Search Results for 'Raymond Chandler'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Tue 10 Jan 2023

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

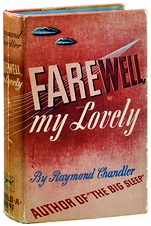

RAYMOND CHANDLER – Farewell, My Lovely. Philip Marlowe #2, Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted many times.

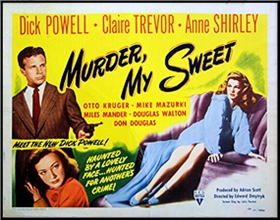

MURDER, MY SWEET. RKO, 1944. Dick Powell, Claire Trevor, Anne Shirley, Otto Kruger, Mike Mazurki and Miles Mander. Screenplay by John Paxton, from the novel Farewell, My Lovely, by Raymond Chandler. Directed by Edward Dmytryk.

I like to get back to Raymond Chandler once a year or so, and late last year it was Farewell, My Lovely (1940) a fun read enlivened by Chandler’s polished prose and feel for violence. This is the one with Marlowe getting knocked around by Moose Malloy — a character who seems to have inspired the Incredible Hulk — then waking up in a sanitarium for more sadistic fun. Add some engagingly corrupt cops, stolen whoosis and the inevitable near-fatale femme and you get a book that set the standard for a whole generation of tough mysteries.

I have to say there’s about twenty-five wasted pages — something about Marlowe trying to get on a gambling ship that takes an awfully long time to reach a plot point he could have covered by a phone call, but by and mainly, Lovely still seems fresh and surprisingly un-clichéd nearly seventy years on.

This was filmed in 1942 as The Falcon Takes Over, with George Sanders’ debonair sleuth replacing Marlowe, and under its original title in 1975, with Chandler’s archetypal detective played by Robert Mitchum, himself something of an archetype by then. But the definitive version came out in 1944 under the title Murder, My Sweet.

Murder, My Sweet ushered in film noir, and no wonder; it’s a dazzling visual thing, brightly scripted and intelligently played, the kind of movie that sets a style and inspires imitation. Director Edward Dmytryk fills the screen with monster-movie imagery — hard shadows, cobwebs, lurking things coming out of the night — and plays it off beautifully against a hard-edged, take-no-sh*t attitude. Dick Powell’s Marlowe sometimes seems petulant when he ought to look tough, but for a trend-setting film, there are remarkably few false notes played here.

Speaking of notes though, the ending of Murder, My Sweet echoes another horror-influenced film released months earlier, The Pearl of Death (Universal, 1944) one of Roy William Neill’s superior “B†Sherlock Holmes series with Basil Rathbone. Both movies end with an unarmed detective cornered in a room with Miles Mander and a hulking brute enraged by… well, you get the idea.

I only wonder what actor Miles Mander must have thought, finding himself playing out the same scene at different studios just months, or maybe weeks, apart.

Thu 11 Aug 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[12] Comments

REVIEWED BY TONY BAER:

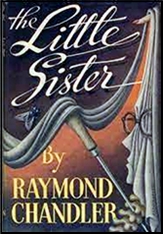

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Little Sister. Philip Marlowe #5. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1949. Reprinted many times.

A mousy little young lady, Miss Orfamay Quest from smalltown Kansas, hires Philip Marlowe to find her long lost brother. She’s terribly proper and is afraid her brother may have succumbed to the sinful temptations of Los Angeles.

The story’s as convoluted as Chandler’s usually are. But the patter is, for my money, the most hilarious of any of Marlowe’s adventures.

At first she’s not sure about Marlowe: “I don’t think I’d care to employ a detective that uses liquor in any form. I don’t even approve of tobacco.â€

“Would it be alright if I peeled an orange?†Marlowe responds.

