was also to be a problem with at least two other films, one of which was so severely damaged that the last reel was almost unwatchable. (More on this later.)

Adolphe Menjou is the dapper Marquis de Marignan whose complicated love life is managed with great skill by the apparently unflappable Joseph Talineau (Nicholas Soussanin), his butler and general manager of his household.

The arrival of the Marquis’ fiancee, Yvonne Dufour, taxes even Joseph’s talents, but all seems to be under control until Joseph learns that his wife (their marriage seems to be one largely of convenience from her point of view) is one of his employer’s conquests.

Stunned by the discovery, Joseph decides to destroy the Marquis by engineering a card game that appears to demonstrate that the Marquis is a cheat, a crime worse, in the eyes of society, than cheating with a friend’s wife. What begins as a frothy comedy of manners turns so dark that the only recourse for a gentleman is to take his own life.

The sudden reversal that undermines Joseph’s plan and restores comedic balance may satisfy some conventional sense of wanting a restoration of the “natural” order but it throws the film off balance.

Tragedy threatens and the momentary crossing of the boundary that separates comedy and tragedy in classical French theater may prove disconcerting to more than one spectator, especially since the resolution seems so hollow.

The director had worked with Chaplin on A Woman of Paris in which Menjou plays a similar role as a gentleman about town, his stock in trade as an actor in the silent era, and this film, even viewed in a dark print, is an effective exercise in style.

D’Abbadie d’Arast’s Hollywood career was apparently damaged by his reputation for being difficult and going over budget (reminding one of von Stroheim). He ended his career in 1933 with the direction of Topaze, which boasts fine performances by a cast headed by John Barrymore and Myrna Loy, closing his career with a film that played to his strengths as a director.

Mon 31 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

VIKRAM CHANDRA – Sacred Games. HarperCollins, hardcover; first edition, January 2007. Trade paperback: Harper Perennial; 1st printing, December 2007.

At 900 plus pages a good many readers may pass this one by, which is a pity, because it is a remarkable thriller that also manages to be an epic of Mumbai (Bombay) and through it, modern India at the birth of the 21st century. Written by Vikram Chanda, who divides his time between Harvard and Mumbai, it has the advantage of a writer comfortable and capable in English and at home in the streets of his homeland.

The hero of Sacred Games is Sartaj Singh, an Inspector with the Mumbai police, who is at war with Ganesh Gaitonde, the nation’s most wanted criminal and head of G Company, a sort of Indian Mafia with fingers in every pie. Their conflict will take the men across a wide spectrum of life in Mumbai.

A Sikh, known by his colleagues and the people of Mumbai’s streets as the ‘silky Sikh,’ Sartaj is divorced, over forty, and watching his career downspin, but he is determined to bring down Ganesh, who, despite his success as a criminal, is facing demons of his own, his very success isolating him from human contact.

As the novel develops, equal parts Eugene Sue’s Mysteries of Paris, The Godfather, police procedural, and Bollywood movie, Chandra reveals more and more of both Sartaj and Ganesh, while his portrait of the swirling exotic and poverty-stricken city evolves in the background.

“History has a shape …the universe has a design … For every insect, there is a predator. For every flower, there is a function. Some scientists still look at all this beauty, but insist it is result of natural selection, of chance and nothing else. They are blind. They are afraid. Pull back from the chance, look at it with the right vision, and chaos reveals its patterns.”

Finding those patterns is the way Sartaj will locate and find Ganesh, and by the time the two men confront each other, Chandra has given us a full portrait of life in Mumbai: its people, its poverty, its beauty, and its flaws. Sartaj and Ganesh themselves are fully revealed, and their inevitable conflict becomes a clash as epic as Ahab and the white whale.

The novel is a love letter to Mumbai, but one written with an eye to its realities. Structured like an old fashioned triple-decker, its scope is focused by the conflict of these two men, a battle worthy of Holmes and Moriarity, or Jean Valjean and Javert, but cast in the form of a thriller, although one of which it can be said, as it was of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, all life is in it. All the life of Mumbai anyway.

In Sartaj, we have a hero as complex as Maigret and as human, and in Ganesh an antagonist as complex and troubled as Michael Corleone, who finds the only man who can understand him or forgive him is the man sworn to destroy him. Like all great protagonist/antagonist pairs, the two men both compliment and contradict each other. Their battle is an epic one that sweeps in its wake all of the city they inhabit. Only one of the two can emerge from the battle: the one best equipped to grow within himself and face his own reality.

