FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

At the name of Lee Thayer, most mystery fans draw a blank, but in other quarters it’s still well remembered. Emma Redington Lee was born in Troy, Pa. on April 5, 1874, studied at New York City’s Cooper Union and Pratt Institute, and got a job as an interior decorator (which in those days meant a painter of murals for the homes of the wealthy) at New York’s Associated Artists in 1890.

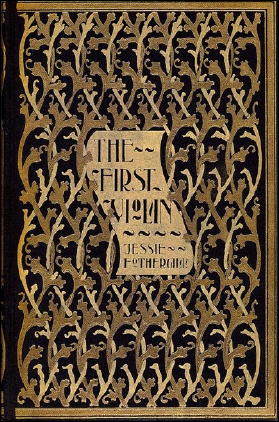

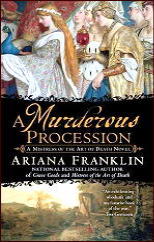

Some of her work was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 when she was still in her teens. Two years later she and Brooklyn architect Henry W. Thayer co-founded Decorative Designers, a firm which in the days before dust jackets produced binding designs, interior illustrations and the like for various New York book publishers. [An example of her work can be found at the end of this post.]

Lee and Thayer were married in 1909. The female partner is credited with having invented a method of using a split ink roller for printing color gradations on book bindings. Decorative Designs was first based in New York but migrated to Chatham, N.J. in 1921 and was dissolved, along with the partners’ marriage, eleven years later. Henry Thayer’s ex-wife called herself Lee Thayer for the rest of her life, probably because it was the byline on her detective novels.

Her first whodunit, The Mystery of the Thirteenth Floor, was published in 1919, when she was 45, and she continued turning out one or two books a year for well over four decades, a total of 61 titles.

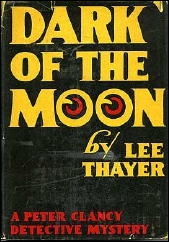

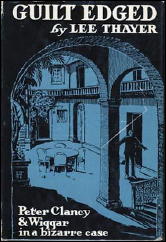

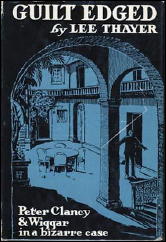

All but one of them featured debonair red-thatched private sleuth Peter Clancy, who in Dead Man’s Shoes (1929) was joined by the intolerable imperturbable Wiggar, a Jeeves clone with an endless supply of scintillating bons mots like “Oh, Mr. Peter, sir!â€.

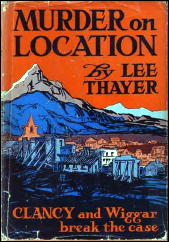

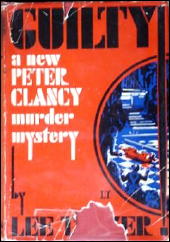

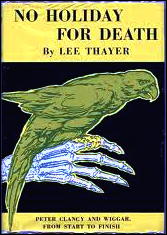

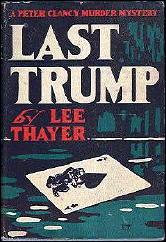

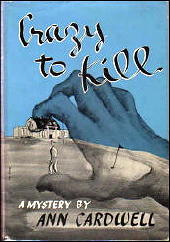

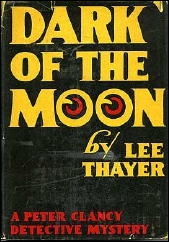

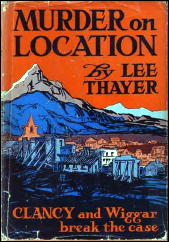

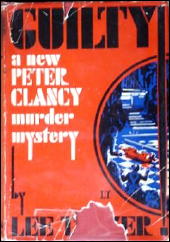

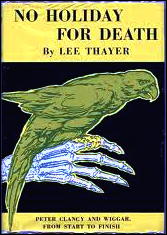

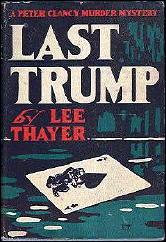

The union between master and valet lasted much longer than many marriages including Thayer’s own. She always thought of writing as a sort of sideline and kept her hand in as an artist by designing the dust jackets for all but the last three of her novels, several examples of which can be seen illustrating this column.

That she never became a household name is demonstrated by her only TV appearance. What’s My Line? was a popular CBS game show whose regular panelists (Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen and Bennett Cerf) were challenged to guess the occupations of various guests.