Marlowe’s got nothing better to do, so he takes her pitifully proffered twenty dollars and gets to work on it — but not before getting Miss Quest’s description of her brother. “He used to wear a little blond mustache but Mother made him cut it off.â€

Marlowe: “Don’t tell me. The minister needed it to stuff a cushion.â€

Marlowe meets up with some heavies at brother Quest’s last known address. He takes a skiv and pistol from the first guy he sees, who says: “Maybe we meet again some day soon. When I got a friend with me.â€

Marlowe: “Tell him to wear a clean shirt…. And lend you one.†“What happens to people who get tough with you? You make them hold your toupee?â€

He meets up with a Hollywood femme fatale “almost as hard to get as a haircut.†The walls in her apartment are “monkey-bottom blueâ€. When she pleads with Marlowe that she’s lonely, he suggests she “call an escort bureau.â€

As usual, it turns out that Marlowe’s client is full of shit. Miss Quest knows precisely where her brother is all along and she’s just trying to squeeze her way into his blackmail scheme against their much more successful Hollywood starlet of a half-sister. They’ve got some dirt on good old sis that ties her to the mob and they want to bleed her for all she’s worth.

Invited to join in the blackmail, Marlowe demurs: “I’d never get anywhere as a blackmailer. I just don’t have the engaging personality.â€

There’s murder and drugs and backstabbing galore, and Marlowe comes as close as ever to imprisonment and losing his license.

Marlowe metes out justice in his own idealistic ways, protecting the innocent at his own peril, while doing his best to make sure that the guilty get theirs, whether via the law or other more karmic means.

The book is one of Marlowe’s more neglected and maligned. But for me, it’s one of his best.

Fri 26 Nov 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

CHANDLER: Stories & Early Novels and CHANDLER: Later Novels & Other Writings. Two-volume set. Library of America, hardcover, 1995.

If you, like me, think that any mystery collection is inadequate and incomplete without the works of Raymond Chandler; and you, like me, have acquired his books in mass paperback because you couldn’t afford them in hard covers; and you, like me, have harbored a forlorn wish to have them in a more permanent and respectable yet not outrageously expensive form; then here is what we’ve both been waiting for.

Since 1982 the Library of America, “an award-winning, non-profit publishing program dedicated to publishing America’s greatest writers in handsome, enduring volumes,” has been doing just that, and the Chandler set makes up the 80th and 81st volumes they have issued.

In the two volumes you’ll find all of Chandler’s novels, the thirteen short stories that he did not later incorporate into a novel, selected essays and letters, and the screenplay he wrote with Billy Wilder for Cain’s Double Indemnity. The 1199 and 1076 page volumes also each include notes and an excellent updated chronology of Chandler’s life by Frank McShane.

These are superbly produced books that bring the essence and essential works of Chandler together in an accessible and affordable form. At $35 the volume they represent as fine a value as you’re likely to find in the field in these days of $24 first novels and $7 paperbacks. If you don’t already own Chandler in hardcovers — and how many of us do? — you need to own these.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #22, November 1995

Mon 13 Apr 2020

RAYMOND CHANDLER “Wrong Pigeon.†Short story. PI Philip Marlowe. First magazine publication in Manhunt, February 1960. Previouslypublished, possibly in abridged form, in a British newspaper as “Marlowe Takes on the Syndicate.†Later reprinted as “Philip Marlowe’s Last Case†in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (January 1962) and as “The Pencil” in Argosy (September 1965). Collected as “The Pencil†in The Smell of Fear (H. Hamilton, UK, 1965). Reprinted in Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe: A Centennial Celebration, edited by Byron Preiss (Knopf, 1988) and as “Wrong Pigeon†in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carroll & Graf, 1988), among others. TV adaptation: As “The Pencil†on Philip Marlowe, Private Eye, 16 April 1983 (season 1, episode 1), starring Powers Boothe.

And with all of that, I’ve still probably missing something obvious. It was, as the title of the story as it appeared in EQMM, PI Philip Marlowe’s last case, Raymond Chandler having died in 1959, and it’s a good one. Marlowe takes on a job for a guy who wants to get out of the mob, but there’s been a pencil drawn through his name, and he knows the syndicate does not take defections lightly.

It’s a fool’s task, but the promise of $5000 upon completion of a successful escape has a loud way of talking, and that’s in 1959 money. And Marlowe is no fool. He knows that there’s a reason why the job is done so easily. He’s right, of course, and you should be. too, the reader.

