September 2009

Monthly Archive

Wed 30 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

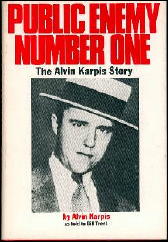

ALVIN KARPIS & BILL TRENT – Public Enemy Number One. McClelland & Stewart, Canada, hardcover, 1971; Coward McCann & Geoghegan, US, hc, 1971, as The Alvin Karpis Story. Paperback reprint: Berkley, 1972.

While authors like Raymond Chandler were practicing violent crime in the pulps, other folks were doing it in real life, as witness this book by Alvin Karpis and Bill Trent. For those who may not remember, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis was one of the most notorious of the rural bank robbers roaming the mid-west from 1931 to 1935,and in a roster that induded John Dillinger, Bonnie & Clyde, Baby Face Nelson and Pretty Boy Floyd, “Creepy” Karpis was, one of the sharpest and most successful.

He was also the only one to survive and write (or ghost-write) his memoirs, and I have to say he and Bill Trent make a good job of it. Karpis/Trent can detail a bank robbery and car chase with the staccato skill of Richard Stark or Dan J. Marlowe, and he avoids any tendency to glamorize or mitigate his crime; in this narrative, he’s just a professional thief, doing what he does well.

Karpis also avoids writing anything that might jump up and bite him in the ass. He and his gang were responsible for a goodly number of deliberate murders and incidental killings, but Karpis doesn’t talk about any of them. When he does go into detail about a killing, he usually ascribes it to someone else (usually “Doc” Barker) though Karpis seems to remember a whole lot of incidental details for a guy who wasn’t there at the time.

Just as much fun as the gory details, though, is Karpis’ gently cynical view of life, crime and law enforcement.

He makes no excuses for himself, and builds no illusions about his co-workers. Bonnie and Clyde he describes as being mentally sub-normal, and though “Ma” Barker was generally depicted in those days as a criminal mastermind who spawned and directed a gang of killers, according to Karpis, “She couldn’t organize breakfast. She knew where we were getting the money, she knew what we did, but whenever we sat down to plan a job, we sent her out to the movies.”

I also got a kick out of Karpis’ description of his arrest by J. Edgar Hoover — the only major collar Hoover ever made personally, and according to Karpis, something of a comic opera. Public Enemy is less critical of Hoover than later books would be, but somehow the bankrobber’s casual dismissal of him as a political hack is even more damning than some of the full-blown indictments that followed. It’s as if a real man of action just had no time for a power-hungry poseur like Hoover.

Wed 30 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

JAMES ELLROY – Blood’s a Rover. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, September 2009.

James Ellroy has long been the mad bad devil dog of crime fiction, and beginning with American Tabloid then The Cold Six Thousand, the first two books of the “Underworld USA” trilogy, he made a political move toward a sort of crackpot history of all the paranoid secret conspiracy theories of the twentieth century from the days of Bugsey Siegel in Vegas to the Kennedy election and assassination on.

In his latest novel, Blood’s a Rover (the title is from a poem by A.E. Houseman) he has settled on perhaps the most tumultuous period in American history since the Civil War, the period from the assassination of Martin Luther King to the death of J. Edgar Hoover on the eve of Watergate, 1968 to 1972.

This isn’t to suggest Ellroy has forgotten his roots in the mystery and crime genre. The book opens with a splendidly choreographed armored car robbery in a black neighborhood in Los Angeles. It is a perfectly done scene that deserves to be filmed.

Blood’s a Rover turns on three characters and their relation to a fourth, a beautiful and legendary radical American woman, Joan Rosen Klein, aka Red Joan. The three men are Dwight Holly, J. Edgar Hoover’s personal gunman, who knows all the secrets of his secret-ridden boss and some of his own, and who may be damned by his growing humanity, thanks to his growing love for one of his informants; Wayne Tedrow, who murdered his own father, who had been part of Hoover’s operation Black Rabbit to disgrace and finally kill Martin Luther King, and who now finds as he moves to building a casino empire in the Dominican Republic that his politics are growing more radical; and Don “Crutch” Crutchfield, a young LA private eye, once Joan’s lover, and on the cutting edge of the right wing reactionaries and the left wing crazies who populate the story.

These three will be thrown into a dizzying world of violence and conspiracy tying together a brutal and bloody armored car robbery; Hoover’s plans for Operation Baaad Brother aimed at creating then cracking down on black radicals; the 1968 Presidential election, and the Chicago riots at the Democratic Convention; Sal Mineo, the Oscar-nominated actor fallen to the level of gay street hustler and informer; two psychotic LA cops, one white and one black; and Howard Hughes’ Mormon aide, a closeted homosexual — among others.