Sacred Games may not be for every reader, but if you ever want more from a thriller, good writing, ambitious narrative expertly controlled, and pure old fashioned storytelling, this is the book for you. That is also a first class thriller is a tribute to Chandra’s skills (and the extensive vocabulary of Indian words and slang at the end of the book).

As India’s role in the world grows more important we can look forward to getting a glimpse of Indian popular literature, and with this more serious book we will have some familiarity with the subject. In recent years Indian crime has figured as a background in John Irving’s Son of the Circus, and David Gregory Roberts Shantaram, both a far cry from the charm and gentle wit of H.R.F. Keating’s Inspector Ghote.

Read this one. It is a major work, and yet it reads like a thriller, a portrait of a world alien to most of us and at the same time utterly familiar and real. Despite its length and depth, you won’t want to put this one down. It is the kind of book you can move inside of and inhabit. And unlike most thrillers you won’t want this one to end.

But don’t get a hernia reading it. It is really a hefty tome, though surprisingly, one that doesn’t read that way. Epic and compelling aren’t always words you can use together, but both fit Vikram Chanda’s Sacred Games.

Mon 31 Aug 2009

RICHARD S. WHEELER – Flint’s Truth.

Forge, hardcover; 1st printing, May 1998. Paperback reprint: October 2000.

The first of itinerant newspaper printer Sam Flint’s adventures in the Old West was recorded in Flint’s Gift. This is the second; the third, forthcoming, is Flint’s Honor. And if this book is any measure, all three are worth tracking down and reading.

Moving from settlement to settlement with a printing press, several cases of movable type, newsprint and ink is not a task or career for the faint-hearted, nor is setting up shop in a town such as Oro Blanco, where the powers-that-be prefer that certain secrets stay hidden.

As Sam says on page 63: “You’d be amazed the amount of news that people don’t wish to see in print.” At stake is a fortune in land and gold.

This is a morality tale written in the guise of a western novel, with most of the characters taking stock parts. In fuller roles, though, besides Sam himself, are the philosophical Mexican priest who befriends him, and Libby, the skinny 13-year-old girl who becomes his right-hand aide. Each in their own way becomes a key to the tale, which is brutally honest and takes an ironic twist or two before a form of justice prevails.

Here’s a solid, picturesque glimpse into a unique time and place, one that rings a resonant chord of truth and right, and even better — as you can expect of all of Wheeler’s work — here’s a book that’s completely and compulsively readable.

— Reprinted from

Durn Tootin’ #2, July 2003 (slightly revised).

Mon 31 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

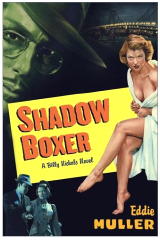

EDDIE MULLER – Shadow Boxer. Scribner, hardcover; 1st printing, January 2003.

There’s only one thing wrong with this throwback to the 1940s era of sports-based pulp fiction. Well, make it two. While Billy Nichols, who tells the story, is a crack San Francisco sportswriter nicknamed Mr. Boxing, there is not much in this book about either boxers or the fight game.

What it’s really about is the continuation of the murder case begun in Muller’s first novel, The Distance. It may be that the man Nichols brought to justice in the early book is not entirely guilty. The dead woman was the wife of boxer Hack Escalante — and not so incidentally, she was the also the one Nichols was having a secret affair with.

It’s a complicated tale, and if this is a new trend in detective fiction, it ought to stop right now. Without having read the first book, it’s impossible to know exactly who is who, and why or why not, and to whom. As detective fiction, it’s spinach, and I hate spinach.

As a writer of historical fiction, Muller has San Francisco and its seedy (and not-so-seedy) environs down cold. As a writer of hard-boiled pulp fiction, Muller certainly gives you your full money’s worth. Or even double, considering Nichols’ single paragraph longer-than-one-page rant on pages 152-153. Boiled down, it’s a long improvised version, with several choruses, of the old adage, “No good deed ever goes unpunished.”

This impromptu interjection is a work of noirish perfection, verging on Raymond Chandler territory, but the story that surrounds it is only better than average. What’s missing is an essential if not absolutely vital ingredient, a self-contained coherency. It’s too bad. It could have been a contender.

