Fri 14 Jan 2011

Mike Nevins on ELLERY QUEEN (DANNAY & LEE) & PATRICIA HIGHSMITH.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Old Time Radio , TV mysteries[11] Comments

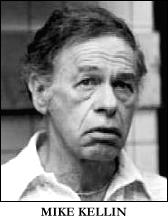

by Francis M. Nevins

I recently unearthed an Ellery Queen mystery, or more precisely a mystery about EQ, which will not be solved easily if at all. The September 2002 issue of Radiogram, a magazine for fans of old-time radio, includes “In the Studio with Ellery Queen,†a brief memoir by Fred Essex, who was a producer-director for the Ruthrauff & Ryan advertising agency in the early 1940s when one of the programs the agency brought to the air every week was The Adventures of Ellery Queen.

At this time Ellery’s creators, the cousins Fred Dannay and Manny Lee, were working out of an office in mid-Manhattan but asked the agency not to disturb them while they were in the throes of creation. “[T]he boys in the mail room who would deliver two mimeographed copies of the finished script each week were instructed not to enter the office…but to throw the fat envelope through the transom above the door.â€

At the time in question, Essex recalled, “Carleton Young played Ellery….†We know that Young took over that role in January 1942, when the series returned to the air after a 15-month hiatus, and kept it until August or September 1943 when he was replaced by Sydney Smith. Essex occasionally directed an EQ episode, and in his memoir described a segment where the murder “was committed in a radio studio that was supposedly rehearsing a crime program.â€

Essex recalled that the guest armchair detective that evening was radio comedian Fred Allen, and that he failed to solve the mystery. What’s wrong with this picture? Simply that The Sound of Detection, my book on the Queen series, lists no episode during Young’s tenure where Ellery solved a crime in a radio studio and no episode at any time where Fred Allen was the armchair sleuth!

Either Essex misremembered radically or there’s still some information on the Ellery of the airwaves that hasn’t been unearthed. I hope to live long enough to find out which.

Anyone in the market for another EQ mystery? As most mysteryphiles know, roughly between 1960 and 1966 Manny Lee was suffering from some sort of writer’s block and unable to collaborate with Fred Dannay as he’d been doing so successfully since 1929.

Ellery Queen novels and shorter adventures continued to appear during those years, with other authors expanding Fred’s lengthy synopses as Manny had always done in the past. We know who took over Manny’s function on the novels of that period but not on the short stories and not on the single Queen novelet from those years.

“The Death of Don Juan†(Argosy, May 1962; collected in Queens Full, 1965) is set in Wrightsville and deals with the attempt of the town’s amateur theatrical company to stage a creaky old turn-of-the-century melodrama.

Could this be a clue to the identity of Fred’s collaborator on the tale? In his graduate student days Anthony Boucher had worked in the Little Theater movement, and on his first date with the woman he later married the couple went to a creaky old-time melodrama.

This is hardly conclusive evidence but, if I may borrow a Poirotism, it gives one furiously to think. Between 1945 and 1948 Boucher had taken over Fred’s function of providing plots for Manny to transform into finished scripts for the EQ radio series. Might he also have performed Manny’s function a dozen or more years later?

The first publisher of the hardcover Ellery Queen novels and anthologies was the Frederick A. Stokes company, with whom Fred and Manny stayed from their debut in 1929 until 1941. A few months before Pearl Harbor they moved to Little, Brown and stayed there through 1955.

After a few years with Simon & Schuster (1956-1958) they moved to Random House and the aegis of legendary editor Lee Wright (1902-1986), who among other coups had purchased Anthony Boucher’s first detective novel and the first “Black†suspense novels by Cornell Woolrich.

What was behind their earlier moves from one publisher to another remains unknown, but when I interviewed Wright more than thirty years ago she explained why Queen left Random House. The year was 1965, a time when Manny was suffering from writer’s block and Fred called most of the shots for the two of them.

He left Random, Wright told me, â€literally because Bennett Cerf didn’t invite him to lunch. His feelings were hurt….I said: ‘Fred, Bennett isn’t your editor. I am. You’re sort of insulting me. My attention isn’t enough for you, it has to be the head of the house, is what you’re saying.’â€

Fred tended to be hypersensitive to any hint that mystery writers were second-class literary citizens, while Manny over the years had come to hate the genre and his own role in it, to the point that he described himself to one of his daughters as a “literary prostitute.â€

That he and Fred could have disagreed about this and everything else and still have collaborated successfully for so long is nothing short of a miracle.

When I was ten years old, for no particular reason I began squirreling away the weekly issues of TV Guide as my parents threw them on the trash pile with the week’s newspapers. The result is that today my bookshelves are weighed down by a week-by-week history of television from the early Fifties till the end of 2000, a goldmine of information unavailable elsewhere.

One such nugget is buried in the listings for Thursday, June 14, 1956. One of the top Thursday night programs broadcast that season was the 60-minute live dramatic anthology series Climax!

That particular evening’s offering was “To Scream at Midnight,†in which a wealthy young woman breaks down and is placed in a sanitarium after being thrown over by her lover. Her psychiatrist becomes suspicious when the man reappears and claims he wants to marry her.

Heading the cast were Diana Lynn (Hilde Fraser), Dewey Martin (Emmett Shore), Karen Sharpe (Peggy Walsh), and Richard Jaeckel (Hordan). John Frankenheimer directed from a teleplay by John McGreevey which, according to TV Guide, was based on something by Highsmith.

But what? I can recall no novel or story by her from 1956 or earlier (or later either) that remotely resembles this plot summary, but I am no authority on Highsmith. Joan Schenkar, author of the Edgar-nominated The Talented Miss Highsmith (2009), has read every word her subject ever wrote, including hundreds of thousands of words in her diaries.

When I sent her a photocopy of the relevant TV Guide page, she too couldn’t connect the description with any Highsmith novel or story.

That makes three mysteries about mysteries in one column, all of them probably unsolvable. If any readers have suggestions I’d love to see them.

Breaking News! My chance encounter last Thanksgiving with that website devoted to William Ard has borne fruit. Ramble House, a small publisher with which every reader of this column should be acquainted, has arranged with Ard’s daughter to reprint a number of her father’s novels of the Fifties, probably in the two-to-a-volume format pioneered by Ace Books back when Ard was turning out four or more paperback originals a year. More details when I have them.