Wayne blundered into the hit plot in post-hit free fall. He linked Jack Ruby to Moore and that right wing merc Pete B. He saw Ruby clip Lee Harvey Oswald on live TV.

He knew. He did not know his father knew. It all went blooey that Sunday.

JFK was dead. Oswald was dead. He tracked down Wendell Durfee and told him to run. Maynard Moore interceded. Wayne killed Moore and let Durfee go. Pete B. interceded and let Wayne live.

Pete considered his own act of mercy prudent and Wayne’s rash. Pete warned Wayne that Wendell Durfee might show up again.

This goes on for two pages, explaining what occurred before in American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand, a crackpot history of American conspiracy that has ended with Hoover engineering the assassination of Martin Luther King, an event that will eventually be his downfall through Dwight Holly, Wayne, and Crutch. I’d quote more, but it isn’t easy to find a good sustained quote that doesn’t end in an obscenity or two

As Nixon nears the White House, the plots spin together in a melange of conspiracy and insanity that only ends when Crutch destroys Hoover’s secret files in an act of vandalism that triggers the FBI director’s fatal stroke.

It’s difficult to describe the book. It is written in a style that is part jazz riff and part docu-noir, and spins from one act of stunning violence to another. The plot spins in and out of control from racial politics in the LA police to Hoover’s paranoia, to the growing radicalism of the protagonists as they rebel against the world they live and operate in, much of it inspired by Red Joan who eludes Hoover and the police while planting her seeds of discontent.

Each of the three main protagonists is saved or destroyed by his own growing soul and conscience, and the book carries the story from the first two books to its logical end with the death of Hoover.

Whether or not Ellroy believes this insane plot or not is impossible to tell. The book at times seems to have been bred out of Richard Condon by way of William Burroughs and The Turner Diaries. It all makes a sort of sense if you don’t stop too long to think about it, and certainly it is a brilliant work, though at times the confluence of plots, conspiracy, violence, and secret history threatens to teeter over into something closer to the Marx Brothers than the dark secret history of our recent past Ellroy intended. His ambition has almost, if not quite, exceeded his grasp and ours.

Blood’s A Rover is the weakest of the three books in the trilogy, perhaps naturally since it is the repository for tying up all the loose ends. At times it feels as if you should have American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand open beside you as you read in order to keep up. Even then I don’t know if that would be possible.

But Ellroy has developed a style and voice that are unique. No one else writes like him, and no one else finds that strange mix of humor, horror, paranoia, humanity, and violence that mark his works. It is the work of a master, about the price we pay to “live history,” but it is a masterwork that dares to dance dangerously close to the edge, and by staying true to his vision, its creator risks losing some readers to its purity of vision.

There are times you may not know whether to laugh or cry, and times I’m not sure Ellroy knows whether he wants you to do one or perhaps both.

This completes the “Underworld USA” trilogy, and ties it up, though I can’t say neatly. It is likely to stand a while as a unique achievement, but it is not without flaws, not without questions unanswered, but the trip is worth taking, even if untangling the conspiratorial plot may require a bottle of aspirin, and more than one reading.

Blood’s A Rover is the work of a great writer stretching himself, but it is not a perfect work. Its flaws should not keep you away from the book, but anyone reading it should be warned. Ellroy’s world is unforgettable, but at times incomprehensible as well.

Luckily his prose carries you past the rough patches, but when you turn the final page you may not be sure how you feel about the trip. At this point I suspect the final judgment of the critics will be to find this a flawed masterpiece by one of our most interesting writers, but I can’t say I would be too surprised if their judgement was simply, “huh?” It’s that kind of book.

Tue 29 Sep 2009

STATE OF PLAY. BBC-TV, 2003. [6 x 60m miniseries] John Simm, David Morrissey, Kelly Macdonald, Bill Nighy, Amelia Bullmore, Benedict Wong, Rebekah Staton, Philip Glenister, Polly Walker, James McAvoy, Marc Warren. Screenwriter: Paul Abbott; director: David Yates.

First of all, do not confuse this with the film produced in the US in 2009 starring Russell Crowe, Ben Affleck, Rachel McAdams, Helen Mirren and Robin Wright Penn.

No matter how good this latter group of actors may be, and no matter how many names you recognize in the US production over that of the BBC series, when it comes down to sheer entertainment value, I doubt that there’ll be much comparison. In the overall scheme of life and a list of things that are possible, this doesn’t seem to be one of them.