— May 2003

[UPDATE] 08-31-09. I’ve always meant to, but so far I haven’t done the obvious thing and start over by reading the two books about Billy Nichols in the right order. But I haven’t — in fact, I’ve yet to read the first one — and my review is based on the fact that Shadow Boxer is the only one I have.

Wondering, though, why this book never came out in paperback, and why there was never another book in the Billy Nichols series, I found out why on Eddie Muller’s website, in which he says, in part:

“I tried to do some things in this book that might be considered subversive for hardboiled crime fiction … Scribner [pulled] the plug on the Billy Nichols series before he even had a chance to get his legs under him. The publisher just didn’t get it, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Sun 30 Aug 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

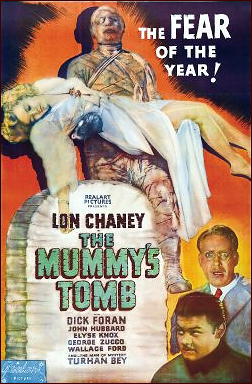

THE MUMMY’S TOMB. Universal, 1942. Lon Chaney Jr., Dick Foran, John Hubbard, Elyse Knox, George Zucco. Director: Harold Young.

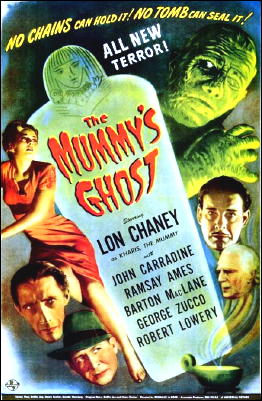

THE MUMMY’S GHOST.. Universal, 1944. Lon Chaney Jr., John Carradine, Robert Lowery, Ramsay Ames, Barton MacLane, George Zucco. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

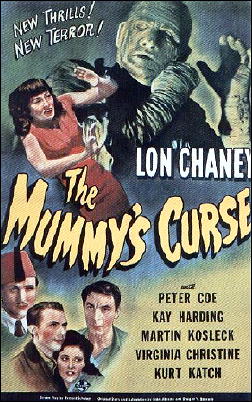

THE MUMMY’S CURSE.. Universal, 1944. Lon Chaney Jr., Peter Coe, Virginia Christine, Kay Harding, Dennis Moore. Director: Leslie Goodwins.

The Mummy (1932; reviewed by Steve way back here) is one of the great romantic films, and The Mummy’s Hand (1940) is a snappy little programmer, but the three Mummy films with Lon Chaney Jr. are the plodding, proletarian work-horses of the Monster Movie.

Slow-moving, badly-cast and sloppily-written, they have always struck me as examples of what a day-to-day Grind a Monster’s life must be. Kharis stumbles along playing out his curse with no joy, no sign of satisfaction, preying on the Old and Slow-Moving like he was stamping out Widgets on an assembly line, which is a very apt description of the way these films were produced.

Ben Pivar, the producer responsible for the series, was by some accounts a man of legendary Bad Taste, a filmmaker whose idea of Art was a story that could incorporate as much stock footage and as few sets as possible.

Indeed, his Mummy movies seem to be made up mostly of clips from earlier films, like youngsters devouring their parents.

Yet the Kharis films taken as a whole, convey a theme of surprising perversity: alone among Movie Monsters, Kharis fulfills his destiny. He destroys the defilers of Ananka’s tomb and twice reclaims his reincarnated Princess.

Yet, like the hero of a David Goodis novel, he never succeeds on his own terms. Each film ends with him joylessly sinking back into the grimy milieu from whence he came at the start, no wiser, no happier, and no longer loved.

Which is a pretty odd message to come from a low-brow producer like Pivar. Just a pity the films themselves are so damn boring.

Sat 29 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

A Review by ALLEN J. HUBIN:

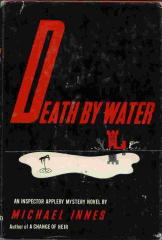

MICHAEL INNES – Death by Water.

Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1968. Paperback reprints include: Berkley, 1969; Perennial, 1991. UK title: Appleby at Allington: Victor Gollancz, hc, 1968.

