Tue 13 Jul 2010

A Review by Curt Evans: SAPPER [H. C. MacNEILE] – Knock-Out.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Reviews[16] Comments

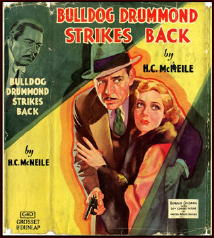

SAPPER [H. C. McNEILE] – Knock-Out. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1933. US title: Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back. Doubleday Doran/Crime Club, hardcover, 1933. Reprints: Grosset & Dunlap, hc, 1934; Triangle, hc, 1943; House of Stratus, UK, trade paperback, 2001.

Films: United Artists, 1934, as Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back (Ronald Colman, Loretta Young; director: Roy del Ruth). Also: Columbia, 1947, again as Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back (Ron Randell, Gloria Henry; director: Frank McDonald).

English thriller writer Sapper (pen name of Herman Cyril McNeile) is a much maligned figure of late decades, his famous hero Captain Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond now being seen as less a “clubland hero” than an arch-conservative, racist, public-schooled bully.

This perception is fueled especially by offensive racial comments made by Captain Drummond in some of the 1920s novels, like The Black Gang (1922) and The Female of the Species (1928). Eric Ambler represented the views of many in dismissing Sapper’s books as essentially fascist.

By 1933, however, Hitler was consolidating his power in Germany and shocking much of the civilized world with his bellicose, frequently anti-Semitic, rhetoric and behavior. Sapper continued publishing thrillers up until his premature death in 1937. What was the tenor of his later works?

My conclusion from reading Knock-Out (1933) is that if you are offended by it, you are pretty easily offended.

Knock-Out opens with Ronald Standish (familiar to Sapper readers from the Sherlock Holmes inspired pastiches he appeared in throughout the 1930s — they should have been collected under the title Knock-Off) and his friend Bill in Ronald’s flat discussing a vital matter — golf — when a phone call from Ronald’s friend Sanderson comes through asking Ronald to come over to his place immediately.

But the line goes dead! Ronald and Bill head over to Sanderson’s place, only to discover Sanderson dead, stabbed — or shot? — through the eye.

They then encounter Hugh Drummond and his friend Peter. The mighty Hugh is about to pound Ronald and Bill into the floor when Peter stops him with an important piece of information: “It’s Ronald Standish. I’ve played cricket with him.”

Ronald’s bona fides as a sportsman established, the four good fellows are able to come together on a plan over what to do about Sanderson’s murder. It seems that Sanderson was on the trail of some sort of BIG criminal conspiracy.

Of course, letting the police or intelligence service in on the “show” in any big way is unthinkable — this is a job for impetuous, sporting, public-schooled amateurs!

Soon Hugh, Ronald and pals are on the hunt for the conspirators, who include a noted society doctor, a sadistic American film actress and, worst of all, a cross-dressing, bald-headed Greek man with lacquered fingernails.

A number of elements from earlier tales are recycled. Hugh again indulges his odd penchant for disguise, his Wodehouseian pal Algy is made to take notes of Hugh’s deep thoughts (to what purpose is not evident), there is a loyal “old nurse” of one of the the fellahs on hand when needed and, of course, a pretty, plucky nice girl (Daphne Frensham — “an absolute fizzer”) shows up to help out the lads, as well as to engage in some light romantic banter with Peter (Hugh’s wife presumably is out shopping during this one).

The heroes’ headstrong assault on the villains’ country house headquarters also will seem familiar, as will the fact that it is defended by a fearsome beast (here, a mastiff “the size of a donkey” — young apes were not available this season, evidently).

Hugh also goes into one of his patented berserk rages, splitting open one filthy swine’s head and throwing another off a railway embankment, but they really were rather rotters, I will stipulate (they had committed an act of what we would call terrorism today and were in the process of attempting another one).

Yet not all is pure action. The presence of the relatively cerebral Ronald Standish gives Sapper an excuse to indulge a little in the exercise of a bit of brain power. There is much speculation over exactly how Sanderson was killed and there is a cipher that plays a major role in the tale.

However, during the course of the action Standish is drugged, kidnapped, kidnapped yet again and concussed by a bomb, so let us just say that his brains are not always fully operational throughout the tale.

Perhaps most interestingly, Sapper takes time to present, in a quite sympathetic manner, a Jewish shopkeeper named Samuel Aaronstein, alone with his wife and son. If Knock-Out ever was reprinted in Nazi Germany — and we know Hitler liked Edgar Wallace thrillers — this section of the book would not have found favor.

It should be noted as well that the sadistic American film actress who is aroused by seeing men being tortured to death is not exactly a cozy concoction. I could never quite figure out why she was necessary to the success of the conspiracy, but she certainly added a frisson of wicked decadence.

So, while Knock-Out is not perhaps the most original of Sapper’s thrillers, it is as smoothly competent as any of the author’s books, and it is not as offensive as people will tell you Sapper works invariably are.

Sure, the lower class characters all speak exaggerated cockney-ish dialect, the street boy with the message for our heroes is invariably referred to by them as “the urchin” (I was half expecting “ragamuffin”) and the head villain is a creepy hermaphrodite (or something like). But, honestly, you must have read more obnoxious books than this one from the period.

I suspect part of the animus against Sapper has to do with the fact that the academics who write much of the mystery criticism today are precisely the eggheads who would have been made to eat dirt three times a day in public school by a young Bulldog (and don’t we know it). Though, admittedly, I too find some of the earlier books distasteful in parts.

Interestingly, Sapper’s father, Captain Malcolm McNeile (1843-1901), was a naval officer and prison warden described as “a ‘rod-of-iron’ officer from the old school” and “a disciplinarian of the meanest type.” And Sapper’s paternal grandfather, Reverend Hugh McNeile (1795-1879) [FOOTNOTE], was an evangelical Anglican minister considered “unquestionably the greatest preacher and speaker in the Church of England” in the nineteenth century.

With this background, it’s probably no wonder that the Sapper books are as conservative (and sometimes bullying) as they are. Whether they are “fascist” — with all that that ideology entails — is to my mind open to question, however.

Conservative and fascist are not synonymous terms. Sapper’s clubland heroes may be vigilantes doing what they do “for the good of England” (which usually seems to mean people earning income off invested capital), but they often seem to find it unnecessary to inform the State what they are doing.

Fascist dictators might have found them a little too anarchic and individualistic in that respect.

FOOTNOTE: Reverend Hugh McNeile obtained his first living in 1822 from the wealthy banker and politician Henry Drummond. Put those names together and I think that we surely have the inspiration for the name of Sapper’s greatest hero.

Previously reviewed on this blog:

The Black Gang (by David L. Vineyard)

Bulldog Drummond (by Steve Lewis)