But I say that without having seen the US version. On the other hand, it’s just been released on DVD, so I’m sure I’ll give it a try. If and when I do, I’ll report back later.

Having spent all of last week – eight hours’ worth — watching the BBC version and being completely enthralled, I don’t see how reducing the running time down to two hours can possibly improve either the story or the characterizations. (The eight hours includes watching each of the first and last hours twice, the second time in each case with running commentary.)

Much of the miniseries takes place in the newsroom of a busy London newspaper, and although I’ve not been in a newsroom recently — not since I gave up my job reviewing mysteries for the Hartford Courant — it looked and felt to me as authentic as actually being there: a huge room bustling with people working and moving around with individual reporters’ desks with stacks of papers and files and anything else that a reporter might want his or her hands on at a moment’s notice.

It was difficult, in fact, to come down from the giddy feeling produced by the top-notch overall atmosphere, the competitive camaraderie, the highs of stories when they’re panning out followed by the lows when they’re not, especially when the latter are caused by management buckling under pressure from those up above concerned with the bottom line, or even worse, from the government in the form of the police or some agency involved with rules and regulations regarding, perhaps, the oil industry.

Dead in a railway accident is Sonia Baker, a research assistant to Stephen Collins (David Morrissey), a up-and-coming Member of Parliament who’s chairing The Energy Select Committee.

When he falls apart in tears at an ensuing press conference, his secret’s out. Although married with two young children, he’d been having an affair with the dead girl.

Was it an accident, or was it suicide? Of course we (the viewer) know better than that.

On the story from the beginning is the suitably scruffy Cal McCaffrey (John Simm), with a little more inside information than any other reporter since he’s a friend of Collins and at one time his campaign manager.

Complicating matters considerable is the affair that McCaffrey ends up in with Collins’ wife (Polly Walker). This adds an edge to an ever-widening story that points more and more to a grand conspiracy going on, but the facts could not be more elusive, always seemingly just out of reach.

Every once in a while the British accents made some of the dialogue undecipherable but not once did I find the problem unmanageable. Surprising enough, I found the broad Scottish accent of reporter Della Smith (Kelly Macdonald) more understandable that some of the British ones, once my ear became more and more accustomed to it.

All of the players are marvelous, pitch perfect (other than accents) in every way, including (and especially) Bill Nighy as Cameron Foster, the managing editor. He’s urbane, witty, snippy, dedicated and slightly acerbic in each and every situation where he needs to be each of the above.

One flaw, if there is one, may also be a large one. The ending, while a totally natural one in one sense, also seems grafted on (or retrofitted, if you will), and it takes some effort to reconcile it some of the earlier threads of the plot — and there are a lot of them!

Forgiving that is easily done, however, given the overall high quality of the presentation, and how delightfully and completely enjoyable the entire production is.

Tue 29 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bruce Taylor:

GEOFFREY HOUSEHOLD – Watcher in the Shadows. Little Brown, US, hardcover, 1960. Paperback reprint: Bantam, 1961. UK edition: Michael Joseph, hc, 1960. TV movie: CBS, 1972, as Deadly Harvest.

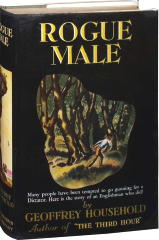

While not as famous as Rogue Male, this too is a first-class example of that uniquely British crime novel, the thriller.

Working quietly in a sleepy English village, Charles Dennim, a zoologist, watches as the front of his home is blown apart by a letter bomb. Investigation proves the bomb was meant for him. But why? Is it because of some event in his past? Perhaps his wartime service undercover behind German lines?

Information from a well-placed government friend convinces Dennim he is being stalked by a faceless killer who has struck at least three times before and always with impunity. Unwilling to risk the lives of those close to him, Dennim takes to the open fields of the English midlands and sets himself up as a Judas goat while trying to lure his would-be executioner into the open.

The hunter becomes the hunted as a ruthless murderer bent on revenge stalks his prey. The final confrontation — at night in an abandoned barn on a lonely rise — will leave the reader breathless.

This is a fine novel in all respects, with a powerful and moving climax.

Recommended among Household’s other thrillers are Arabesque (1948), A Rough Shoot (1951), and especially Dance of the Dwarfs (1968), which is in the same hunt-and-chase mold as Rogue Male and Watcher in the Shadows.