Michael Innes, from whom I have come to expect great things, did not enchant me with a recent non-series mystery, Money from Holme. But Sir John Appleby returns in the present book, and the Innes magic is still operating.

Sir John seems to have retired to the country from Scotland Yard, and should be (as he recalls) “engaged in moving decently from bedtime to bedtime, from lunch to dinner.” One of these dinners is as a guest of Owain Allington, who has put some recently obtained wealth to the task of reacquiring the ancestral mansion.

The evening sees the discovery of the first of a series of bodies, all apparently accidentally deceased. Appleby, against his own inclinations and contrary to his own reasoning, finds himself drawn into the affair and smelling an unpleasant odor therein, and after a false start or two tracks the problem to its solution.

Death by Water is peopled with some wonderful comic characters, and others not so comic. Innes clearly enjoys playing with words, and fortunately his enjoyment is richly shared by the reader.

Do try Death by Water — it’s a pleasure.

– From The Armchair Detective, Vol. 1, No. 3, April 1968.

Sat 29 Aug 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

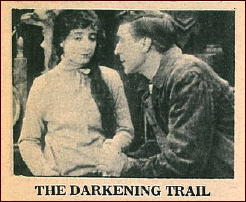

THE DARKENING TRAIL. Mutual Film Corp. 1915. William S. Hart, Enid Markey, George Fisher, Nona Thomas, Louise Glaum. William S. Hart, director; Thomas H. Ince, producer; written by C. Gardner Sullivan. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

William S. Hart, in his third feature film, plays Yukon Ed, hopelessly in love with Ruby McGraw (Enid Markey), owner of the local saloon, who has refused his offer of marriage dozens of times.

When Jack Sturgess (George Fisher), fleeing from his father’s wrath after he has wronged and abandoned a woman he refuses to marry, arrives in the small Alaskan town, Ruby, seeing in him the knight in shining armor she’s been waiting for, takes up with him.

Yukon Ed, willing to give the newcomer a chance, but ever watchful for any wrong done to Ruby, is there when Ruby, gravely ill, is waiting for the doctor who will never come because Jack, after promising to bring him, detours for a dalliance with a dancehall girl.

The intertitle “Requiem of the Rain” announces the grim conclusion and captures the dark poetry of this striking film.

Sat 29 Aug 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

LIONEL DAVIDSON – The Rose of Tibet. Victor Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1962; Penguin, UK, pb, 1964. Harper, US, hardcover, 1962. Reprint US paperback editions include: Avon, 1965; Perennial, 1982; St. Martin’s, 1996.

In a recent posting (The Spy Who Parodied, Part 3) I reviewed Agent 8 3/4 based on the novel Night of Wenceslas by Lionel Davidson.

Davidson, a British thriller writer, wrote only a handful of critically acclaimed novels, mostly in the spy story tradition. Among them were some of the best spy/adventure novels of the 20th century, and among those the outstanding work is The Rose of Tibet.

Davidson himself is a character in The Rose of Tibet, appearing in the framing sequence as he tries to put together the story of Charles Houston (pronounced ?Uston), a British journalist who traveled to remote Tibet at the time of the Chinese incursion there in the years after WW II. It is Houston’s story Davidson tells, and quite a story it proves to be.

It is difficult to discuss this book without mentioning other writers, Try to imagine James Hilton’s Lost Horizon written with the canny political eye of Eric Ambler, or H. Rider Haggard as re-imagined by Ian Fleming, perhaps a Harold Lamb novel written by Graham Greene (incidentally I mention Fleming and Greene with good reasons, both were admirers of Davidson and highly praised this book, as did Daphne du Maurier who asked in print if he was not the new Rider Haggard), John LeCarre in collaboration with Charles Crichton and T. E. B. Clarke, who penned many of the classic Ealing comedies.

The Rose of Tibet is all of that. It is a grand adventure, by turns very funny, very sexy, erotic, exotic, angry, honest , and above all compelling. Charles Houston, the most unlikely of heroes, proves to be the only hope of a remote Tibetan nation, one of those lost civilizations that writers like Hilton, Haggard, Burroughs, and others used to dot all over the wild places of the planet.

Davidson gives us a highly believable one, but no less enticing or exotic for that. The early scenes in this savage and exotic Eden, a sort of sensual paradise, are among the best such scenes you will encounter in fiction. It is strange yet familiar, exotic, erotic, yet completely believable. It is a splendidly evocative world.