At the time of her appearance, May 11, 1958, she was 84 years old. Subsequently the program used her photograph in promotional ads: “This sweet little elderly lady writes blood-curdling murder mysteries!†Her last novel, Dusty Death, came out in 1966 when she was 92.

I know nothing about book design, but Thayer still seems to be highly regarded in that field. More than two dozen boxes of her Decorative Designs work are archived at UCLA, along with interviews taped very late in her life in which she reminisced about the firm’s work.

As a mystery writer she’s almost completely forgotten, and perhaps that’s the way it should be, because by ordinary standards there’s very little to recommend her. Feeble plots, clumsy writing, laughable characterizations, elephantine pace, zero fairness to the reader: you name the fault and Thayer’s books have it in spades.

Maybe it’s for this reason that I find in her what novelist and playwright Ira Levin told me he found in John Rhode: the perfect writer to take to bed. (Get that filthy thought out of your minds this instant!) But there are certain recurring elements in her novels that come close to qualifying her as an auteur.

One of these is the apocalyptic denouement. Whenever Peter Clancy has solved a murder to his own satisfaction but has no evidence that will stand up in court, God himself steps into the breach, striking the killer down from on high, while Thayer’s rhetoric swirls and squalls around and kicks up a furious storm.

In Accessory After the Fact (1943) it’s the founder of a quack religious cult who gets the treatment. The same furious deity strikes down totally secular villains in Out, Brief Candle! (1948) and Still No Answer (1958) and in who knows (I almost wrote God knows) how many Thayer novels I’ve never read.

Another Thayer hallmark is the off-the-wall crime method. Ransom Racket (1938) climaxes with Clancy’s reconstruction of a child-kidnapping: the gangsters drove a steam shovel up to the house, aligned the scoop with the baby’s upstairs bedroom window, stuffed the kid in the scoop and drove off undetected. (This is the book where Thayer writes “It was as dark as the inside of a cow†with a perfectly straight face.)

In Accident, Manslaughter or Murder? (1945) the victim is skating across a frozen lake on a moonless night, followed by the murderer in an iceboat which apparently makes no noise. Murderer maneuvers boat behind victim, swats him across the butt with an oar and propels him into a thin patch where the poor schmuck breaks through and drowns.

The novel I chose to concentrate on in my Thayer entry for 1001 Midnights was Out, Brief Candle!, which like Christie’s Death in the Air (1935) is about a murder on an airliner in flight.

It’s twice as long as it need have been, but the solution is passably clever, and I considered this the best Thayer I had read up to the time I wrote the entry. Later I discovered a copy of Evil Root (1949), which brings Clancy to a luxurious retirement home with stiff and unrefundable entrance fees and a suspiciously high death rate among recent residents. This was mystery writer/critic Jon L. Breen’s favorite Thayer, and after I’d read it I found I had to agree with him.

The Second Bullet (1934) has always had a special cachet for me because it’s set in the mountains of northern New Jersey, the state where I grew up. Thayer sets the scene as only she can: “[T]he strong autumn sun warmed the hollows with mists of purple and gold. The color of the woods sang like a great organ. The sky was that thrilling cobalt that seems as if it must be fragrant. Great clouds piled into the zenith. The air was warm and full-flavored like … claret properly unchilled.â€

An auto mishap brings Clancy and Wiggar to the remote mansion of a famous “psychic-analyst†where they discover that he seems to have shot himself to death shortly before their arrival. Concluding that the local cops are idiots who know nothing about detective work and speak in Texas cracker accents to boot (“Meet Captain Tom Joyce, inspector for this here countyâ€), Clancy decides to conceal crucial evidence, invite himself and Wiggar as house guests and stay on to investigate what he has quickly concluded is murder.

In due course he exposes yet another off-the-wall crime method. The murderer and an accomplice drove up to the victim’s isolated house in a utility truck with a long ladder. When the ladder was aligned with the victim’s second-story window, the killer climbed it and, like a demented Paladin, challenged the guy inside to a gun duel!

After twenty years as a northern Californian and resident of Berkeley, Thayer moved to the southern tip of the state and was living with relatives in Coronado in the fall of 1970 when she was interviewed by Jon Breen. At 96, Jon reported, she was still in relatively decent health and able to read with the aid of a combination lamp and magnifying glass.

She was extremely modest about her many mystery novels, saying only that “some are worse than others.†A year or so later there was an exhibition of some of her artwork at the UCLA library. She died on November 18, 1973, just a few months short of her 100th birthday.

The First Violin, by Jessie Fothergill, 1896. Cover design attributed to Lee Thayer.