Household is also an accomplished writer of short stories of adventure and suspense, some of the best of which can be found in such collections as The Salvation of Pisco Gabar (1940), The Brides of Solomon (1958), and Sabres on the Sand (1966).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 29 Sep 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

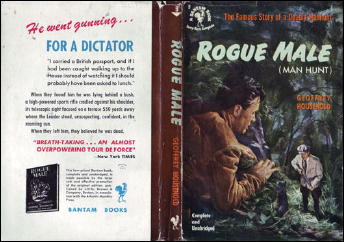

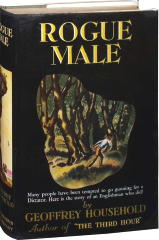

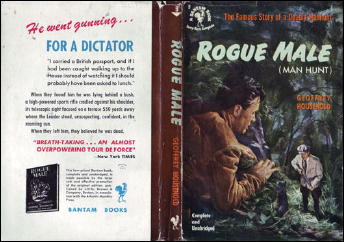

GEOFFREY HOUSEHOLD – Rogue Male. Little Brown, hardcover, 1939. UK edition: Chatto & Windus, hc, 1939. Also published as Man Hunt: Triangle, US, hc, 1943. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including Bantam #9, 1946, w/dust jacket (shown); Pyramid R930, 1963.

Film: TCF, 1942, as Man Hunt (with Walter Pidgeon, George Sanders, Joan Bennett; reviewed here by David L. Vineyard.

Rogue Male caused quite a stir in both England and the United States when it was first published. It is the story of one man’s private war with Hitler and the Gestapo, although neither is mentioned by name.

But it is much more than that, else its popularity would not have survived the war years: It has been almost constantly in print over the past five decades. The Saturday Review of Literature said, “You are not likely to find a better adventure story.” And the New York Times called it “an overpowering tour de force … spare, tense, desperately alive.” Those superlatives still apply today.

The novel is told in the form of a first-person journal whose author is never identified. We know only that he is a famous and well-to-do British sportsman whose name is widely known and who has been “frequently and unavoidably dishonored by the banners and praises of the penny press.”

In the days before full-scale war in Europe, this man set out alone on a hunting trip in Poland, and it occurred to him there that it might be his greatest challenge to stalk a different kind of game for a change — human game.

Not to kill, of course; he is not a psychopath. He wants only to get close enough to a certain heavily guarded dictator to place the man in the cross hairs of his rifle’s telescopic sight.

And this he does, being a superb and wily outdoorsman: He comes within a finger pressure of ridding Europe of its greatest tyrant. But he doesn’t fire; and because he doesn’t, he is caught and brutally tortured.

He tells his captors the truth, but they don’t believe him. And even if they do, it doesn’t matter; he must be killed to prevent the truth from leaking out and others trying the same thing.

They put him over a cliff to make his death took like an accident. Only he doesn’t die; he survives the fall. And even though he is more animal than man at first, unable to use his hands (they have been mangled by his tormentors) and with his left eye a bloody horror, he still manages to make his arduous way to a seaport and stowaway on board a ship bound for England.

Once he arrives, however, his ordeal hasn’t ended; it has only just begun.

He knows that agents of the tyrant will be sent after him, knows that his only hope of survival is to disappear completely and without a trace. He makes financial arrangements with the solicitor in charge of his estate, then leaves London.

But at the Aldwych train station he is accosted by an enemy agent and has no choice but to kill the man. As a result, he becomes a fugitive from the British police as well. He flees to a remote part of Dorset, covering his tracks as he travels, and quite literally goes to ground: He digs out an undetectable burrow inside an isolated hedgerow.

You might think he is safe then; so did he. But he isn’t. He makes one mistake that leads the enemy agents and the police to his vicinity and forces him to live like a mole inside his burrow for days on end. And when he emerges, it is to kill again, and to vow to return to the tyrant’s country and once more put the man in the cross hairs of his rifle, and this time to pull the trigger.

This is a nightmarish novel, filled with breathless chases, fascinating detail-work, and images that will haunt you for days after reading. If you like chase/adventure stories and you haven’t yet read Rogue Male, do yourself a favor. You won’t be disappointed.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 28 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

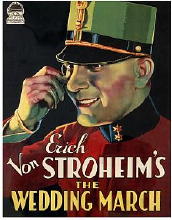

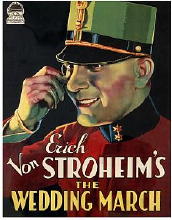

THE WEDDING MARCH. Paramount; 1928. George Fawcett, Maude George, Erich von Stroheim, George Nichols, ZaSu Pitts, Fay Wray. Erich von Stroheim, director; screenplay by von Stroheim and Harry Carr. Photography by Hal Mohr, Buster Sorensen, and Ben Reynolds; art direction by Richard Day and von Stroheim. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

After the cost overruns of The Wedding March and withdrawal of funding before von Stroheim was able to complete Part II as he had planned it, he essentially ended his directing career with Queen Kelly (1929, also incomplete). But what a tribute to his extraordinary skill the first part of The Wedding March is!