Houston arrives in this remote, gentle, strangely savage, and doomed place on the eve of the Chinese invasion of Tibet, and as the PRC presses forward, a reluctant Houston finds himself chosen for the most delicate and dangerous mission of his life — to smuggle out a small boy and a young woman from this small Shangri La. The boy, a living god and the hope of the small nation, and the girl the repository of all that is erotic and beautiful, the rose of Tibet.

Their journey, accompanied by a small mountain pony, across the roof of the world one step ahead of the PRC, is the bulk of the book’s narrative. Treachery, his unworldly companions, the narrow roads and deadly mountain paths, murderous and unpredictable weather, a deadly encounter with an Asian brown bear, and the ultimate fate of Houston’s mission make up the rest of the novel, which ends with a delightful twist I won’t even begin to suggest after one of the most harrowing journeys in literature.

Literate and yet capable of spinning a tale with the best, Davidson’s works are a treasure trove for readers willing to delve into them. Night of Wenceslas, The Menorah Men (aka The Long Way to Shiloh) about a Raiders of the Ark kind of quest for the True Menorah.

And then there’s The Sun Chemist, Making Good Again, The Chelsea Murders, Kolymsky Heights, Smith’s Gazelle (a young adult novel), Under Plum Lake, and three more young adult novels as by David Line are among some of the best and most delightful books of the era.

Not a very great output for a period from about 1962 to 1998, but each and every one of them is a gem of great beauty.

Davidson deserves to be read, and almost certainly once you have read him you will reread him.

Among these gems The Rose of Tibet stands out. It is a perfect book of its kind, and I don’t really think you are likely to forget it once you have read it. Unlike many thrillers, it is one you will return to and enjoy time after time.

The Rose of Tibet belongs on that very small shelf of favorites that are equal in your heart as in your head, a curious mix of epic adventure, international intrigue, wild romance, Ealing comedy, and satiric commentary.

It is all that and more — little wonder Ian Fleming, Daphne Du Maurier, and Graham Greene fell under its powerful spell. I can honestly say that over the years everyone I have introduced the book to has ended up adding it to their list of favorite books of all time. It is certainly one of mine.

And don’t worry, I couldn’t possibly oversell it. It really is that good.

Sat 29 Aug 2009

T. T. FLYNN – Ride to Glory: A Western Quartet. Five Star, hardcover; 1st edition; 2000. Reprint paperback: Leisure, March 2004.

I’ll list the titles of the four novelettes and short novels it contains, and that’s all you’ll need to have a perfect picture of what this book’s all about: “Ghost Guns for Gold”, “Half Interest in Hell”, “The Gun Wolf” and “Ride to Glory.”

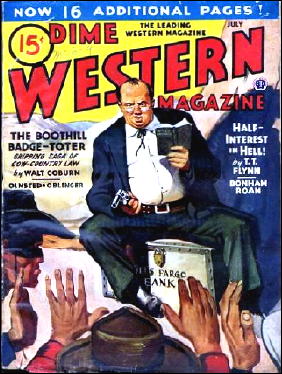

Action, that is, pure pistol-packing action. First appearing in the pages of old pulp fiction magazines such as Star Western (1935), Dime Western (1945 & 1949), and Western Story Magazine (1938), this marks the debut of these tales in hardcover.

And whenever there’s room to breathe between the rounds of gunfire, there’s always a chance that romance will work its way into the story, one way or another. According to the creed of the day, or so it’s implied — if not outright stated — it’s the love of good women that gives men the courage to risk their necks against the crooked ranchers, conniving Mexican despots, and other assorted outlaws found inhabiting these pages, and by extension, the entire American west.

If these stories succeed, it’s by sheer story-telling power, not by the grace or elegance of the writing. While T. T. Flynn was the contemporary of such western writers such as Max Brand and Zane Grey, it’s plain to see that he simply wasn’t in their league, at least not in terms of word-slinging ability.

But if you can sit back, turn off your critical eye, and allow these yarns of yesteryear to simply take over, what you’ll be in for is four installments of the ride of your life — and I ask you: What could be better than that?