It’s been a long time for me to get around to reading this one, and I’m glad I did. I don’t know what the general opinion is of this story, but I think Chandler was still in fine form when he wrote it. The story is light and breezily told, but when it comes down to it, Marlowe is as hardboiled as private eyes really ought to be, especially when it comes to dealing with the syndicate. Very enjoyable.

Sat 28 Mar 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Simple Art of Murder. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1950. Pocket #916, paperback, 1953. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and paperback.

Eleven of the twelve stories in is collection are those that Chandler considered the best of his output for the pulps; the other story, “I’ll Be Waiting†was first published in the Saturday Evening Post (although Chandler admittedly felt uncomfortable and restricted writing for the slick-magazine medium). Also included here is Chandler’s famous and controversial essay on detective fiction, first published in the Atlantic Monthly, in which he lauds Hammett and the realistic school of crime writing, and takes a number of shots (some fair, some cheap) at such Golden Age luminaries as Christie, Sayers, and A. A. Milne.

The stories here, as the dust jacket blurb says with typical publishers’ overstatement bur accurately nonetheless “hit you as hard as if [Chandler] were driving the last spike on the first continental railroad.” “Red Wind,” for instance, begins with one of the finest opening paragraphs in the history of the genre:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of the hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edges of carving knives and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.

In the original appearance of that story, the private-eye narrator was Johnny Dalmas; here he becomes Philip Marlowe. Similarly, the unnamed narrator in “Finger Man,“ Carmady in “Goldfish,” and Dalmas again in “Trouble 1s My Business” are also changed to Marlowe. Johnny Dalmas does get to keep his own name in “Smart-Aleck Kill,” no doubt because that novelette is told third-person.

And the same is true of Carmady in “Guns at Cyrano’s.†The only other first person story in the collection, the lighter-toned and somewhat wacky “Pearls Are a Nuisance,” features a much more refined dick named Walter Gage whose antics in search of a string of forty-nine matched pink pearls provide chuckles as well as thrills. Also included arc the tough Black Mask novelettes “Nevada Gas” and “Spanish Blood,” “The King in Yellow†from Dime Detective and “‘Pick-Up on Noon Street” from Detective Fiction Weekly.

All of these stories appear in several other collections, such the paperback originals Five Murderers (1944) and Finger Man and Other Stories (1946) and the Tower Books hardcover originals Red Wind (1946) and Spanish Blood (1946). Next to The Simple Art of Murder, the most interesting and important Chandler collection is Killer in the Rain (1964), which gathers the eight “cannibalized” stories that were used as the bases for The Big Sleep, Farewell. My Lovely, and The Lady in the Lake.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sat 21 Mar 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Long Goodbye. Philip Marlowe #6. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1954. Pocket #1044, paperback, 1955. Reprinted many time, both in paperback and hardcover. TV adaptation: “The Long Goodbye” on Climax, 07 Oct 1954. with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe. Film: United Artists, 1973, with Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe.

The title of this novel is apt. It is a long book and a complex one, and its detractors say they wish Chandler had said goodbye two-thirds of the way through. What these critics fail to understand is that the novel is one of the most realistic looks into the day-to-day life of a private investigator, and the central plot element, that of Philip Marlowe’s friendship for the mostly undeserving Terry Lennox, is a compelling unifying element. In it we also see a different side of Marlowe than in Chandler’s other novels: the man who is as honorable in his personal relationships as he is in his professional ones.

The story begins when Marlowe first sees Terry Lennox, dissolute man-about-town: he is “drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of the Dancers,†a ritzy L.A. nightspot, with a redheaded girl beside him whose blue mink “almost made the Rolls Royce look like just another automobile.” The girl leaves Terry, Good Samaritan Marlowe takes over, and a friendship begins.

It is a friendship that Marlowe himself questions, but it persists nonetheless. Marlowe tells Lennox he has a feeling Terry will end up in worse trouble than Marlowe will be able to extricate him from. and in due course this proves true. The redhead, Terry’s ex-wife, whom he admittedly married for her money, is murdered in the guesthouse at their Encino spread and the trouble that Marlowe sensed begins.