Von Stroheim was, of course, popularly known as The Man You Love to Hate, but his role as Prince Nicki von Wildeliebe-Rauffenburg is almost sympathetic. He’s expected to marry properly (that is, a rich wife) but he falls in love with crippled musician Mitzi Schrammell (Fay Wray), much to his (and her) parents’ dismay.

He woos the besmitten Mitzi in a flowered bower where she finally succumbs to his charms, then summarily abandons her when he goes along with his parents’ ambitions (to replenish the family coffers, constantly depleted by the family’s spendthrift ways) and, at the film’s climax, marries Cecelia Schweisser (ZaSu Pitts), the daughter of a wealthy merchant.

The magic of the film (aside from the fine performances) is in von Stroheim’s detailed portrait of an ancient aristocracy largely going to lavish seed, hedonistic and opportunistic, interested only in perpetuating its indolent way of life.

Prince Nicki seems to show some promise of breaking with his class, but if he is to marry a commoner, she must pay for the privilege of marrying him.

Nicki and Mitzi first meet at an elaborate outdoor ceremony where the equestrian Prince is parading with his company in a reel that’s filmed in beautiful two-strip color. If only the quality of the print were as good for the black-and-white sequences that make up most of the cinematography. By the last reel, the print is almost unwatchable, washed out, grainy, with the intertitles unreadable.

One of the Cinevent attendees I was talking to blamed the poor quality on the fact that the print screened was 16mm. My friend Charlie Shibuk has seen a good print of the film and told me that William Everson found his 16mm print to be of quite acceptable quality. It would seem that better prints are available, and I wonder if anyone screened this print before scheduling it.

In addition, the writer of the program notes claims that although von Stroheim began to film part II, the film was taken away from him and given to Josef von Sternberg, who put together a poor version. He further claims that Henri Langlois, of the French Cinematheque, allowed his print to deteriorate.

Charlie has told me that the writer was wrong on both counts. Von Stroheim did, in fact, edit a version of Part II (at the end of which Nicki tries to atone for his rejection of Mitzi), and the French print was destroyed in a fire. So it would seem that the von Stroheim legend endures, a mixture of fanciful fiction and fact.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. For a three-minute glimpse of the wedding march itself — in color — see this YouTube clip.

Mon 28 Sep 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

MAN HUNT. 20th Century-Fox, 1941. Walter Pidgeon, Joan Bennett, George Sanders, Roddy McDowall, John Carradine. Screenplay: Dudley Nichols, based on the novel Rogue Male by Geoffrey Household. Director: Fritz Lang.

Few books catch the public imagination the way Geoffrey Household’s classic novel of chase and pursuit Rogue Male did. It was a best-selling phenomenom and became one of the classic thrillers of all time, near the top of everyone’s list of the best thrillers ever written.

It was natural it would come to film, and luckily for all concerned, it did so at the hands of one of the greatest directors in film history, Fritz Lang.

Fritz Lang was a legendary German director who fled Nazi Germany by the skin of his teeth, so Rogue Male was a natural project for him — how could he resist the tale of a big game hunter who decides on a lark to stalk the most dangerous game of all — Adolf Hitler.

It should be noted Rogue Male was written before the war broke out in September 1939, so Household never specifically says in the novel that his hero is stalking Adolf Hitler, merely an unnamed European dictator.

As if the public couldn’t figure it out.

Especially at novel’s end, when the hero vows to finish the job.

When the war did break out, at least one British general, who himself was a big game hunter, had to be talked out of trying to duplicate Household’s novel in the real world.

Bringing the book to the screen was no easy task. The novel, written in the first person, is a curiously compelling and believable work. It reads like the actual memoir of the narrator and builds incredible suspense.

Finding the right actor to play the lead was vital. It needed someone stalwart and serious yet human and likable — after all, the United States was not in the war, and this was a film about assassinating the leader of another country. Warner Brothers may have fired the opening salvo with Confessions of a Nazi Spy, but not all Americans were convinced the war was any of our business. Pearl Harbor would soon change that, but not yet.

Which is why Walter Pidgeon was the ideal choice to play the lead, that sane, strong, yet gently humorous Canadian actor who in Mrs. Miniver would shortly become the very icon of calm British courage in the face of incredible odds. The simple fact that Pidgeon was the man behind the telescopic sites let the viewer know that he was not only the hero, but he was justified in his actions.

