Thu 10 Mar 2011

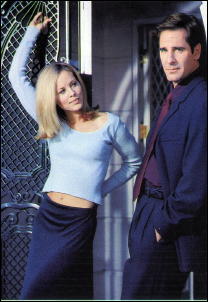

A TV Series Review by Michael Shonk: MR. & MRS. SMITH (1996).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[21] Comments

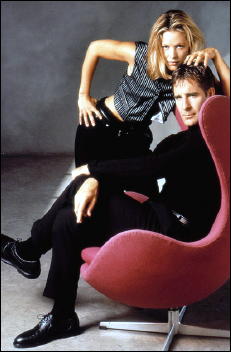

MR. & MRS. SMITH. CBS. September 20, 1996 through November 8, 1996. Cast: Mr. Smith: Scott Bakula, Mrs. Smith: Maria Bello, Mr. Big: Roy Dotrice, Rox: Aida Turturro (two episodes). Created by Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar.

Mr. & Mrs. Smith was a better than average mindless TV romantic comedy mystery.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith worked for The Factory, a worldwide private intelligence firm with the latest gadgets and unlimited resources. The company was run by a man known as Mr. Big. The Factory had a rule that no agent could know anything about another agent’s past. So, while off saving the world and solving crimes, the Smiths spent their free time trying to uncover the other’s secret past. Why they don’t even know the other’s name!

If this secret past bit sounds like Remington Steele doubled, it was not by accident. Creators Lenhart and Sakmar were on the writing staff of Remington Steele during the third and fourth seasons. Michael Gleason, co-creator and showrunner of Remington Steele, wrote the final episode of Mr. & Mrs. Smith.

The series had an interesting twist to the overdone “will they or won’t they” cliche. At times, she was willing to hop into bed with him, and he was tempted, but there was something in his past stopping him.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith were complete opposites, and on TV that makes them the perfect team. She was talkative and impulsive while he was quiet and deliberate. If one did not know something, the other was an expert on the subject.

The sexual attraction each had for the other was understandable. However, the two leads’ chemistry did not heat up the screen. Scott Bakula gave his usual performance, ranging from wooden to over the top. Maria Bello was a wonderful surprise, with an emotionally expressive face able to reveal Mrs. Smith’s damaged past without a word.

The writing was typical television, ranging from great fun to embarrassingly bad. The mysteries relied more on twists, but did feature an occasional obvious clue. The stories’ pace were fast enough, so if you turned off your brain, you did not care about the, at times, unbelievably stupid behavior of the characters.

The best clues were not for the mystery of the week, but for the arc story of the mystery of Mr. and Mrs. Smiths’ pasts. The characters and their relationship evolved each week as they learned more about each other.

Sadly, CBS aired only nine of the thirteen episodes, and at least two were noticeably out of order. In “The Grape Escape”, Mr. Smith goes through Mrs. Smith’s hidden trunk of past mementos. But it is a trunk the viewer and Mr. Smith did not know existed until “The Publishing Episode” that aired the week after.

Without the last four episodes, the viewers missed out on the satisfying ending to the central mystery of the characters’ pasts.

The final four episodes were aired sometime overseas. All thirteen episodes are available at You Tube. No DVD is currently legally available.

EPISODE INDEX

Pilot (9/20/96) Written: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Directed: David S. Jackson. Mr. Smith meets the future Mrs. Smith while each, on opposite sides, attempt to find a missing scientist who had invented a new energy source.

The Suburban Episode (9/27/96) Written: Mitchell Burgess and Robin Green. Directed: Oz Scott. The Smiths move to the suburbs of St. Louis and pose as new neighbors to a man suspected of selling top-secret government codes.

The Second Episode (10/4/96) Written: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Directed: Ralph Hemecker. Mr. and Mrs. Smith help a bumbling assistant stop his boss from selling arms to a terrorist.

The Poor Pitiful Put-Upon Singer Episode (10/11/96) Written: Del Shores. Directed: Nick Marck. The Smiths try to find out whom wants to kill the head of a small record label.

The Grape Escape (10/18/96) Written: Susan Cridland Wick. Directed: Daniel Attias. The Factory sends the Smiths on a mission to save the vineyards of Europe from a scientist’s bug bombs.

The Publishing Episode (10/25/96) Written: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: James Quinn. The Smiths have to stop the sale of a tell-all spy book written by a missing British spy named Steed. Each Smith wants to find the book first, so to read about the other’s past.

The Coma Episode (10/28/96) Written: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: Michael Zinberg. Mr. Smith plays doctor with Mrs. Smith taking the role as coma patient so they can get closed the a guarded coma victim that knows the plans of terrorists to attack a peace conference.

The Kidnapping Episode (11/1/96) Written: Mitchell Burgess and Robin Green. Directed: Sharron Miller. Before the Smiths can discover who is causing problems at a drug company, their client is kidnapped.

The Space Flight Episode (11/8/96) Written: Michael Cassutt. Directed: Lou Antonio. When an ex-astronaut hires The Factory to find a space prototype and his son, the trail leads the Smiths to Area 51.

The Big Easy Episode (never aired on CBS) Written: Del Shores. Directed: James Whitmore Jr. The Smiths visit New Orleans when The Factory is hired to clear a Senator’s mistress of a conviction for selling government secrets.

The Impossible Mission Episode (never aired on CBS) Teleplay: Kerry Lenhart and John J. Sakmar. Story: Douglas Steinberg. Directed: Artie Mandelberg. The Smiths help fellow Factory agents, the Jones, trap some counterfeiters.

The Bob Episode (never aired on CBS) Written: Sanford Golden. Directed: Jonathan Sanger. Bob, a friend from Mr. Smith’s pre-spy days, gets caught in the middle between the Smiths and a terrorist with enough plutonium to make an atomic bomb.

The Sins of the Father (never aired on CBS) Written: Michael Gleason. Directed: Rob Thompson. Mr. Smith disappears while in mid-assignment when he is blackmailed with his past. While The Factory writes him off, Mrs. Smith rushes to his rescue, whether he wants her to or not.