Lennox runs to Mexico, and it is reported that he made a written confession and shot himself in his hotel room. But something feels wrong: The Lennox case is being hushed up, and Marlowe begins to wonder if his friend really did kill his ex-wife. A letter that arrives with a “portrait of Madison” – a $5000 bill that Terry had once promised Marlowe – convinces him his suspicions are justified.

He tells himself it is over and done with, but he isn’t able to forget. The matter plagues him while he is working a case involving an alcoholic writer of best sellers in wealthy Idle Valley (where, he says, “I belonged … like a pearl onion on a banana split”). It begins to plague him even more when Sylvia Lennox’s sister, Linda Loring, appears and plants additional suspicions in his mind. The suspicions spur him onward, and finally his current case and the Lennox case come together in a shattering climax.

At the end Chandler neatly ties off all the strands of this complicated story, and provides more than a few surprises. An excellent novel with a moving ending.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 17 Mar 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

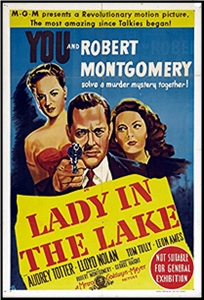

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Lady in the Lake. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1943. Pocket #389, paperback; 1st printing, September 1946. Film: MGM, 1946, as Lady in the Lake (with Robert Montgomery as Philip Marlowe).

Even though The Lady in the Lake is not Chandler’s best novel. it is this reviewer’s favorite. It too was “cannibalized” from three pulp novelettes: “Bay City Blues·” (Dime Detective, November 1937), “The Lady in the Lake” (Dime Detective, January 1939), “No Crime in the Mountains” (Detective Story, September 1941), but it is not as seamless as The Big Sleep or Farewell, My Lovely, nor as wholly credible. Nevertheless. there is an intangible quality about it, a kind of terrible and perfect inevitability that combines with such tangibles as Chandler’s usual fascinating assortment of characters and some unforgettable moments to make it extra satisfying.

The novel opens with Marlowe hired by Derace Kjngsley, a foppish perfume company executive, to find his missing wife. Crystal (who he admits he hates and who may or may not have run off with one of his “friends,” Chris Lavery). Marlowe follows a tortuous and deadly trail that leads him from L.A. to the beach community of Bay City, to Little Fawn Lake high in the San Bernardino Mountains, to the towns of Puma Point and San Bernardino, and back to to L.A. and Bay City. And it involves him with a doctor named Almore, a tough cop named Degarmo, a half-crippled mountain caretaker, Bill Chess, whose wife is also missing, Kingsley’s secretary, Miss Adrienne Fromsett and the lady in the lake, among other victims.

As the dust jacket or the original edition puts it, it is “a most extraordinary case, because … Marlowe understands that what is important is not a clue – not the neatly stacked dishes, not the strange telegram … but rather the character of [Crystal Kingsley]. When he began to find out what she was like, he took his initial steps into a world of evil, and only then did the idea of what she might have done and what might have been done to her take shape. So it was that not one crime but several were revealed, and a whole series of doors that hid cruel things were suddenly opened.

“Again Chandler proves that he is one of the most brilliant craftsmen in the field, and that his Marlowe is one of the great detectives in fiction.”

Amen.

The Lady in the Lake was filmed in 1946. with Robert Montgomery (who also directed) as Marlowe. For its time, it was a radical experiment in film-making, in that it is entirely photographed as if through the eyes of Marlowe — a sort of cinematic version of the first-person narrator, with Montgomery himself never seen except in an occasional mirror reflection. The technique doesn’t quite work – it, not the story, becomes the focus of attention – but the film is an oddity worth seeing.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 28 Feb 2020

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

RAYMOND CHANDLER – Farewell My Lovely. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1940. Pocket Book #212, paperback, 1943. Reprinted many times.

Many critics consider The Long Goodbye to be Chandler’s finest novel. This one disagrees. That distinction should probably go to Farewell, My Lovely – a more tightly plotted, less self-indulgent and overblown book, with characters, scenes, and prose of such artistry that it ranks as not only a cornerstone private-eye novel but a cornerstone work in the genre. Its near-flawless construction is all the more awesome when you consider that like The Big Sleep, it is a product of “canniballzation”: It makes extensive use of “The Man Who Liked Dogs” (Black Mask, March 1936); “Try the Girl” (Black Mask, January 1937); and “Mandarin’s Jade” (Dime Detective, November 1937).