The existence of actors like Pidgeon was one of the strengths of the old studio star system. His very presence told the audience as much as any dialogue could reveal.

The film opens with Pidgeon in what is obviously Germany, near what is obviously Hitler’s Bavarian escape Berchtesgarten. Pidgeon, a famous British hunter, is hunting stags when he realizes where he is, and for reasons he can’t explain decides to see if he could get a clear shot at the dictator. Not that he would ever pull the trigger …

But when he is caught it isn’t so easy to explain. The Germans, particularly George Sanders, are sure he is a British agent, and even if he isn’t, the provocation of a Brit caught trying to kill the Fuehrer is to good to pass up. They beat and torture him, and then plan to dump his body, but he outwits them and escapes.

Now the manhunt is on. Pidgeon is hidden on a boat traveling to England and aided by a cabin boy (Roddy McDowall who teamed with Pidgeon in John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley).

He arrives in England only to find there is no where to turn and no one to help him. He can’t go to the police and he soon finds Sanders and his men in England are on his trail.

He’s trapped in a nightmare and can’t wake up. His brother wants nothing to do with him, the government would just as soon he go away, the police would as soon arrest him, and he is actively being hunted by enemy agents in his own country.

After a narrow escape in the London underground with sinister John Carradine, Pidgeon knows his only hope is to go to ground in the wild, where he has a chance based on his survival skills. It’s a splendidly shot sequence that reminds of Lang’s brilliant use of shadow and light in his silent work.

But he needs help, and that comes in the form of Joan Bennett, a prostitute he has picked up in escaping the German agents. (Production code or not the movie is pretty obvious what Bennett’s profession is.) Though she is clearly from another class he is charmed by her, and she by his gentlemanly ways. She agrees to help him, and he in return arranges to help her escape her life.

He arranges with his solicitor, one of the few friends he can rely on, to help her while he is in hiding. In the novel the solicitor is Jewish, in the film that’s never exactly said, though perhaps subtly implied.

The scenes between Pidgeon and Bennett are touching and human. When he leaves her he gives her a little token, A pin, a metal arrow, to remember him by.

As you might guess, that pin is going to be important.

Meanwhile after a tearful goodbye in the fog on Tower bridge (and an infamous mistake that puts Parliament on the wrong side of the Thames), Pidgeon heads for the country and finds a small cave he converts into a hideout sets out to keep a low profile.

But Sanders is hot on his trail and tracks him down. Now Pidgeon is pinned in his little hideout with Sanders outside promising to let him live if he will just sign a confession he intended to kill Hitler. And to break Pidgeon’s will he produces proof there is no hope.

The arrow pin Sanders took from Bennett when he tortured and killed her to find out where Pidgeon was hiding.

But Pidgeon didn’t go to ground because it would make him defenseless. He may be trapped but he still has his mind. Using a board from his bed, some rope, his belt, a stick and the arrow pin, Pidgeon builds a makeshift crossbow.

If he can only lure Sanders to the small opening by pretending to sign the confession — before Sanders kills him.

The film ends with Pidgeon enlisted after the war starts in the RAF. But on a mission over Germany he produces his hunting rifle and parachutes from the plane. This time he will hunt the beast from rooftops, not forests, and this time we are assured, he won’t miss.

The novel ends somewhat differently in that we learn that the narrator unconsciously intended to kill the dictator all along. His lover was killed in the Spanish Civil War, but as in the film the book ends as he returns to Germany determined this time to finish the job he began.

It’s hard to gauge just how comforting that thought was to millions of Brits and Americans, the idea that somewhere in Germany one lone man with a gun was stalking the biggest monster of them all. The book was an international sensation and many actually believed a British big game hunter was loose in Europe stalking the German dictator. It was no longer a novel or a film, it had become an urban legend.

Rogue Male was remade under its original title by Clive Donner with Peter O’Toole as the hunter and Sir John Standing in the Sanders role. It was an excellent film, somewhat closer to the novel than the Lang version and featuring one of the last performances of Alistair Sim.

Geoffrey Household went on to write many classic novels of chase and pursuit including Watcher In the Shadows, The Courtesy of Death, Dance of the Dwarfs, and not long before his death the long awaited sequel to Rogue Male, Rogue Justice, which for the first time reveals the characters name and follows his mission in Nazi Germany and his final fate in post war Africa. It is one of the few sequels worthy of the original.