— Reprinted from Durn Tootin’ #2, July 2003 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 08-29-09. I’ve recently had to drop out of a western fiction apa called Owlhoots — a pure lack of time — but in the ten or so issues I did for it, there are some articles and reviews I did that I’ll gradually be reprinting here on the Mystery*File blog.

I regret to say that at the moment, I don’t have access to the book itself, and I seem to have made no record of it at the time. Right now, except for one story, I can’t tell you which one came from which magazine. When I come across the rest of the information, I’ll add it later:

Half-Interest in Hell, Dime Western Magazine, July 1945.

[UPDATE #2] Later the same day. Walker Martin has come to my rescue. See comment #1.

Fri 28 Aug 2009

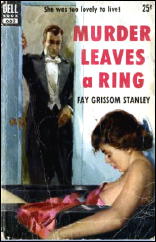

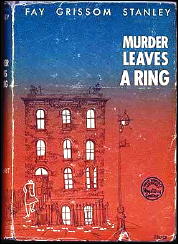

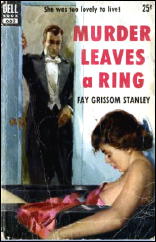

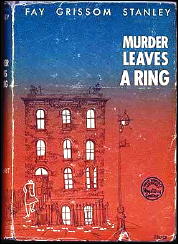

FAY GRISSOM STANLEY – Murder Leaves a Ring.

Dell 662; paperback reprint; no date stated, but circa 1953. Cover art: James Meese. Hardcover edition: Rinehart & Co., 1950. Hardcover reprint: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, 4-in-1 edition, January 1951.

It’s difficult to make out from the image I found, but if I’m reading what’s in the small circle on the cover of the hardcover edition correctly, this book was the winner of a “Mary Roberts Rinehart Mystery Contest.”

It was also one of only two mystery novels Fay Grissom Stanley, 1925-1990, wrote. The other was a paperback original from Popular Library in 1975, a gothic romance titled Portrait in Jigsaw, as by Fay Grissom.

There is a short online autobiographical sketch by her daughter, Diane Stanley, an illustrator and author herself, in which she talks about her mother (follow the link), and mentions other books she wrote. Her mother was taken ill by tuberculosis for several years, which may explain the long gap between the two books, and perhaps why there were only two.

Murder Leaves a Ring is pure detective fiction, and the cover (as you will have seen for yourself) falls into the “body in a bathtub” subgenre. It’s told by the primary protagonist, Katheryn Chapin, a would-be mystery writer herself, as we learn on page one: she’s working on the manuscript of a novel called “Murder on Monday,” just before climbing into a tub, where she first must clean the ring left behind by one of her two roommates, a showgirl named Iris McIvers.

Later on, during a party of fellow Manhattanites, many in the world of the theater, it is Iris’s body who’s found in the very same tub, fully clothed, but with a stocking knotted tightly around her neck. It is learned soon after that Iris had been doing a brisk business of shakedown if not out-and-out blackmail – among other secrets that Katy and Bonnie, the other roommate, had not known about her.

One of Iris’s recent meaner tricks was that of stealing Katy’s fiancé from her, a writer of plays named Mark, and it is her that Katy tries to protect when questioned by the police in the form of Captain Steele, who castigates her quite vigorously on pages 76-77 for both her lack of observation (significant, he suggests, for someone who hopes to write mysteries) and/or her lack of cooperation (for which at least the reader knows the reason).

There is a long laundry list of suspects in Murder Leaves a Ring – all to the good! – all with varying degrees of conflicting interests, a map of the three girls’ apartment even before page one – and it’s needed! – and an elaborate trap for a suspected killer toward the end. And if I were to mention several twists in the tale along the way, I hope you will forget that I said that, as the pleasure’s in the reading, and not in the reading about it.

The opening chapters do not flow as well as they should – it was not surprising, after the fact, to learn that this was the author’s first book – but as the story picks up some momentum, so does Miss Chapin’s narrative, which becomes noticeably smoother and easier as her encounters with the police and the killer grow more and more serious.

Captain Steele is something of a conundrum, married to his job and seemingly hard-boiled through and through, but by the end he seems to have thawed out considerably, even to the extent of becoming perceptibly human.

If he and Miss Chapin had ever been in a second mystery novel together – and there is a hint of something in the air at the end, and perhaps with young Dr. Harrison, too – I’d snatch it up in an instant.

Next Page »