FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

As a novice widower I find myself thinking of three other mystery writers who lost wives to Mister Death. The first name that springs to mind in this connection is Raymond Chandler (1888-1959), who was so devastated by the death of his wife Cissie that he tried to shoot himself in his bathroom.

Being blind drunk at the time, he missed his target. “She was the music heard faintly at the edge of sound…†he said of Cissie. “She was the light of my life, my whole ambition. Anything else I did was just the fire for her to warm her hands at.â€

Next comes Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), whom I never met but have been associated with for most of my life. He married the former Hazel Goodwin in 1919 and they were together until she died of cancer in May 1960.

During the months of her final illness and after her death he was unable to write fiction, but he continued sending out his off-the-wall “Walter Keyhole†newsletters to just about everyone whose address he had.

He called them polychromatic or multitinctorial cartularies since each page was printed on paper of a different color. We who have lived into the computer age recognize them as the functional equivalent of a blog. It cost him as much as $50 to have each installment prepared by a professional typing service and mailed out en masse.

I have originals or photocopies of 188 of these, which a few years ago I organized and offered to a panting public as The Keeler Keyhole Companion (2005). Among the hundreds of topics he touched on was his life as a lonely widower in his early seventies, “a guy who lives on canned Campbell’s soups and canned Sultana pork and beans.â€

Here’s his account of the “long lonely Thanksgiving holiday†in 1962. “We [he often uses the royal we in these cartularies] had our choice of having 3 soft-boiled eggs (only thing we can cook) as a dinner, then seeing the Three Stooges conk each other over the heads [at the local movie house], or of having 3 soft-boiled eggs as a dinner and re-reading Keyser’s Mathematical Philosophy. You guess!â€

I now feel closer to that genuine mad genius than ever before. He was only a year or two older at his wife’s death than I at Patty’s. He sold the old house they had lived in for decades and moved into an apartment hotel, while I’ve recently bought a condo and put my own Toad Hall on the market. I’m no better at cheffery than Harry was but have the advantage of living in the age of that fantastic contraption known as the microwave.

The third author in whose moccasins I now walk became a widower not once but twice. Fred Dannay (1905-1982), better known as Ellery Queen, married the former Mary Beck in 1926. She died of cancer on July 4, 1945, leaving Fred with two small children to raise.

In 1947 he married the former Hilda Wiesenthal, who was ten or eleven years younger than he and was the daughter of a cousin of Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. She died in 1972, also of cancer.

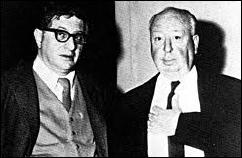

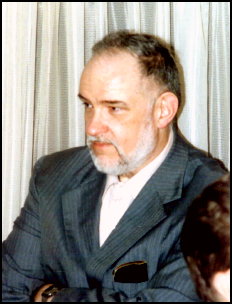

By that time I had come to know Fred well and he had become the closest thing to a grandfather I had ever known. I went through this awful period of his life with him. There’s a photograph of him taken at this time which shows the empty devastated face of a man waiting for the dark to claim him.

Just as Keeler had married again a few years after Hazel’s death, so did Fred a few years after Hilda’s. I got to know Thelma Keeler well and am convinced that she saved her husband’s life. I also have no doubt that Fred’s third marriage, to the former Rose Koppel, saved his. Will I luck out in my final years as they did?

I apologize for devoting so much of this column to death but I really don’t have much choice at the moment. Less than a week before Christmas I learned that I’d lost one of my closest mystery-loving friends.

Bob Briney was something of a universal genius. Physically he evoked Orson Welles or Nero Wolfe but was soft-spoken and totally without their irascibility and moved with a certain gingerliness as if he were afraid he’d crush something if his movements were more forceful.

He was born near Benton Harbor, Michigan in December 1933 and spent most of his academic career in Massachusetts, at Salem State University. He earned a Ph.D. in mathematics and recovered from the ordeals of his dissertation and orals, so he told me, by reading most of the novels of John Dickson Carr in less than a month.

Like the clever men of Oxford in The Wind in the Willows, he “knew all that was to be knowed‗about mystery fiction, fantasy, s-f, horror, Westerns, just about every form of popular fiction you can name, plus ballet and opera and movies and classical music and so much more.

His ability to keep prodigious masses of data in perfectly organized form would have shamed many a computer. He wrote prolifically and with dry wit about books and authors, assiduously collected works in the genres he loved — every room in his large house including the bathroom was a library first and foremost — and corresponded with Sax Rohmer, P.G. Wodehouse, John Creasey and countless other authors.