But nothing could recreate the impact of Rogue Male or the Fritz Lang film version, Man Hunt. At a time when the world seemed to have gone mad and the forces of darkness threatened to overwhelm the forces of decency and hope, the idea that somewhere one sane man opposed the darkness, alone and with a gun from the shadows and rooftops, filled a need for hope and a spirit of resistance.

Postwar study of German secret correspondence even revealed they took it seriously, thinking Household’s novel was based on an actual person. Many a rooftop was scanned looking for Household’s fictional hunter.

Man Hunt is a fine film, one of Lang’s best American films, and features a strong screenplay by John Ford favorite, Dudley Nichols. The cast is first rate, with Pidgeon, Sanders, and Bennett all outstanding in their roles. Roddy McDowall is touching in a small but key role, and John Carradine is at his sinister best.

I defy you not feel like cheering even today as Pidgeon descends through the clouds, and we are told this time he won’t miss. It is old Hollywood at its best.

And time has given both film and book a deeper meaning. Today in the light of Lee Harvey Oswald and others, both have an ambiguity never intended at the time. Reading Rogue Male or viewing Man Hunt today might best be accompanied by Frederick Forsyth’s Day of the Jackal and the Fred Zinneman film of that book.

Still, in 1941 when Man Hunt hit the big screen, there was no ambiguity. We knew right and wrong then and we knew what was needed. It was a darker and simpler time and one man with a gun could matter — or at least it seemed that way, and as symbols of hope went, it proved a remarkably resilient and powerful one.

Mon 28 Sep 2009

DOROTHY CANNELL – The Importance of Being Ernestine.

Penguin, paperback reprint; 1st printing, April 2003. Hardcover edition: Viking Penguin, 2002.

As in most things in life, timing is everything, but especially when it comes to comedy. And when it comes to comic detective novels, it’s difficult to explain in words what works and what does not, and when (and why) the beat is off.

This is the 11th in Dorothy Cannell’s series of books about amateur detective Ellie Haskell, and it’s one of the funniest mysteries I’ve happened to read since the Inspector Dover books. Note to myself: It’s time to read Joyce Porter again, to see if Dover is as humorous as I remember, or if he was really only a rather obnoxious dolt. There’s a fine line, you see.

Ellie, married, with three young children, is an interior decorator by trade, but — miffed at her husband, she takes up crime-solving with her housekeeper Mrs. Malloy, who’s been moonlighting as an would-be assistant to a private eye. Named Jugg. Nicknamed “Milk.” Of course.

Here’s Mrs. Malloy explaining to Mrs. H. what her latest ambition in life is, before their first client arrives (page 15):

“I’d had this lovely fantasy, you see, of Mr. Jugg finishing with his difficult client, then laying eyes on me. I’d be emptying the ashtrays, and his eyes would be drawn like a magnet to me Purple Passion lips and it would hit him like a wallop that I was a real woman.”

“Whereupon he’d ask you to marry him?”

“No,” she spoke dreamily, “he’d tell me in ever such a masterful voice to sit down and take dictation.” A pause. “What could be sexier than that, Mrs. H.?”

I didn’t answer.

The pause is a stroke of genius. It’s all in the timing, as I say. The client then comes in, and the case is on. An elderly lady who (she now believes) wrongfully fired a maid who was pregnant (possibly by the lady’s now deceased husband) and accused of stealing a valuable brooch now wants to find the child and make amends. To complicate matters, a number of Mrs. Krumley’s aged relatives have started to die off in highly unusual (and suspicious) circumstances.

Taking over the case in Mr. Jugg’s absence, Ellie and Mrs. Malloy find no dark streets to go down. Most of the suspects live in or around the Krumley mansion, Moultty Towers (pronounced Moldy), and are for the most part, members of the upper strata of society.

There are lots of red herrings and false trails and strange and stranger events that subsequently occur, and it comes as no great surprise that a huge muddle is made in wrapping everything up, presenting the reader with one awkward discombobulated package at the end. I read the last chapter a couple of times, and I confess, it all makes sense. Sort of.

Would I read another? Absolutely. Weak ending or not, there’s a definite charm that’s present here, and I think it’s unique. Nothing similar comes readily to mind.