Marlowe’s client in this case is Moose Malloy, a giant ex-con with a one-track mind: All that matters to him is finding his former girlfriend, Velma, a redhead “cute as lace pants,” who disappeared after he was sent to prison. Marlowe is a reluctant detective, his first encounter with Malloy having ended in the wreckage of a bar, Florian’s, where Velma once worked and a black bouncer suffering a broken neck; but Malloy won’t take no for an answer.

As Marlowe’s search for Velma develops, “the atmosphere becomes increasingly malevolent and charged with evil.” Among the characters he meets are a foppish blackmailer named Lindsay Marriott; a gin-drinking old lady with secrets and a fine new radio; a beautiful blonde with no morals and a rich husband who doesn’t give a damn; a Hollywood Indian named Second Planting who has “the shoulders of a blacksmith and the … legs of a chimpanzee”; a phony psychic, Jules Amthor: Dr. Sonderborg, who runs a private psychiatric clinic staffed with thugs; Laird Brunelle, the tough operator of a gambling ship called the Royal Crown; and L.A. and Bay City cops, some of whom are as crooked as a dog’s hind leg.

The climax, in which Marlowe and Moose Malloy both come face-to-face with the elusive Velma, is a stunner. Like a number of other scenes — especially Marlowe’s drugged imprisonment in Sonderberg’s clinic, in a room “full of smoke [that] hung straight up in the air, in thin lines, straight up and down like a curtain of small clear beads”-it remains sharp in one’s memory long after reading.

Farewell. My Lovely was filmed twice, once in 1944 as Murder, My Sweet, With Dick Powell as Marlowe, and once in 1975 under its original title, with Robert Mitchum in the starring role. The Powell version is the better of the two, even though Mitchum, aging and slightly seedy, better captures the essence of Marlowe. (Powell isn’t bad, though-a surprisingly gritty performance for an actor who began his career as a crooner in Busby Berkley musicals.) Mike Mazurki’s portrayal of Moose Malloy in Murder My Sweet is more memorable (and credible) than Jack O’Halloran’ s in Farewell. And the noir style of the earlier film better captures the flavor of Chandler’s work than the arty, full-color remake.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 22 Jan 2020

SELECTED BY DAN STUMPF:

RAYMOND CHANDLER “English Summer.” Written in 1957; first printed in The Notebooks of Raymond Chandler, edited by Frank MacShane (Ecco Press, hardcover, 1976).

A story that went unpublished in Chandler’s lifetime, and it’s easy to see why. But an excellent work nonetheless, and one of his best in the short story medium — which is saying a lot.

According to Chandler’s notes (recorded in Raymond Chandler Speaking) he saw “English Summer†as a break-out work, one that would re-define his writing for the future. Hence, the first few pages read like he’s trying to change his accustomed style, and the result is a little constrained and sort of self-consciously Hemingwayesque.

Fortunately, Chandler can’t keep up the strain of not writing like Chandler for long, and we are soon back into the familiar and uniformly excellent prose of a great writer at his best and when we get into the story proper….

Yeah. This is a creepy one. The narrator, John Paringdon, is hopelessly in love with Millicent Crandall, who is married to an abusive and neglectful drunk. He is in fact a guest at their country cottage, the sort of situation that should lead to a weekend of brittle dialogue, but Chandler observes the unities here. At break of day Paringdon goes for a walk and meets the bewitching Lady Lakenham. By sunset he will be in love with no one.

This being Chandler, there’s murder involved, done casually as dust swept under a casket. There’s also cold-blooded seduction committed by Lady Lakenham, in a castle hacked to pieces by her husband.

We even get the sort of cross-country flight from the authorities one finds in the chase novels of John Buchan. But that’s not what “English Summer†is about.

