REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

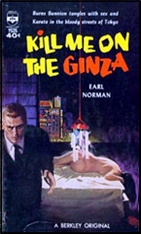

EARL NORMAN – Kill Me on the Ginza. Burns Bannion #6. Berkley Y626, paperback original, 1962. Barye Phillips cover art. Also available in ebook format (Kindle).

You know the old saying, “you can’t keep a good thing down?†It seems sometimes you can’t keep a bad thing down either, which explains why Earl Norman’s Burns Bannion novels are back in print.

Burns Bannion is an expatriate American private eye in Tokyo (each book gives us a long winded explanation how the Japanese would never give an American a P. I. License so Bannion is enrolled as a college student, but never goes to class), and an expert in karate. Literally the little bits of karate you get in these slender books is about the only reason to read them though they promised at times to be so bad they are good without quite making it.

This one opens with our hero in a club on the Ginza, the neon club district in wide open Post War Tokyo, Burns is leaving a club when a pneumatic Japanese performer heaving precariously in her low cut outfit smacks him over the head with a metal tray.

“See fat slob! See big hunk! This Burns Bannion! This Tokyo private tante, Snooper! Detective! Lousy Bastard!â€

So far I can’t disagree with anything she says.

This is really poverty row private eye stuff with a little international intrigue and exotic locations thrown in. In every book Bannion meets one dimensional (character wise, physically they are three dimensional) Japanese women in various states of undress and gets drawn into pretty non-dimensional cases.

Bannion fails to recognize this one because she has her clothes on, and he last saw her a week earlier in the buff posing at the Art Photography Studio for Photo Fans also on the Ginza (next to the Urological and Sexual Institute we are told) where Bannion had pretended to be a photographer to check her out for a client, Hedges, a correspondent. Seems the girl, G. N. Noriko was a friend of Bill Crea a missing correspondent who disappeared on a trip to Kobe.

Before he can go to Kobe though Inspector Ezawa, another Karate man, picks up Bannion and Hedges and takes them to the train station where a dismembered body has been found, and the police have been sent his head in a bowling bag. Bill Crea’s head.

Not a terrible opening despite Norman’s somewhat tiresome version of wise guy private eye-ese. In this one he’s battling a cult, the Oshira, based on a prototype of modern Japanese gods and predating Buddhism, the hidden god, and something called the Grand Apex which turns out to be a front for sex trafficking from Korea while Bannion gets help from G. N. (and you do not want to know what those initials stand for) and a stripper called Bay-bee.

There’s also a philosophical criminal called House Charnel who talks like Nietzsche on LSD: “We are all born into the world as enemies.â€

I can see where these time killers were exotic enough at the time to draw some readers. The plots are serviceable, there is a lot of talk about sex and pneumatic Japanese beauties, and of course karate battle aplenty (I wanted to get my hands free so I could Karate-chop the Whore-master to his just rewards.).

I have a feeling that many people feel more kindly about these than I do, and I have no problem with that.

I will give Norman this, he manages to keep the action boiling down to the last page and without a single chapter break — that’s right, the edition I read had no chapter breaks, just continuous narrative, and I have a suspicion this may be his best book, though that isn’t saying a lot. He knows something about Japan and probably could have parlayed that into something interesting, but never does.

The Burns Bannion series —

Kill Me in Tokyo. Berkley 1958 [Tokyo]

Kill Me in Shimbashi. Berkley 1959 [Tokyo]

Kill Me in Yokohama. Berkley 1960 [Japan]

Kill Me in Shinjuku. Berkley 1961 [Tokyo]

Kill Me in Yoshiwara. Berkley 1961 [Tokyo]

Kill Me in Atami. Berkley 1962 [Japan]

Kill Me on the Ginza. Berkley 1962 [Tokyo]

Kill Me in Yokosuka. Erle 1966 [Japan]

Kill Me in Roppongi. Erle 1967 [Japan]