— May 2003

Bibliographic data

The Ellie Haskell series —

1. The Thin Woman (1984)

2. Down the Garden Path (1985)

3. The Widow’s Club (1988)

4. Mum’s the Word (1990)

5. Femmes Fatal (1992)

6. How to Murder Your Mother-In-Law (1994)

7. How to Murder the Man of Your Dreams (1995)

8. The Spring Cleaning Murders (1998)

9. The Trouble with Harriet (1999)

10. Bridesmaids Revisited (2000)

11. The Importance of Being Ernestine (2002)

12. Withering Heights (2007)

13. Goodbye, Ms. Chips (2008)

14. She Shoots to Conquer (2009)

Sun 27 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

Capsule Reviews by ALLEN J. HUBIN:

Commentary on books I’ve covered in the New York Times Book Review. [Reprinted from The Armchair Detective, Vol. 1, No. 4, July 1968.]

Previously on this blog:

Part 1 — Charlotte Armstrong through Jonathan Burke.

Part 2 — Victor Canning through Manning Coles.

STEPHEN COULTER – Players in a Dark Game. William Morrow, hardcover, 1968. Originally published in the UK as A Stranger Called the Blues: Heinemann, hc, 1968. An intrigue story in India and environs which does not live up to its promises.

S. H. COURTIER – Murder’s Burning. Random House, hardcover, 1968; paperback reprint: Popular Library, n.d. UK edition: Hammond, hc, 1967. An eerie tale of a grisly conspiracy in the Australian bush, told with a master’s skill.

JOHN CREASEY – Stars for the Toff. Walker, hardcover, 1968; paperback reprint: Lancer Lancer Books 74-606, 1970. UK edition: Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1968. This 50th adventure of Richard Rollison is good Creasey and very good Toff. Rollison is drawn into the case of Madame Melinska, a medium with impressive powers who is accused of swindling the gullible public.

AUGUST DERLETH – A Praed Street Dossier. Mycroft & Moran, hardcover, 1968. Solar Pons aficionado or not, you will be considerably pleased by this book, which should help Pons along the road to [the] larger than life immortality followed by Holmes years ago. Particularly fascinating are some 55 pages from the notebook of Dr, Lyndon Parker, who chronicled Pon’s adventures, and several chapters of marginalia on the origins of Pons and Parker.

THOMAS B. DEWEY – The King Killers. Putnam, hardcover. 1968; paperback reprint: Berkley X1665, 1969. Chicago private-eye ”Mac” is back with one of his well engineered capers, involving a murder and the neofascist League for Good Government. And you’ll enjoy an unusually attractive secondary characterization.

Sat 26 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

STEPHEN WRIGHT – The Adventures of Sandy West, Private Eye. Self-published: Mystery Notebooks Editions, large softcover, 1986.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

A recent sub-genre of the mystery is the historical set in the recent past, not a century or more ago as were some of the non-series books of John Dickson Carr. Foremost exponents of this new sub-genre, which features actual people, are Andrew Bergman and Stuart Kaminsky, but there are others, including, now, Stephen Wright, who makes his debut with The Adventures of Sandy West, Private Eye.

Try to imagine a mystery in which Dashiell Hammett, W. Somerset Maugham, Marilyn Monroe, and Humphrey Bogart play important roles. Since Sandy West is probably mystery fiction’s first bisexual detective, part of the suspense comes from trying to guess who’s going to bed with whom.

A combination of serious murder mystery and spoof of this sub-genre, it doesn’t really succeed as either but will entertain the reader willing to suspend disbelief, enjoy very erotic passages, and have some fun following the adventures of a very inexperienced detective who meets Dashiell Hammett on a train to New York immediately after World War II.

West is returning after being discharged from the U.S. Navy; Hammett is heading East to open a detective agency in New York, and he hires West. Soon West is on his first case and traveling around New York, and then Hollywood, in famous company to solve it.

Because the author, like his hero, is relatively inexperienced, there are not enough real clues or detection to make this book appeal to lovers of classic detection. Also, there is occasional repetitiveness. Sandy West drinks enough Scotch during the book to float the British Navy (and fill several pages).

Still, he is different from any other private eye I’ve read about, and it isn’t often that one can say that about a character.

Editorial Update. [09-26-09] I’ve not been able to find a cover image for this book, it may not be surprising for you to learn. I’ve not even been able to find a copy of it for sale. Marv included information as to how to order the book directly from the author, but since he died in the year 2000, I deleted it, assuming that was not likely to have done you much good, assuming of course, that you were tempted by Marv’s review into wanting a copy.

I did find an obituary for Mr. Wright online (follow the link), and in it, the following information caught my eye. “In the winter of 1984 he began yet another quarterly newsletter, Stephen Wright’s Mystery Notebook. It specialized in publishing book reviews and information on new publications in the genre, as well as original pieces by established and unknown authors.”

Has anyone seen a copy of the newsletter? Or has anyone (besides Marv) seen a copy of the book?

Next Page »