“English Summer†is about the death of Love. And it comes from a writer who once observed that in a mystery, the crime is (or should be) less important than its effect upon the characters — brilliantly realized here in a few pages that will haunt me for a long time.

Tue 15 Oct 2019

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Big Sleep. Philip Marlowe #1. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1939. Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #7, digest paperback, 1942; New Avon Library [#38], paperback, 1943. Movie photoplay edition: World, hardcover, 1946. Reprinted many times since. Film: Warner Bros., 1946 (screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman; director Howard Hawks; Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe). Also: United Artists, 1978 (screenwriter-director: Michael Winner; Robert Mitchum as Marlowe).

It is difficult to imagine what the modern private eye story would be like if a forty-five-old ex-oil company executive named Raymond Chandler had not begun writing fiction for Black Mask in 1933. In his short stories and definitely in his novels, Chandler took the hardboiled prototype established by Dashiell Hammett, reshaped it to fit his own particular vision and the exigencies of life in southern California, smoothed off its rough edges, and made of it something more than a tale of realism and violence; he broadened it into a vehicle for social commentary, refined it with prose at once cynical and poetic, and elevated the character of the private eye to a mythical status — “down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.”

Chandler’s lean, tough, wisecracking style set the tone for all subsequent private-eye fiction, good and bad. He is certainly the most imitated writer in the genre, and next to Hemingway, perhaps the most imitated writer in the English language. (Howard Browne, the creator of PI Paul Pine, once made Chandler laugh at a New York publishing party by introducing himself and saying, “It’s an honor to meet you, Mr. Chandler. I’ve been making a living off your work for years.”

Even Ross Macdonald, for all his literary intentions, was at the core a Chandler imitator: Lew Archer would not be Lew Archer, indeed might not have been born at all, if Chandler had not created Philip Marlowe.

The Big Sleep , Chandler’s first novel, is a blending and expansion of two of his Black Mask novelettes, “Killer in the Rain” (January 1935) and “The Curtain” (September 1936) — a process Chandler used twice more, in creating Farewell, My Lovely and The Lady in the Lake, and which he candidly referred to as “cannibalizing.”

It is Philip Marlowe’s first bow. Marlowe does not appear in any of Chandler’s pulp stories, at least not by name: the first person narrators of “Killer in the Rain” (unnamed) and “The Curtain” (Carmody) are embryonic Marlowes, with many of his attributes. The Big Sleep is also Chandler’s best-known title, by virtue of the well-made 1944 film version directed by Howard Hawks and starring Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Elisha Cook, Jr.

On one level, this is a complex murder mystery with its fair share of clues and corpses. On another level, it is a serious novel concerned (as is much of Chandler’s work) with the corrupting influences of money and power. Marlowe is hired by General Sternwood, an old paralyzed ex-soldier who made a fortune in oil, to find out why a rare-book dealer named Arthur Gwynn Giger is holding his IOU signed by Sternwood’s youngest daughter, the wild and immoral Carmen, and where a blackmailing abler named Joe Brody fits into the picture.

Marlowe’s investigation embroils him with Sternwood’s other daughter, Vivian, and her strangely missing husband, Rusty, a former bootlegger; a thriving pornography racket; a gaggle of gangsters, not the least of which is a nasty piece of work named Eddie Mars; hidden vices and family scandals; and several murders. The novel’s climax is more ambiguous and satisfying than the film’s rather pat one.

The Big Sleep is not Chandler’s best work; its plot is convoluted and tends to be confusing, and there are loose ends that are never explained or tied off. Nevertheless, it is still a powerful and riveting novel, packed with fascinating characters and evocatively told. Just one small sample of Chandler’s marvelous prose:

The air was thick, wet, steamy and larded with the cloying smell of tropical orchids in bloom. The glass walls and roof were heavily misted and big drops of moisture splashed down on the plants. The light had a unreal greenish color, like light filtered through an aquarium. The plants filled the place, a forest of them, with nasty meaty leaves and stalks like the newly washed fingers of dead men. They smelled as overpowering as boiling alcohol under a blanket.

That passage is quintessential Chandler; if it doesn’t stir your blood and make you crave more, as it always does for this reviewer, he probably isn’t your cup of bourbon.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.