It was pure pleasure to read his commentary or listen to his conversation. We started corresponding in the late Sixties, thanks mainly to Al Hubin and The Armchair Detective, and met for the first time in 1970 when I took a bus from New Jersey to a science fiction convention in Manhattan that he was attending.

Beginning in 1980 he followed in Keeler’s footsteps by putting out the pre-computer equivalent of a blog, which he called Contact Is Not a Verb (a famous line from one of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novels) and kept going until September 2006, a grand total of 149 issues, of a copy of every one of which I am a proud possessor.

Bob developed diabetes and in the fall of 1990, when I was a visiting professor in New Jersey, had to have some of his toes amputated. Unable to climb the stairs of his own house, he was sleeping in a hospital bed installed on the ground floor. I traveled to Salem by Amtrak and spent a long weekend playing housekeeper: schlepping cartons around so he could access the classical music he loved, taking his clothes to the laundry, even cooking us a few meals (for whose quality I will not vouch).

Until a few years ago we would rendezvous every summer at the Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio. Then unaccountably this shy but gregarious man dropped out of sight. Almost no one heard a word from him or knew anything about his health.

Finally, just a few days before Christmas, I learned he’d been found dead in his house late in November. He had no immediate family. As of this writing I don’t know the cause, or what will happen to the vast library he had accumulated over the decades. All I know is that he was one of the most brilliant and memorable people in my life.

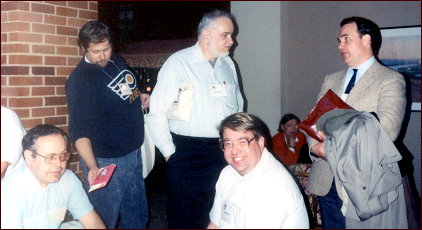

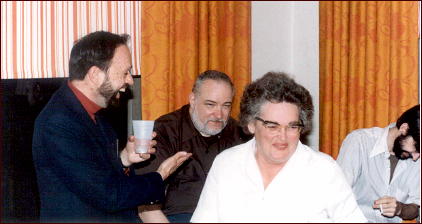

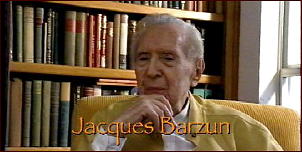

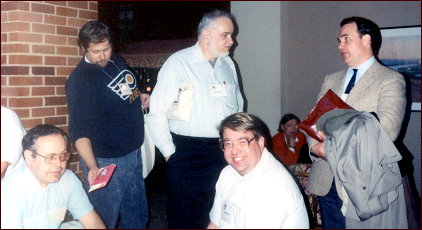

Bouchercon, Philadelphia, 1989. Me (Steve Lewis), Art Scott, Bob Briney, George Kelley, and Mike Nevins. Photo taken by Ellen Nehr.

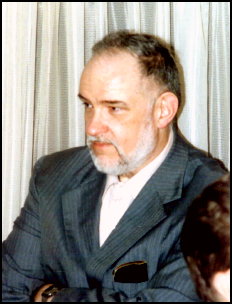

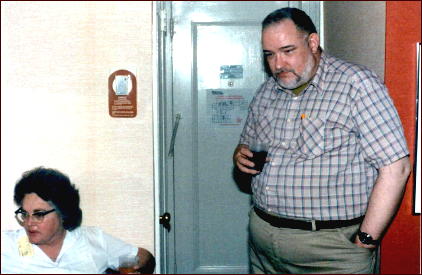

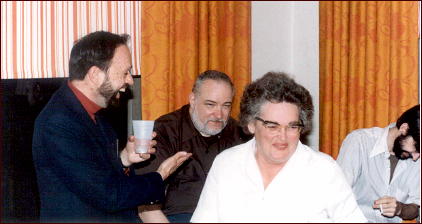

Bouchercon, New York, 1983. Ellen Nehr and Bob Briney.

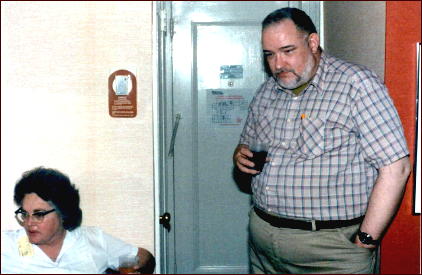

Bouchercon, Chicago, 1984. Marv Lachman, Bob Briney, Ellen Nehr and Steve Stilwell.

Many thanks to Art Scott for providing the photos above.